History of the center of the Universe

With the development of the heliocentric model by Nicolaus Copernicus in the 16th century, the Sun was believed to be the center of the Universe, with the planets (including Earth) and stars orbiting it.

[3] The ancient Greeks regarded several sites as places of earth's omphalos (navel) stone, notably the oracle at Delphi, while still maintaining a belief in a cosmic world tree and in Mount Olympus as the abode of the gods.

Altars, incense sticks, candles and torches form the axis by sending a column of smoke, and prayer, toward heaven.

Structures such as the maypole, derived from the Saxons' Irminsul, and the totem pole among indigenous peoples of the Americas also represent world axes.

[6] In medieval times some Christians thought of Jerusalem as the center of the world (Latin: umbilicus mundi, Greek: Omphalos), and was so represented in the so-called T and O maps.

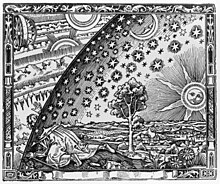

[citation needed] It was also typically held in the aboriginal cultures of the Americas, and a flat Earth domed by the firmament in the shape of an inverted bowl is common in pre-scientific societies.

Aristotle (384–322 BC) provided observational arguments supporting the idea of a spherical Earth, namely that different stars are visible in different locations, travelers going south see southern constellations rise higher above the horizon, and the shadow of Earth on the Moon during a lunar eclipse is round, and spheres cast circular shadows while discs generally do not.

Heliocentrism, or heliocentricism,[9][note 1] is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around a relatively stationary Sun at the center of the Solar System.

The notion that the Earth revolves around the Sun had been proposed as early as the 3rd century BC by Aristarchus of Samos,[10][11][note 2] but had received no support from most other ancient astronomers.

Johannes Kepler published his first two laws about planetary motion in 1609, having found them by analyzing the astronomical observations of Tycho Brahe.

In 1750 Thomas Wright, in his work An original theory or new hypothesis of the Universe, correctly speculated that the Milky Way might be a body of a huge number of stars held together by gravitational forces rotating about a Galactic Center, akin to the Solar System but on a much larger scale.

In 1785, William Herschel proposed such a model based on observation and measurement,[20] leading to scientific acceptance of galactocentrism, a form of heliocentrism with the Sun at the center of the Milky Way.

The 19th century astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler proposed the Central Sun Hypothesis, according to which the stars of the universe revolved around a point in the Pleiades.

As a result, Curtis became a proponent of the so-called "island Universes" hypothesis, which held that objects previously believed to be spiral nebulae within the Milky Way were actually independent galaxies.

[21] In 1920, the Great Debate between Harlow Shapley and Curtis took place, concerning the nature of the Milky Way, spiral nebulae, and the dimensions of the Universe.

[22] Edwin Hubble settled the debate about whether other galaxies exist in 1925 when he identified extragalactic Cepheid variable stars for the first time on astronomical photos of M31.

"[24]The redshift observations of Hubble, in which galaxies appear to be moving away from us at a rate proportional to their distance from us, are now understood to be associated with the expansion of the universe.