History of quantum mechanics

The history of quantum chemistry, theoretical basis of chemical structure, reactivity, and bonding, interlaces with the events discussed in this article.

In the final days of the 1800s, J. J. Thomson established that electrons carry a negative charge opposite but the same size as that of a hydrogen ion while having a mass over one thousand times less.

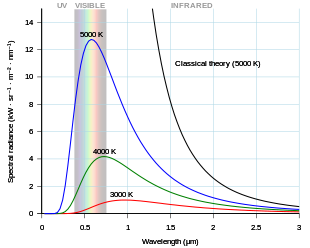

[1]: 365 Throughout the 1800s many studies investigated details in the spectrum of intensity versus frequency for light emitted by flames, by the Sun, or red-hot objects.

Heating it further causes the color to change from red to yellow, white, and blue, as it emits light at increasingly shorter wavelengths (higher frequencies).

In fact, at short wavelengths, classical physics predicted that energy will be emitted by a hot body at an infinite rate.

[10] At the time, however, Planck's view was that quantization was purely a heuristic mathematical construct, rather than (as is now believed) a fundamental change in our understanding of the world.

[1]: I:362 Ten years later, J. J. Thomson showed that the many reports of cathode rays were actually "corpuscles" and they quickly came to be called electrons.

[14] From the introduction section of his March 1905 quantum paper "On a heuristic viewpoint concerning the emission and transformation of light", Einstein states: According to the assumption to be contemplated here, when a light ray is spreading from a point, the energy is not distributed continuously over ever-increasing spaces, but consists of a finite number of "energy quanta" that are localized in points in space, move without dividing, and can be absorbed or generated only as a whole.This statement has been called the most revolutionary sentence written by a physicist of the twentieth century.

[14] Einstein argued that it takes a certain amount of energy, called the work function and denoted by φ, to remove an electron from the metal.

However, it was also known that the atom in this model would be unstable: according to classical theory, orbiting electrons are undergoing centripetal acceleration, and should therefore give off electromagnetic radiation, the loss of energy also causing them to spiral toward the nucleus, colliding with it in a fraction of a second.

By the end of the nineteenth century, a simple rule known as Balmer's formula showed how the frequencies of the different lines related to each other, though without explaining why this was, or making any prediction about the intensities.

[20] Starting from only one simple assumption about the rule that the orbits must obey, the Bohr model was able to relate the observed spectral lines in the emission spectrum of hydrogen to previously known constants.

In Bohr's model, the electron was not allowed to emit energy continuously and crash into the nucleus: once it was in the closest permitted orbit, it was stable forever.

Some fundamental assumptions of the Bohr model were soon proven wrong—but the key result that the discrete lines in emission spectra are due to some property of the electrons in atoms being quantized is correct.

Also, at the Solvay Congress in 1911 Hendrik Lorentz suggested after Einstein's talk on quantum structure that the energy of a rotator be set equal to nhv.

The electron can only exist in certain, discretely separated orbits, labeled by their angular momentum, which is restricted to be an integer multiple of the reduced Planck constant.

The model's key success lay in explaining the Rydberg formula for the spectral emission lines of atomic hydrogen by using the transitions of electrons between orbits.

This implied that the property of the atom that corresponds to the magnet's orientation must be quantized, taking one of two values (either up or down), as opposed to being chosen freely from any angle.

[35]: 56 Spin would generate a tiny magnetic moment that would split the energy levels responsible for spectral lines, in agreement with existing measurements.

Ten months later, Dutch physicists George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit at Leiden University published their theory of electron self rotation.

[1]: 216 De Broglie expanded the Bohr model of the atom by showing that an electron in orbit around a nucleus could be thought of as having wave-like properties.

[39] De Broglie's treatment of the Bohr atom was ultimately unsuccessful, but his hypothesis served as a starting point for Schrödinger's wave equation.

(Alexander Reid, who was Thomson's graduate student, performed the first experiments but he died soon after in a motorcycle accident[40] and is rarely mentioned.)

The first applications of quantum mechanics to physical systems were the algebraic determination of the hydrogen spectrum by Wolfgang Pauli[44] and the treatment of diatomic molecules by Lucy Mensing.

[1]: 275 In 1925, Werner Heisenberg attempted to solve one of the problems that the Bohr model left unanswered, explaining the intensities of the different lines in the hydrogen emission spectrum.

Heisenberg formulated an early version of the uncertainty principle in 1927, analyzing a thought experiment where one attempts to measure an electron's position and momentum simultaneously.

However, Heisenberg did not give precise mathematical definitions of what the "uncertainty" in these measurements meant, a step that would be taken soon after by Earle Hesse Kennard, Wolfgang Pauli, and Hermann Weyl.

[47][48] In the first half of 1926, building on de Broglie's hypothesis, Erwin Schrödinger developed the equation that describes the behavior of a quantum-mechanical wave.

The field of quantum chemistry was pioneered by physicists Walter Heitler and Fritz London, who published a study of the covalent bond of the hydrogen molecule in 1927.

During the same period, Hungarian polymath John von Neumann formulated the rigorous mathematical basis for quantum mechanics as the theory of linear operators on Hilbert spaces, as described in his likewise famous 1932 textbook.