History of Protestantism

[citation needed] After excommunicating Luther in 1521 with the papal bull Decet Romanum Pontificem, Church leaders together with the Holy Roman Empire condemned his followers in the 1521 Edict of Worms.

Although it was rejected by Charles V, there was no document written in response on the Catholic side, and Luther submitted his 1537 Smalcald Articles for consideration to the German nobility, which he wrote also in the hopes that the impending council would not misrepresent his positions, even if it were just going to condemn them.

[citation needed] While the Counter-Reformation on the continent continued until the 19th century,[a] the growth of a Puritan party dedicated to further Protestant reform polarized the Elizabethan Age, although it was not until the Civil War of the 1640s that England underwent religious strife comparable to that which its neighbours had suffered some generations before.

[citation needed] In the 21st century, Protestantism continues to divide, while simultaneously expanding on a worldwide scale largely due to rising Evangelical Protestant and Pentecostal movements.

In Germany, a hundred years later, protests against Roman Catholic authorities erupted in many places at once during a time of threatened Islamic Ottoman invasion ¹ which distracted the German princes in particular.

These frustrated reformist movements ranged from nominalism, devotio moderna (modern devotion), to humanism occurring in conjunction with economic, political and demographic forces that contributed to a growing disaffection with the wealth and power of the elite clergy, sensitizing the population to the financial and moral corruption of the secular Renaissance church.

In the emerging urban centers, however, the calamities of the fourteenth and early fifteenth century, and the resultant labor shortages, provided a strong impetus for economic diversification and technological innovations.

Following the Black Death, the initial loss of life due to famine, plague, and pestilence contributed to an intensification of capital accumulation in the urban areas, and thus a stimulus to trade, industry, and burgeoning urban growth in fields as diverse as banking (the Fugger banking family in Augsburg and the Medici family of Florence being the most prominent); textiles, armaments, especially stimulated by the Hundred Years' War, and mining of iron ore due, in large part, to the booming armaments industry.

As a direct result of the move toward centralization, leaders like Louis XI of France (1461–1483), the "spider king", sought to remove all constitutional restrictions on the exercise of their authority.

But as recovery and prosperity progressed, enabling the population to reach its former levels in the late 15th and 16th centuries, the combination of a newly-abundant labor supply and improved productivity, was a mixed blessing for many segments of Western European society.

New thinking favored the notion that no religious doctrine can be supported by philosophical arguments, eroding the old alliance between reason and faith of the medieval period laid out by Thomas Aquinas.

The major individualistic reform movements that revolted against medieval scholasticism and the institutions that underpinned it were humanism, devotionalism, (see for example, the Brothers of the Common Life and Jan Standonck) and the observantine tradition.

The polarization of the scholarly community in Germany over the Reuchlin (1455–1522) affair, attacked by the elite clergy for his study of Hebrew and Jewish texts, brought Luther fully in line with the humanist educational reforms who favored academic freedom.

The increasingly well-educated middle sectors of Northern Germany, namely the educated community and city dwellers would turn to Luther's rethinking of religion to conceptualize their discontent according to the cultural medium of the era.

While priests emphasized works of religiosity, the respectability of the church began diminishing, especially among well educated urbanites, and especially considering the recent strings of political humiliation, such as the apprehension of Pope Boniface VIII by Philip IV of France, the "Babylonian Captivity", the Great Schism, and the failure of Conciliar reformism.

In a sense, the campaign by Pope Leo X to raise funds to rebuild St. Peter's Basilica was too much of an excess by the secular Renaissance church, prompting high-pressure indulgences that rendered the clergy establishments even more disliked in the cities.

Following the excommunication of Luther and condemnation of the Reformation by the Pope, the work and writings of John Calvin were influential in establishing a loose consensus among various groups in Switzerland, Scotland, Hungary, Germany and elsewhere.

The compromise was uneasy and was capable of veering between extreme Calvinism on the one hand and Catholicism on the other, but compared to the bloody and chaotic state of affairs in contemporary France, it was relatively successful until the Puritan Revolution or English Civil War in the seventeenth century.

The success of the Counter-Reformation on the Continent and the growth of a Puritan party dedicated to further Protestant reform polarized the Elizabethan Age, although it was not until the 1640s that England underwent religious strife comparable to that which its neighbours had suffered some generations before.

They refused to endorse completely all of the ritual directions and formulas of the Book of Common Prayer; the imposition of its liturgical order by legal force and inspection sharpened Puritanism into an opposition movement.

Beyond the reach of the French kings in Geneva, Calvin continued to take an interest in the religious affairs of his native land including the training of ministers for congregations in France.

The Reformation in the Netherlands, unlike in many other countries, was not initiated by the rulers of the Seventeen Provinces, but instead by multiple popular movements, which in turn were bolstered by the arrival of Protestant refugees from other parts of the continent.

People began to study the Bible at home, which effectively decentralized the means of informing the public on religious manners and was akin to the individualistic trends present in Europe during the Protestant Reformation.

The Second Great Awakening made its way across the frontier territories, fed by intense longing for a prominent place for God in the life of the new nation, a new liberal attitude toward fresh interpretations of the Bible, and a seemingly contagious experience of zeal for authentic spirituality.

In doing so, new critical approaches to the Bible were developed, new attitudes became evident about the role of religion in society, and a new openness to questioning the nearly universally accepted definitions of Christian orthodoxy began to become obvious.

Especially targeting critical approaches to the interpretation of the Bible, and trying to blockade the inroads made into their churches by atheistic scientific assumptions, the fundamentalists began to appear in various denominations as numerous independent movements of resistance to the drift away from historic Christianity.

This branch of thought arose in the early 20th century in the context of the rise of the Third Reich in Germany and the accompanying political and ecclesiastical destabilization of Europe in the years before and during World War II.

Neo-orthodoxy's highly contextual, dialectical modes of argument and reasoning often rendered its main premises incomprehensible to American thinkers and clergy, and it was frequently either dismissed out of hand as unrealistic or cast into the reigning left- or right-wing molds of theologizing.

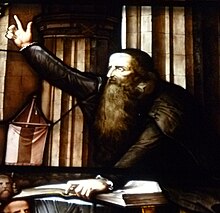

Karl Barth, a Swiss Reformed pastor and professor, brought this movement into being by drawing upon earlier criticisms of established (largely modernist) Protestant thought made by the likes of Søren Kierkegaard and Franz Overbeck.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer, murdered by the Nazis for allegedly taking part in an attempt to overthrow the Hitler regime, adhered to this school of thought; his classic The Cost of Discipleship is likely the best-known and accessible statement of the neo-orthodox position.