History of the camera

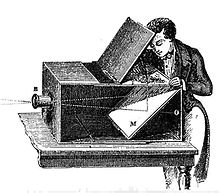

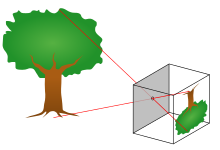

It projects an inverted image (flipped left to right and upside down) of a scene from the other side of a screen or wall through a small aperture onto a surface opposite the opening.

The earliest documented explanation of this principle comes from Chinese philosopher Mozi (c. 470 – c. 391 BC), who correctly argued that the inversion of the camera obscura image is a result of light traveling in straight lines from its source.

Johann Zahn envisioned the first camera small and portable enough for practical photography in 1685[citation needed], but it took nearly 150 years for such an application to become possible.

Ibn al-Haytham (c. 965 – 1040), an Arab physicist also known as Alhazen, made significant contributions to the understanding of the camera obscura, conducting experiments with light in a darkened room with a small opening.

[3][4] He also provided the first correct analysis of the camera obscura,[5] offering the first geometrical and quantitative descriptions of the phenomenon,[6] and was the first to utilize a screen in a dark room for image projection from a hole in the surface.

The work of Ibn al-Haytham on optics, circulated through Latin translations, played a significant role in inspiring notable individuals such as Witelo, John Peckham, Roger Bacon, Leonardo da Vinci, René Descartes, and Johannes Kepler.

[10]: 4 In a series of experiments, published in 1727, the German scientist Johann Heinrich Schulze demonstrated that the darkening of the salts was due to light alone, and not influenced by heat or exposure to air.

[10] To create images, Wedgwood placed items, such as leaves and insect wings, on ceramic pots coated with silver nitrate, and exposed the set-up to light.

Eventually, with help of the scientist and politician François Arago, the French government acquired Daguerre's process for public release.

[11]: 11 In the 1830s, the English scientist William Henry Fox Talbot independently invented a process to capture camera images using silver salts.

[15]: 7 In Germany, Peter Friedrich Voigtländer designed an all-metal camera with a conical shape that produced circular pictures of about 3 inches in diameter.

By 1840, exposure times were reduced to just a few seconds owing to improvements in the chemical preparation and development processes, and to advances in lens design.

Other cameras were fitted with multiple lenses for photographing several small portraits on a single larger plate, useful when making cartes de visite.

It was during the wet plate era that the use of bellows for focusing became widespread, making the bulkier and less easily adjusted nested box design obsolete.

It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer.

No means of removing the remaining unaffected silver chloride was known to Niépce, so the photograph was not permanent, eventually becoming entirely darkened by the overall exposure to light necessary for viewing it.

In the mid-1820s, Niépce used a wooden box camera made by Parisian opticians Charles and Vincent Chevalier, to experiment with photography on surfaces thinly coated with Bitumen of Judea.

After Niépce's death in 1833, his partner Louis Daguerre continued to experiment and by 1837 had created the first practical photographic process, which he named the daguerreotype and publicly unveiled in 1839.

The 1878 discovery that heat-ripening a gelatin emulsion greatly increased its sensitivity finally made so-called "instantaneous" snapshot exposures practical.

It was a very simple box camera with a fixed-focus lens and single shutter speed, which along with its relatively low price appealed to the average consumer.

Despite the advances in low-cost photography made possible by Eastman, plate cameras still offered higher-quality prints and remained popular well into the 20th century.

The Leica's immediate popularity spawned several of competitors, most notably the Contax (introduced in 1932), and cemented the position of 35 mm as the format of choice for high-end compact cameras.

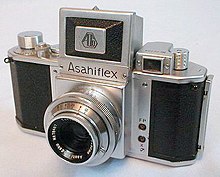

The fledgling Japanese camera industry began to take off in 1936 with the Canon 35 mm rangefinder, an improved version of the 1933 Kwanon prototype.

Japanese cameras would begin to become popular in the West after Korean War veterans and soldiers stationed in Japan brought them back to the United States and elsewhere.

The first major post-war SLR innovation was the eye-level viewfinder, which first appeared on the Hungarian Duflex in 1947 and was refined in 1948 with the Contax S, the first camera to use a pentaprism.

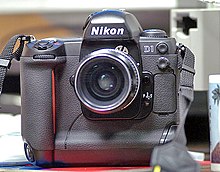

By the 1960s, however, low-cost electronic components were commonplace and cameras equipped with light meters and automatic exposure systems became increasingly widespread.

However, through-the-lens metering ultimately became a feature more commonly found on SLRs than other types of camera; the first SLR equipped with a TTL system was the Topcon RE Super of 1962.

Digital cameras now include wireless communication capabilities (for example Wi-Fi or Bluetooth) to transfer, print, or share photos, and are commonly found on mobile phones.

[33] At Philips Labs in New York, Edward Stupp, Pieter Cath and Zsolt Szilagyi filed for a patent on "All Solid State Radiation Imagers" on 6 September 1968 and constructed a flat-screen target for receiving and storing an optical image on a matrix composed of an array of photodiodes connected to a capacitor to form an array of two terminal devices connected in rows and columns.

The early adopters tended to be in the news media, where the cost was negated by the utility and the ability to transmit images by telephone lines.