Elizabeth Blackwell

Blackwell's interest in medicine was sparked after a friend fell ill and remarked that, had a female doctor cared for her, she might not have suffered so much.

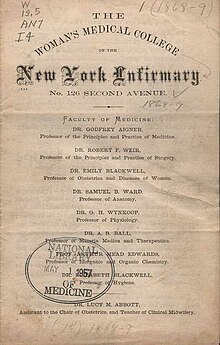

[6] She played a significant role during the American Civil War by organizing nurses, and the Infirmary developed a medical school program for women, providing substantial work with patients (clinical education).

Pressed by financial need, the sisters Anna, Marian and Elizabeth started a school, The Cincinnati English and French Academy for Young Ladies, which provided instruction in most, if not all, subjects and charged for tuition and room and board.

[7] In December 1838, Blackwell converted to Episcopalianism, probably due to her sister Anna's influence, becoming an active member of St. Paul's Episcopal Church.

In the early 1840s, she began to articulate thoughts about women's rights in her diaries and letters and participated in the Harrison political campaign of 1840.

[11] Once again, through her sister Anna, Blackwell procured a job, this time teaching music at an academy in Asheville, North Carolina, with the goal of saving the $3,000 necessary for her medical school expenses.

As to the opinion of people, I don't care one straw personally; though I take so much pains, as a matter of policy, to propitiate it, and shall always strive to do so; for I see continually how the highest good is eclipsed by the violent or disagreeable forms which contain it.

The dean and faculty, usually responsible for evaluating an applicant for matriculation, initially were unable to make a decision due to Blackwell's gender.

In the summer between her two terms at Geneva, she returned to Philadelphia, stayed with Elder, and applied for medical positions in the area to gain clinical experience.

Blackwell slowly gained acceptance at Blockley, although some young resident physicians still refused to assist her in diagnosing and treating her patients.

During her time there, Blackwell gained valuable clinical experience, but was appalled by the syphilitic ward and the condition of typhus patients.

[15][16][17] The local press reported her graduation favorably, and when the dean, Charles Lee, conferred her degree, he stood up and bowed to her.

[11] On 4 November 1849, when Blackwell was treating an infant with ophthalmia neonatorum, she accidentally squirted some contaminated fluid into her own eye and contracted the infection.

[7] Feeling that the prejudice against women in medicine was not as strong in the United States, Blackwell returned to New York City in 1851 with the hope of establishing her own practice.

She also began mentoring Marie Zakrzewska, a Polish woman pursuing a medical education, serving as her preceptor in her pre-medical studies.

[7] When the American Civil War broke out, the Blackwell sisters aided in nursing efforts on the side of the Union Army.

[7] In 1874, Blackwell established a women's medical school in London with Sophia Jex-Blake, who had been a student at the New York Infirmary years earlier.

[7] While Blackwell viewed medicine as a means for social and moral reform, her student Mary Putnam Jacobi focused on curing disease.

She may have perceived herself as a wealthy gentlewoman who had the leisure to dabble in reform and in intellectual activities, being financially supported by the income from her American investments.

[7] Blackwell believed that the Christian morality ought to play as large a role as scientific inquiry in medicine and that medical schools ought to instruct students in the subject.

[29] Others of her time believed women to have little if any sexual passion, and placed the responsibility of moral policing squarely on the shoulders of the woman.

She exchanged letters with Lady Byron about women's rights issues and became very close friends with Florence Nightingale, with whom she discussed opening and running a hospital.

[31] Blackwell also had strained relationships with her sisters Anna and Emily, and with the women physicians she mentored after they established themselves (Marie Zakrzewska, Sophia Jex-Blake and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson).

[7] In 1856, when Blackwell was establishing the New York Infirmary, she adopted Katherine "Kitty" Barry (1848–1936), an Irish orphan from the House of Refuge on Randall's Island.

She even instructed Barry in gymnastics as a trial for the theories outlined in her publication, The Laws of Life with Special Reference to the Physical Education of Girls.

[7] When commenting on a young men trying to court her during her time in Kentucky, she said: "...do not imagine I am going to make myself a whole just at present; the fact is I cannot find my other half here, but only about a sixth, which would not do.

[7] In 1907, while holidaying in Kilmun, Scotland, Blackwell fell down a flight of stairs, and was left almost completely mentally and physically disabled.

Her ashes were buried in the graveyard of St Munn's Parish Church, Kilmun, and obituaries honouring her appeared in publications such as The Lancet[37] and The British Medical Journal.

[46] The National Holiday pays tribute to Blackwell of the role she has played influencing women physicians in present-day and their strive for equity and equality.

[51] Poet Jessy Randall's interest in Blackwell was the original inspiration for what became her 2022 collection of poems about women scientists, Mathematics for Ladies.