History of the Eastern Orthodox Church

In the Late Middle Ages, the Fall of Constantinople brought a large part of the world's Orthodox Christians under Ottoman Turkish rule.

As the Ottoman Empire declined in the 19th century and several majority-Orthodox nations regained their independence, they organized a number of new autocephalous Orthodox churches in Southern and Eastern Europe.

Early growth also occurred in the two political centers of Rome and Greece, as well as in Byzantium (initially a minor centre under the Metropolitan of Heraclea, but which later became Constantinople).

The church has the rest of the liturgical ritual being rooted in Jewish Passover, Siddur, Seder, and synagogue services, including the singing of hymns (especially the Psalms) and reading from the Scriptures (Old and New Testament).

The oldest complete canon of the Christian Bible was found at Saint Catherine's Monastery (see Codex Sinaiticus) and later sold to the British by the Soviets in 1933.

[9] In the 530s the second Church of the Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) was built in Constantinople under emperor Justinian I, to become the center of the ecclesiastical community for the rulers of the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium.

These doctrinal differences were first openly discussed during the patriarchate of Photius I. Rome interpreted her primacy among the Pentarchy of five sees in terms of sovereignty, as a God-given right involving universal jurisdiction in the Church.

Some churches of the East believed that the Roman See had a primacy of honour but not supremacy, i.e. the Pope being the first among equals, not an absolute authority with the ability to make infallible statements.

[23] The forming of Christianity as state religion dates to the time of the Eastern Orthodox missionaries (Saints) Cyril and Methodius during Basil I (r. 867–886), who baptised the Serbs sometime before helping Knez Mutimir in the war against the Saracens in 869, after acknowledging the suzerainty of the Byzantine Empire.

In a letter to Boris, the Byzantine emperor Michael III expressed his disapproval of Bulgaria's religious reorientation and used offensive language against the Roman Church.

The Roman mission's efforts were met with success and King Boris asked Pope Nicholas I to appoint Formosa of Portua as Bulgarian Archbishop.

In the next 10 years, Pope Adrian II and his successors made desperate attempts to reclaim their influence in Bulgaria, but their efforts ultimately failed.

St. Clement, St. Naum and St. Angelaruis returned to Bulgaria, where they managed to instruct several thousand future Slavonic clergymen in the rites using the Slavic language and the Glagolitic alphabet.

There were doctrinal issues like the filioque clause and the authority of the Pope involved in the split, but these were exacerbated by cultural and linguistic differences between Latins and Greeks.

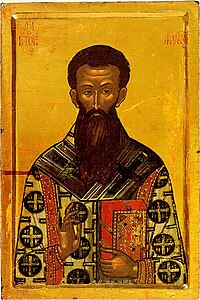

[29] Around the year 1337, Hesychasm attracted the attention of a learned member of the Orthodox Church, Barlaam, a Calabrian monk who at that time held the office of abbot in the Monastery of St Saviour's in Constantinople and who visited Mount Athos.

There, he encountered Hesychasts and heard descriptions of their practices, also reading the writings of the teacher in Hesychasm of St Gregory Palamas, himself an Athonite monk.

On the Hesychast side, the controversy was taken up by Antonite St Gregory Palamas, afterwards Archbishop of Thessalonica, who was asked by his fellow monks on Mt Athos to defend Hesychasm from Barlaam's attacks.

This exodus of highly educated Greek scholars, later reinforced by refugees following the Fall of Constantinople of 1453, had a significant influence on the first generation (that of Petrarca and Boccaccio) of the incipient Italian Renaissance.

[30] The Teutonic Order's failed attempts to conquer Orthodox Russia (particularly the Republics of Pskov and Novgorod), an enterprise endorsed by Pope Gregory IX,[31] can also be considered as a part of the Northern Crusades.

Many Orthodox saw the actions of the Catholics in the Mediterranean as a prime determining factor in the weakening of Byzantium which led to the Empire's eventual conquest and fall to Islam.

Orthodoxy in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Jordan, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan (see Melkite and Kurdish Christians).

[48][49] In the case of anti-semitism and the anti-Jewish pogroms, no evidence is given of the direct participation of the church; many Russian Orthodox clerics, including senior hierarchs, openly defended persecuted Jews, at least starting in the second half of the 19th century.

[50][51][52] In modern times, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn has been accused of antisemitism for his book Two Hundred Years Together, where he alleges Jewish participation in the political repression of the Soviet regime (see also Hebrew and Byzantine relations).

[69] In some other communist states such as Romania, the Eastern Orthodox Church as an organisation enjoyed relative freedom and even prospered, albeit under strict secret police control.

That, however, did not rule out demolishing churches and monasteries as part of broader systematization (urban planning), state persecution of individual believers, and Romania stands out as a country which ran a specialised institution where many Orthodox (along with peoples of other faiths) were subjected to psychological punishment or torture and mind control experimentation in order to force them give up their religious convictions (see Pitești Prison).

The resultant body is known as the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, which maintains close ties with the Orthodox and is holding ongoing talks about healing the schism.

[citation needed] The movement to reestablish communion with the See of Rome within East-Central Europe was started with the 1598–1599 Union of Brest, by which the "Metropolia of Kiev-Halych and all Rus'" entered into relationship with the Roman Catholic Church.

It is feared that this ploy would diminish the power to the original eastern Patriarchs of the church and would require the acceptance of rejected doctrines and Scholasticism over faith.

The members of the holy synod of Antioch continue to explore greater communication and more friendly meetings with their Syriac, Melkite, and Maronite brothers and sisters, who all share a common heritage.

In fact, conditions in the Parthian empire (250 BC – AD 226), which stretched from the Euphrates to the Indus rivers and the Caspian to the Arabian seas, were in some ways more favourable for the growth of the church than in the Roman world.