History of patent law

In 500 BCE, in the Greek city of Sybaris (located in what is now southern Italy), "encouragement was held out to all who should discover any new refinement in luxury, the profits arising from which were secured to the inventor by patent for the space of a year.

"[2] Athenaeus, writing in the third century CE, cites Phylarchus in saying that in Sybaris exclusive rights were granted for one year to creators of unique culinary dishes.

Another early example of such letters patent was a grant by Henry VI in 1449 to John of Utynam, a Flemish man, for a twenty-year monopoly for his invention.

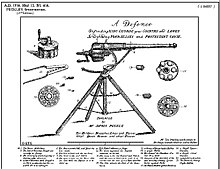

[7][8] Specifically, the well-known Florentine architect received a three-year patent for a barge with hoisting gear, that carried marble along the Arno River.

[9] Patents were systematically granted in Venice as of 1450, where they issued a decree by which new and inventive devices had to be communicated to the Republic in order to obtain legal protection against potential infringers.

[14] By the 16th century, the English Crown would habitually grant letters patent for monopolies to favoured persons (or people who were prepared to pay for them).

This was incorporated into the 1624 Statute of Monopolies in which Parliament restricted the Crown's power explicitly so that the King could only issue letters patent to the inventors or introducers of original inventions for a fixed number of years.

During the reign of Queen Anne, patent applications were required to supply a complete specification of the principles of operation of the invention for public access.

In 1641, Samuel Winslow was granted the first patent in North America by the Massachusetts General Court for a new process for making potash salt.

[19] Towards the end of the 18th century, and influenced by the philosophy of John Locke, the granting of patents began to be viewed as a form of intellectual property right, rather than simply the obtaining of economic privilege.

A notable example of this was the behaviour of Boulton & Watt in hounding their competitors such as Richard Trevithick through the courts, and preventing their improvements to the steam engine from being realised until their patent expired.

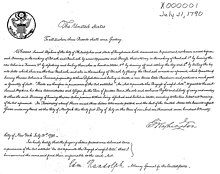

[25] By the end of the 19th century, codified patent laws were enacted in several Western countries, including England (1718), the United States (1790), France (1791), Russia (1814), and Germany (1877), as well as in India (1859) and in Japan (1885).

[34] Its most prominent activists – Isambard Kingdom Brunel, William Robert Grove, William Armstrong and Robert A. MacFie – were inventors and entrepreneurs, and it was also supported by radical laissez-faire economists (The Economist published anti-patent views), law scholars, scientists (who were concerned that patents were obstructing research) and manufacturers.

[35] Johns summarizes some of their main arguments as follows:[36] Similar debates took place during that time in other European countries such as France, Prussia, Switzerland and the Netherlands.

This simplified procedure for obtaining patents, reduced fees and created one office for the entire United Kingdom, instead of different systems for England and Wales and Scotland.