History of the Alabama Cooperative Extension System

Even so, the roots of Cooperative Extension extend as far back as the late 18th century, following the American Revolution, when affluent farmers first began organizing groups to sponsor educational meetings to disseminate useful farming information.

[1]: 28 A milestone in the history of Cooperative Extension occurred in 1862, when Congress passed, and President Abraham Lincoln signed into law, the Morrill Land-Grant College Act, which granted each state 30,000 acres (120 km²) of public land for each of its House and Senate members.

Despite being plagued initially with severe financial problems, the college, which ultimately became Auburn University, was destined to become the first headquarters of a statewide Extension program.

However, so long as the federal funds were distributed "equitably," states could circumvent this anti-discrimination provision by establishing separate institutions for white and black citizens.

[3] Despite the lofty visions and aspirations reflected in both Morrill Acts, the land grant university system showed signs of foundering toward the close of the 19th century.

The emerging colleges faced serious challenges establishing courses of study that appealed to potential students, particularly Southerners, many of whom were dealing with the far more pressing task of reconstructing an agricultural system badly disrupted by wartime conditions.

Duggar, director of the experiment station at API, and other faculty members felt a strong obligation to reach farmers throughout the state in addition to the "young leaders" who had come to Auburn to undertake formal coursework.

[1]: 26–28 An aging college instructor and administrator often is credited with taking a major, if not critical, lead in efforts that eventually culminated in formal Cooperative Extension work.

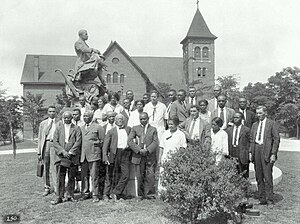

Still held annually, the conference is regarded not only as the cornerstone of black agricultural outreach work but as a major milestone in the development of Cooperative Extension work in general Nevertheless, much like their counterparts at nearby API and in other and other land-grant institutions, Washington and Carver understood that the insights generated at Tuskegee and other agricultural research facilities throughout the nation could not be fully utilized unless they were successfully imparted to farmers.

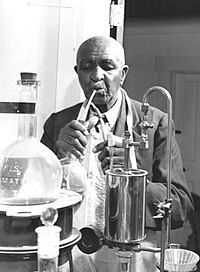

Carver not only drafted the plans for the wagons but also selected the equipment, drew instructional charts and suggested lecture topics to be delivered at each visit.

Thomas Monroe Campbell, of Tuskegee Institute, was appointed the nation's first black extension agent in 1906 and assigned to operate the Jesup wagons under Carver's oversight.

Even before passage of the Smith-Lever Act, Luther Duncan, a 1900 API graduate, had organized numerous Boys' Corn Clubs throughout the state totaling more than 10,000 members in conjunction with his work with the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Plant Industries.

And while he was made a professor of Extension in API's School of Agriculture and selected in the same manner as other faculty members, he was prohibited from teaching regular coursework at the institution.

Duggar, a long-serving API administrator, assumed the reins of the new organization, while Duncan was appointed superintendent of Junior and Home Economics Extension in cooperation with the USDA.

As funds permitted, home demonstration agents were employed to provide farm wives with practical assistance with food preservation and other home-related improvements.

Eventually, program areas were expanded to include assistance with dairying, livestock production, agronomy, horticulture, farm marketing and plant and animal diseases.

Enhanced federal and state funding enabled the Extension Service to hire 11 full-time and part-time subject-matter specialists to provide agents with guidance and assistance with program delivery.

From this comparatively modest beginning, Alabama Extension eventually built a statewide presence with fully staffed and equipped offices in all 67 counties.

[4] After passage of the Smith-Lever Act, plans were put into effect to ensure the rapid growth of what then was known as woman's work, including the number of women agents.

The work was to be targeted specifically to women and their needs rather than indirectly through farm demonstration agents and specialists pursuing the more general goal of improving agricultural and rural conditions.

Already at this early stage, specialists were holding various types of meetings, carrying on extensive correspondence with farmers throughout the state, developing cropping and rotation systems, working out cream-gathering routes and undertaking a campaign for the prevention and restriction of hog cholera.

[4] Eventually, program areas were expanded to include assistance with dairying, livestock production, agronomy, horticulture and plant and animal diseases.

[19] Developing a sound farm marketing strategy for the growing diversity of Alabama-grown products was considered an especially important focus of Alabama Extension's initial efforts.

Enhanced federal and state funding also enabled the Extension Service to hire 11 full-time and part-time subject-matter specialists to provide agents with guidance and assistance with program delivery.

From this comparatively modest beginning, Alabama Extension eventually built a statewide presence with fully staffed and equipped offices in all 67 counties.

Alabama, Davis stressed, was diversifying, moving from a primarily cotton-based economy "into a combination of cotton and other cash crops plus livestock and poultry."

He envisioned a dual purpose for the murals and supporting exhibits: to celebrate Alabama's rich agricultural history but also to focus farmers on a "vision of the future.

By 1925, WAPI, "the Voice of Alabama," a far more powerful station, was broadcasting a 1,000-watt signal from the third floor of Comer Hall on the API (now Auburn University) campus.

Alabama Extension also was an early adopter of web blogs not only as a more efficient way to educate its audiences but also to disseminate breaking news to key media gatekeepers throughout the state.

In Smith's view, this was not surprising, considering that clients increasingly looked to Extension's Web presence "as the most accessible source of information about Extension-related programs and services."