History of the Shroud of Turin

[1] Historical records seem to indicate that a shroud bearing an image of a crucified man existed in the possession of Geoffroy de Charny in the small town of Lirey, France around the years 1353 to 1357.

[6] Barbara Frale has cited that the Order of Knights Templar were in the possession of a relic showing a red, monochromatic image of a bearded man on linen or cotton.

Rinaldi also points out that the alleged shroud in the Pray Codex does not contain any image of a human body, and that a wadded cloth is clearly visible on top of this object.

It is related that the widow of the French knight Geoffroi de Charny had it displayed in a church at Lirey, France (diocese of Troyes).

In 1418 during the civil wars, the canons entrusted the Winding Sheet to Humbert, Count de La Roche, Lord of Lirey.

"[22]In the Museum Cluny in Paris, the coats of arms of this knight and his widow can be seen on a pilgrim medallion, which also shows an image of the Shroud of Turin.

During the fourteenth century, the shroud was often publicly exposed, though not continuously, because the bishop of Troyes, Henri de Poitiers, had prohibited veneration of the image.

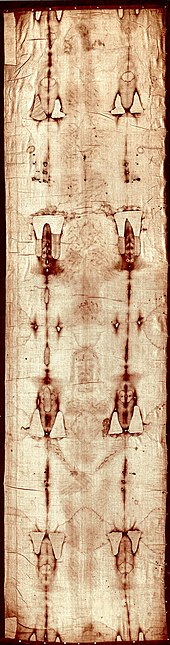

The letter provides an accurate description of the cloth: "upon which by a clever sleight of hand was depicted the twofold image of one man, that is to say, the back and the front, he falsely declaring and pretending that this was the actual shroud in which our Saviour Jesus Christ was enfolded in the tomb, and upon which the whole likeness of the Saviour had remained thus impressed together with the wounds which He bore."

[30] In 1418, Humbert of Villersexel, Count de la Roche, Lord of Saint-Hippolyte-sur-Doubs, moved the shroud to his castle at Montfort, Doubs, to provide protection against criminal bands, after he married Charny's granddaughter Margaret.

The new owner, Anne of Cyprus, Duchess of Savoy, stored it in the Savoyard capital of Chambéry in the newly built Saint-Chapelle, which Pope Paul II shortly thereafter raised to the dignity of a collegiate church.

In 1464, Anne's husband, Louis, Duke of Savoy agreed to pay an annual fee to the Lirey canons in exchange for their dropping claims of ownership of the cloth.

Beginning in 1471, the shroud was moved between many cities of Europe, being housed briefly in Vercelli, Turin, Ivrea, Susa, Chambéry, Avigliana, Rivoli, and Pinerolo.

A description of the cloth by two sacristans of the Sainte-Chapelle from around this time noted that it was stored in a reliquary: "enveloped in a red silk drape, and kept in a case covered with crimson velours, decorated with silver-gilt nails, and locked with a golden key."

In 1543 John Calvin, in his Treatise on Relics, wrote of the Shroud, which was then at Nice, "How is it possible that those sacred historians, who carefully related all the miracles that took place at Christ’s death, should have omitted to mention one so remarkable as the likeness of the body of our Lord remaining on its wrapping sheet?"

In 1988, the Holy See agreed to a radiocarbon dating of the relic, for which a small piece from a corner of the shroud was removed, divided, and sent to laboratories.

[35] Another fire, possibly caused by arson, threatened the shroud on 11 April 1997, but fireman Mario Trematore was able to remove it from its heavily protected display case and prevent further damage.

[36] In 2003, the principal restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, a textile expert from Switzerland, published a book with the title Sindone 2002: L'intervento conservativo – Preservation – Konservierung (ISBN 88-88441-08-5).

[37] Banding on the Shroud is background noise, which causes us to see the gaunt face, long nose, deep eyes, and straight hair.

[40][41] In June 2009, the British television station Channel 5 aired a documentary that claimed the shroud was forged by Leonardo da Vinci.

[42] According to the study, the Renaissance artist created the artifact by using pioneering photographic techniques and a sculpture of his own head, and suggests that the image on the relic is Leonardo's face which could have been projected onto the cloth, The Daily Telegraph reported.

[42] In an article published by History Today in November 2014, British scholar Charles Freeman analyses early depictions and descriptions of the Shroud and argues that the iconography of the bloodstains and all-over scourge marks are not known before 1300 and the Shroud was a painted linen at that date, with the paint having disintegrated leaving a discoloured linen image underneath.