History of copyright

[3] In Greek society, during the sixth century B.C.E., there emerged the notion of the individual self, including personal ideals, ambition, and creativity.

During the Roman Empire, a period of prosperous book trade, no copyright or similar regulations existed,[6] and copying by those other than professional booksellers was rare.

[7] After copyright law became established (in 1710 in England, and in the 1840s in German-speaking areas) the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer, more expensive editions were published.

[7][9] Heinrich Heine, in a 1854 letter to his publisher, complains: "Due to the tremendously high prices you have established, I will hardly see a second edition of the book anytime soon.

"[7] The origin of copyright law in most European countries lies in efforts by the church and governments to regulate and control the output of printers.

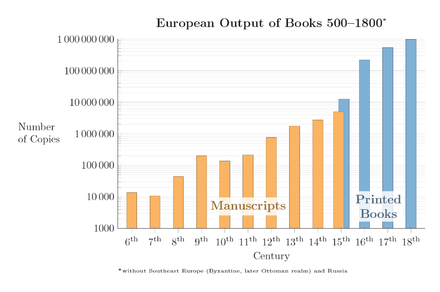

[10] Before the invention of the printing press, a writing, once created, could only be physically multiplied by the highly laborious and error-prone process of manual copying by scribes.

As a consequence, governments established controls over printers across Europe, requiring them to have official licences to trade and produce books.

It was a special case, being the history of the city itself, the Rerum venetarum ab urbe condita opus of Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus.

[12] The second author in the world to achieve copyright, Royal printing privileges, was the humanist and grammarian Antonio de Nebrija, in Lexicon hoc est Dictionarium ex sermone latino in hispaniensem (Salamanca, 1492).

[13] The Republic of Venice, the dukes of Florence, and Leo X and other Popes conceded at different times to certain printers the exclusive privilege of printing for specific terms (rarely exceeding 14 years) editions of classic authors.

[citation needed] The first copyright privilege in England bears date 1518 and was issued to Richard Pynson, King's Printer, the successor to William Caxton.

[14] The earliest German privilege of which there is trustworthy record was issued in 1501 by the Aulic Council to an association entitled the Sodalitas Rhenana Celtica, for the publication of an edition of the dramas of Hroswitha of Gandersheim, which had been prepared for the press by Conrad Celtes .

[16] As the "menace" of printing spread, governments established centralized control mechanisms,[17] and in 1557 the English Crown thought to stem the flow of seditious and heretical books by chartering the Stationers' Company.

The right to print was limited to the members of that guild, and thirty years later the Star Chamber was chartered to curtail the "greate enormities and abuses" of "dyvers contentyous and disorderlye persons professinge the arte or mystere of pryntinge or selling of books."

[17] The notion that the expression of dissent or subversive views should be tolerated, not censured or punished by law, developed alongside the rise of printing and the press.

By defining the scope of freedom of expression and of "harmful" speech Milton argued against the principle of pre-censorship and in favour of tolerance for a wide range of views.

This meant that the Stationers' Company achieved a dominant position over publishing in 17th-century England (no equivalent arrangement formed in Scotland and Ireland).

[20] The Statute of Anne ended the old system whereby only literature that met the censorship standards administered by the booksellers could appear in print.

At the same time, the London booksellers lobbied parliament to extend the copyright term provided by the Statute of Anne.

[22] A debate raged on whether printed ideas could be owned and London booksellers and other supporters of perpetual copyright argued that without it scholarship would cease to exist and that authors would have no incentive to continue creating works of enduring value if they could not bequeath the property rights to their descendants.

Opponents of perpetual copyright argued that it amounted to a monopoly, which inflated the price of books, making them less affordable and therefore prevented the spread of the Enlightenment.

Moreover, he warned, booksellers would then set upon books whatever price they pleased "till the public became as much their slaves, as their own hackney compilers are".

[36] After the French Revolution a dispute over Comédie-Française being granted the exclusive right to the public performance of all dramatic works erupted and in 1791 the National Assembly abolished the privilege.

However, author's rights were subject to the condition of making depositing copies of the work with the Bibliothèque Nationale and 19th-century commentators characterised the 1793 law as utilitarian and "a charitable grant from society".

In 1783 several authors' petitions persuaded the Continental Congress "that nothing is more properly a man's own than the fruit of his study, and that the protection and security of literary property would greatly tend to encourage genius and to promote useful discoveries."

[38] At the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, both James Madison of Virginia and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina submitted proposals that would allow Congress the power to grant copyright for a limited time.

Another important minimum rule established by the Berne Convention is that copyright arises with the creation of a work and does not depend upon any formality such as a system of public registration (Article 5(2)).

The detail of these exceptions was left to national copyright legislation, but the guiding principle is stated in Article 9 of the convention.

The so-called three-step test holds that an exception is only permitted "in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author".

These perspectives may lead to the consideration of alternative compensation systems in place of exclusive rights for all types of information, including software, books, movies, and music.