History of tariffs in Australia

Economic historians generally agree that these tariffs were intended to provide employment for miners who had become surplus after the end of the Victorian gold rush.

However, a recent study found no statistically significant evidence that Victoria's embrace of protectionism in the 1860s had any effect on its manufacturing sector.

[2] All colonies, except New South Wales, followed Victoria in adopting tariffs for protective purposes rather than to raise revenue.

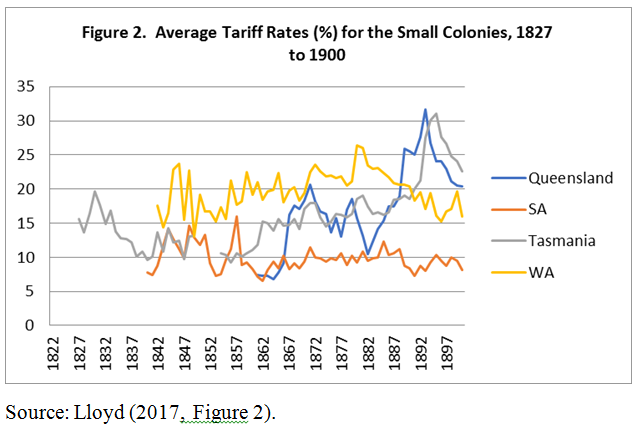

As the range of goods subject to import taxation broadened, the average levels of duty, in ad valorem terms, showed increasing divergence among the colonies.

New South Wales continued an explicit policy of limiting import duties to a small range of goods for revenue purposes (with the notable exception of sugar which was heavily protected).

By the end of the century, Queensland and Western Australia had average rates which were more than double that of Victoria but revenue motives predominated in these colonies.

In the same year the first majority Labour Government was formed, and both parliamentary parties proclaimed their support for protectionism and higher tariffs.

Tariffs stayed at very high levels, with the average rate on dutiable imports only remaining over 40% until after World War II.

This was the first across-the-board tariff cut ever in Australia, although the policy motive was to reduce the rate of inflation, not to improve the efficiency of production.

[12][13][14] A new strategy of gradual phased reductions in tariff rates was introduced by the Hawke Labor government in the 1988 Economic Statement to the House of Representatives.

Since 1921 all changes to substantive tariff rate on individual items or product groups have been subject to review and recommendation by an independent advisory commission or panel.

Because of the high frequency of tariff changes in Australia, this has meant that the statutory authorities have conducted multiple enquiries into some product groups.

The first is multilateral tariff changes (and other policies relating to our commitments as a member of the GATT and later the WTO) and the second is bilateral or regional trade agreements.

It was criticized by the Brigden Committee Report for its lack of an overall view of tariff policy, including its failure to develop a maximum rate of protection.

From the 1960s onwards the Tariff Board became increasingly critical of the high and widely varying levels of protection of manufacturing industries.

This precipitated an intense tussle between the reformist views of the Tariff Board, led by Alf Rattigan, on the one hand and the Whitlam (Labor) and Fraser (Liberal/Country Party) governments on the other.

The Tariff Board began calculating effective rates of industries in the manufacturing sector in its Annual Report for 1968/1969, soon after the concept was invented.

Alf Rattigan, the first chairman of the Industries Assistance Commission, also enthusiastically supported the development of computable general equilibrium modelling (CGE) in Australia to analyze the effects of tariffs.

Since most intermediate inputs have entered duty-free throughout the Commonwealth period, the direct price effects of tariffs are borne mostly by consumers of the products.

A report by the Industries Assistance Commission in 1980 showed that, at that time, the consumer tax effect of tariffs is regressive, falling more heavily on lower income groups.

The Brigden Committee in 1929 predicted that tariffs would induce an overall income redistribution in favor of labor but the later CGE studies do not find this to be true.

The pattern of tariffs and industry protection in Australia has favored manufacturers over the other two sectors producing tradeable goods: agriculture and mining.

"[20] From around the time of the Brigden Committee Report, the farm lobby has sought to offset the bias by increasing assistance to farmers, a policy that was known in the 1920s and 1930s as "protection all round" or, in the 1970s, as "tariff compensation".

The bias holds for every year of the century and it is most strong for the major agricultural exporters – wool, beef, mutton and lamb, and wheat and oats.

The most important group of preferences introduced in Australia are preferential rates derived from the formation of reciprocal regional trade agreements.

Imperial preferences were an important feature of the Australian tariff regime in the 1930s and early post-World War II period.

These preferences have contributed significantly to the lowering of average tariff rates since 1983 though this effect has been limited by some restrictive rules of origin.

However, they have been applied most of the time to industries which already have above-average levels of (nominal and effective) protection, and the implicit ad valorem rates of contingent duty are generally high.

[22] As a second example, the Industries Assistance Commission estimated that these temporary quotas on TCF products were equivalent to an ad valorem tax of 40%.

As top-up measures available virtually on demand, they have helped to maintain heavily protected producers whose existence was vulnerable to import competition.