History of the Constitution of Brazil

Drafting of the first Constitution of Brazil was quite difficult and the power struggle involved resulted in a long-lasting unrest that plagued the country for nearly two decades.

In light of the wave of conservatism led by the Holy Alliance, the Emperor used his influence over the Brazilian Army to dissolve the Constitutional Assembly, in what became known as the Night of Agony.

It created executive, legislative, judicial, and moderating branches as "delegations of the nation" with the separation of those powers envisaged as providing balances in support of the Constitution and the rights it enshrined.

The new constitution, published on March 25, 1824 outlined the existence of four powers: The Emperor controlled the Executive by nominating the members of the State Council, influenced the Legislative by being allowed to propose motions and having the power to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies (senators sat for life, however, being individually chosen by the emperor among the top three candidates in a given province) and also influenced the Judiciary, by appointing (for life) the members of the Highest Court.

The Amendment (Ato Adicional) of August 12, 1834, enacted in a period of liberal reform, authorized the provinces to create their own legislative chambers, which were empowered to legislate on financial matters, create taxes and their own corps of civil servants under a chief executive nominated by the central power;[3] it was however revised by an "interpretive" act of May 1840, enacted in a period of conservative reaction, which allowed the central power to appoint judges and police officers in the provinces.

[8] On November 15, 1889, the emperor Pedro II was deposed, Brazilian monarchy abolished and the 1824 Constitution was put out of effect.

The writing process began in 1889, by a group of jurists and politicians, and the text was later amended by a Constitutional Congress on February 24, 1891.

The main traits of the constitution were: In 1930, after severe political problems, President Washington Luís was overthrown by a coup d'état.

As a consequence of this, it incorporated a number of improvements to Brazilian political, social and economical life: On the night of November 10, 1937, Vargas announced in a nationwide radio address that he was seizing emergency powers under the pretext of suppressing a Communist-backed coup (the so-called Cohen Plan).

On the same night, he promulgated a new constitution that effectively transformed his presidency into a legal dictatorship (the short interval suggesting that the self-coup had been planned well in advance).

After the military coup d'état of April 1, 1964 the controllers of the new regime kept the 1946 constitution and promised to restore democracy as soon as possible.

The so-called Institutional Acts sequentially issued by the military presidents were, in practice, placed higher than the Constitution and could amend it.

Even under these circumstances, the first military president, Humberto de Alencar Castelo Branco, was committed to restoring civilian rule in 1966.

The main features of the new Constitution were: In 1969, this already severely authoritarian document was widely amended by a provisional military junta and made even more repressive.

It appears as a reaction to the period of military dictatorship[citation needed], seeking to guarantee all manner of rights and restricting the state's ability to limit freedom, to punish offenses and to regulate individual life.

Consequently, Brazil later approved a law making the propagation of prejudice against any minority or ethnic group an unbailable crime.

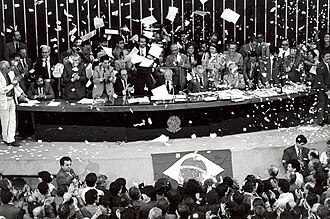

Willing to create a truly democratic state[citation needed], the Constitution has established many forms of direct popular participation besides regular voting, such as plebiscite, referendum and the possibility of ordinary citizens proposing new laws.

The mention of God in the preamble of the Constitution (and later on the Brazilian currency) was opposed by most leftists as incompatible with freedom of religion because it does not recognize the rights of polytheists (like the Amerindians) or atheists, but it has not been removed so far.

Therefore, the preamble which is not actually a part of the supreme law, has no judicial validity whatsoever and cannot impose obligations or create rights.[importance?]