Unbuilt plans for the Second Avenue Subway

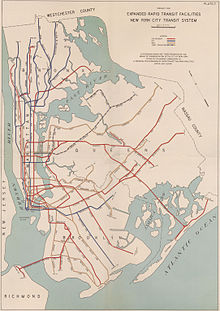

[2][3] Turner's final paper, titled Proposed Comprehensive Rapid Transit System, was a massive plan calling for new routes under almost every north-south Manhattan avenue, extensions to lines in Brooklyn and Queens, and several crossings of the Narrows to Staten Island.

[2][4]: 11–18, map at back cover Massively scaled-down versions of some of Turner's plans were found in proposals for the new city-owned Independent Subway System (IND).

[5] Among the plans was a massive trunk line under Second Avenue consisting of at least six tracks and numerous branches throughout Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx.

[7] On September 16, 1929, the Board of Transportation of the City of New York (BOT) tentatively approved the expansion,[3][5] which included a Second Avenue Line with a projected construction cost of $98,900,000 (equivalent to $1,739,000,000 in 2023), not counting land acquisition.

[15] By 1932, the Board of Transportation had modified the plan to further reduce costs, omitting a branch in the Bronx, and truncating the line's southern terminus to the Nassau Street Loop.

The United States' entry into World War II in 1941 halted all but the most urgent public works projects, delaying the Second Avenue Line once again.

[3][16][18] The demolition of the Second Avenue elevated caused overcrowding on the Astoria and Flushing Lines in Queens, which no longer had direct service to Manhattan's far East Side.

The southern two-track portion was abandoned as a possible future plan for connecting the line to Brooklyn, while a Bronx route to Throggs Neck was put forth.

[6]: 210–211 Under Mayor William O'Dwyer and General Charles P. Gross, another plan was put forth in 1947 by Colonel Sidney H. Bingham, a city planner and former Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) engineer.

[7] The New York Board of Transportation ordered ten new prototype subway cars made of stainless steel from the Budd Company.

Reflecting public health concerns of the day, especially regarding polio, the R11 cars were equipped with electrostatic air filters and ultraviolet lamps in their ventilation systems to kill germs.

[7][10][24] Money from the 1951 bond measure was diverted to buy new cars, lengthen platforms, and maintain other parts of the aging New York City Subway system.

In his 1974 book The Power Broker, Robert A. Caro estimated that this amount of money could modernize both the Long Island Rail Road for $700 million and the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad for $500 million, with money left over to build the Second Avenue Subway as well as proposed extensions of subway lines in Queens and Brooklyn.

This segment, the Chrystie Street Connection, was first proposed in the 1947 plan as the southern end of the Second Avenue line, which would feed into the two bridges.

[32]: 135 Mayor John Lindsay, on August 16, 1970, announced the approval of a $11.6 million design contract for the line, which was awarded to DeLeuw, Cather & Company.

A second branch would connect to the IRT Pelham Line in the vicinity of Whitlock Avenue station, another element from earlier plans.

All stations on the Dyre Avenue and upper Pelham Lines would have platforms shaved back to accommodate larger B Division trains.

[40] All stations would have included escalators, high intensity lighting, improved audio systems, platform edge strips, and non-slip floors to accommodate the needs of the elderly and people with disabilities, but no elevators.

[17]: 107 [42]: 37 The Second Avenue line was criticized as a "rich man's express, circumventing the Lower East Side with its complexes of high-rise low- and middle-income housing and slums in favor of a silk stocking route.”[6]: 218 In order to cut down on walking distance, the stations would have been up to four blocks long.

The plan for stations was reluctantly disclosed by the NYCTA on August 27, 1970 after a meeting with Assemblyman Stephen Hansen, who represented an area that covered the Upper East Side.

[44] In September 1970, MTA Chairman William Ronan promised to host meetings with members of communities along the Second Avenue subway's route.

[43]: 37 The line's planned route on Second Avenue, Chrystie Street and the Bowery in the Lower East Side also drew criticism from citizens and officials.

[48] In January 1970, the MTA issued a plan for a spur line, called the "cuphandle", to serve the heart of the Lower East Side.

When politicians from the Lower East Side started advocating for the $55 million (worth about $414,000,000 in current dollars) Avenue C cuphandle, which would have served nearly 50,000 people, Queens politicians stated that the money would be better used to reactivate the abandoned Rockaway Beach Branch, which would cost only $45 million (equal to about $339,000,000 today) and would serve over 300,000 people.

[63] In spite of the optimistic outlook for the Second Avenue line's construction, the subway had seen a 40% decrease in ridership since 1947, and its decline was symptomatic of the downfall of the city as a whole.

[52] In October 1974, the MTA chairman, David Yunich, announced that the completion of the line north of 42nd Street was pushed back to 1983 and the portion to the south in 1988.

[73] Of this failure to complete construction, Gene Russianoff, an advocate for subway riders since 1981, stated: "It's the most famous thing that's never been built in New York City, so everyone is skeptical and rightly so.

[80] As part of Phase 2, the section originally intended to be occupied by the middle track will instead be utilized for the 116th Street station's island platform.

[11] New York voters passed a transportation bond issue in November 2005, allowing for dedicated funding allocated for phase 1, which was to run from 96th to 63rd Street.

[102]: 9 [105]: 51 Instead the MTA has proposed a deeper tunnel alignment in this area, including a new lower level at Grand Street, to reduce construction impacts on the Chinatown community.