History of the United States dollar

The United States dollar is now the world's primary reserve currency held by governments worldwide for use in international trade.

Made with similar silver content to its counterparts minted in Mexico and Peru, the Spanish, U.S. and Mexican silver dollars all circulated side by side in the United States, and the Spanish dollar and Mexican peso remained legal tender until the Coinage Act of 1857.

[1] Congress appointed Robert Morris to be Superintendent of Finance of the United States following the collapse of the Continental currency.

The Bank of North America was funded in part by bullion coin, loaned to the United States by France.

Subsequently, the American administration of President George Washington turned its attention to monetary issues again in the early 1790s, under the leadership of Alexander Hamilton, the Secretary of the Treasury at the time.

The Mint had the authority to convert any precious metals into standard coinage for anyone's account with no seigniorage charge beyond refining costs.

The discovery of large silver deposits in the Western United States in the late 19th century created a political controversy.

On one side were agrarian interests such as the Greenback Party that wanted to retain the bimetallic standard in order to inflate the dollar, which would allow farmers to more easily repay their debts.

It led to the famous Cross of Gold speech given by William Jennings Bryan, and may have inspired many of the themes in The Wizard of Oz.

Despite the controversy, the status of silver was slowly diminished through a series of legislative changes from 1873 to 1900, when a gold standard was formally adopted.

With debts to Europe falling due, the dollar to (British) pound sterling exchange rate reached as high as $6.75:£1,[when?]

In order to defend the exchange rate of the dollar, the US Treasury Department authorized state and nationally chartered banks to issue emergency currency under the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, and the newly created Federal Reserve organized a fund to assure debts to foreign creditors.

These efforts were largely successful, and the Aldrich-Vreeland notes were retired starting in November and the gold standard was restored when the New York Stock Exchange re-opened in December 1914.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve was forced to raise interest rates in order to protect the gold standard for the US dollar, worsening already severe domestic economic pressures.

[12][15] Under the post-World War II Bretton Woods system, all other currencies were valued in terms of U.S. dollars and were thus indirectly linked to the gold standard.

The need for the U.S. government to maintain both a $35 per troy ounce (112.53 cents/gram) market price of gold and also the conversion to foreign currencies caused economic and trade pressures.

By that time floating exchange rates had also begun to emerge, which indicated the de facto dissolution of the Bretton Woods system.

In the early 1970s, inflation caused by rising prices for imported commodities, especially oil, and spending on the Vietnam War that was not counteracted by cuts in other government expenditures, combined with a trade deficit to create a situation in which the dollar was worth less than the gold used to back it.

[clarification needed] The sudden jump in the price of gold after the demise of the Bretton Woods accords was a result of the significant prior debasement of the US dollar due to excessive inflation of the monetary supply via central bank (Federal Reserve) coordinated fractional reserve banking under the Bretton Woods partial gold standard.

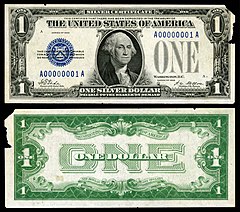

[17] They were produced in response to silver agitation by citizens who were angered by the Fourth Coinage Act, and were used alongside the gold-based dollar notes.

In 1933, Congress passed the Agricultural Adjustment Act which included a clause allowing for the pumping of silver into the market to replace the gold.

[citation needed] Demand Notes are a type of United States paper money issued from August 1861 to April 1862 during the American Civil War in denominations of 5, 10, and 20 US$.

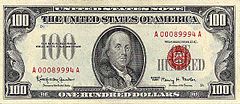

[20] United States Notes were created as fiat currency, in that the government has never categorically guaranteed to redeem them for precious metal - even though at times, such as after the specie resumption of 1879, federal officials were authorized to do so if requested.

In 1944, Allied nations sought to create an international monetary order that sustained the global economy and prevented the economic malaise that followed the First World War.

The international community needed dollars to finance imports from the United States to rebuild what was lost in the war.

[29] Consequently, some proponents of the intrinsic theory of value believe that the near-zero marginal cost of production of the current fiat dollar detracts from its attractiveness as a medium of exchange and store of value because a fiat currency without a marginal cost of production is easier to debase via overproduction and the subsequent inflation of the money supply.

A single bill weighs about fifteen and a half grains (one gram) and costs approximately 4.2 cents for the Bureau of Engraving and Printing to produce.

And to uphold our currency's soundness, it must be recognized and honored as legal tender and counterfeiting must be effectively thwarted," Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan said at a ceremony unveiling the $20 bill's new design.

[40] As a result of a 2008 decision in an accessibility lawsuit filed by the American Council of the Blind, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing is planning to implement a raised tactile feature in the next redesign of each note, except the $1 and the current version of the $100 bill.

It also plans larger, higher-contrast numerals, more color differences, and distribution of currency readers to assist the visually impaired during the transition period.