History of medicine in the United States

These interpretations of medicine vary from early folk remedies that fell under various different medical systems to the increasingly standardized and professional managed care of modern biomedicine.

At the time settlers first came to the United States, the predominant medical system was humoral theory, or the idea that diseases are caused by an imbalance of bodily fluids.

[2] However, as settlers were faced with new diseases and a scarcity of typical plants and herbs used to make therapies in England, they increasingly turned to local flora and Native American remedies as alternatives to European medicine.

[3] This inclusion of a different spiritual system was denounced by Europeans, in particular Spanish colonies, as part of the religious fervor associated with the Inquisition.

Any Native American medical information that did not agree with humoral theory was deemed heretical by Spanish authorities, and tribal healers were condemned as witches.

[8] There was a fundamental difference in the human infectious diseases present in the indigenous peoples and that of sailors and explorers from Europe and Africa.

The indigenous people lacked genetic resistance to such new infections, and suffered overwhelming mortality when exposed to smallpox, measles, malaria, tuberculosis and other diseases.

In the 18th century, 117 Americans from wealthy families had graduated in medicine in Edinburgh, Scotland, but most physicians learned as apprentices in the colonies.

The most famous of the eclectics was Samuel Thomson (1769-1843), a self educated New England farm boy who developed a wildly popular herbal medical system.

Disease was a matter of maladjustment in the body's internal heat, and could be cured by applying certain herbs and medicinal plants, coupled with vomiting, enemas, and steam baths.

Thomson died in 1843, many patients grew worse after the treatment, while a bitter schism emerged among the Thomsonian agents.

Many herbs he popularized, such as cayenne pepper, lobelia, and goldenseal, remain widely used to this day in herbal healing routines.

The Thomsonians had been briefly successful in blocking state laws limited medical practice to licensed physicians.

[26] The war had a dramatic long-term impact on American medicine, from new surgical technique to creation of many hospitals, to expanded nursing and to modern research facilities.

The risk was highest at the beginning of the war when men who had seldom been far from home were brought together for training alongside thousands of strangers who carried unfamiliar germs.

[36] Numerous other new agencies also targeted the medical and morale needs of soldiers, including the United States Christian Commission as well as smaller private agencies such as the Women's Central Association of Relief for Sick and Wounded in the Army (WCAR) founded in 1861 by Henry Whitney Bellows, and Dorothea Dix.

Frederick Law Olmsted, a famous landscape architect, was the highly efficient executive director of the Sanitary Commission.

Following the unexpected carnage at the battle of Shiloh in April 1862, the Ohio state government sent 3 steamboats to the scene as floating hospitals with doctors, nurses and medical supplies.

Billings figured out how to mechanically analyze medical and demographic data by turning information into numbers and punching onto cardboard cards as developed by his assistant Herman Hollerith.

She established nursing training programs in the United States and Japan, and created the first system for keeping individual medical records for hospitalized patients.

[41] Historian Elaine G. Breslaw describes earlier post-colonial American medical schools as "diploma mills", and credits the large 1889 endowment of Johns Hopkins Hospital for giving it the ability to lead the transition to science-based medicine.

The professionalization of medicine, starting slowly in the early 19th century, included systematic efforts to minimize the role of untrained uncertified women and keep them out of new institutions such as hospitals and medical schools.

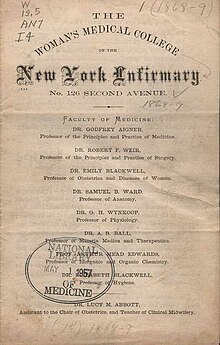

[50]In 1849 Elizabeth Blackwell (1821–1910), an immigrant from England, graduated from Geneva Medical College in New York at the head of her class and thus became the first female doctor in America.

[51] Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, while a younger pioneer Mary Putnam Jacobi (1842-1906) focused on curing disease.

[53] Nursing became professionalized in the late 19th century, opening a new middle-class career for talented young women of all social backgrounds.