Observable universe

[11][12] As the universe's expansion is accelerating, all currently observable objects, outside the local supercluster, will eventually appear to freeze in time, while emitting progressively redder and fainter light.

In the future, light from distant galaxies will have had more time to travel, so one might expect that additional regions will become observable.

Regions distant from observers (such as us) are expanding away faster than the speed of light, at rates estimated by Hubble's law.

Assuming dark energy remains constant (an unchanging cosmological constant) so that the expansion rate of the universe continues to accelerate, there is a "future visibility limit" beyond which objects will never enter the observable universe at any time in the future because light emitted by objects outside that limit could never reach the Earth.

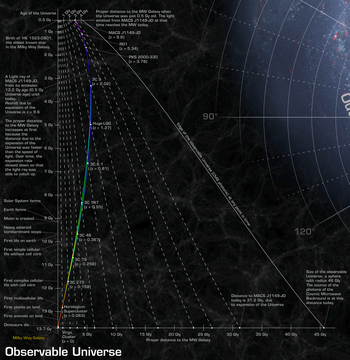

[9][15] This future visibility limit is calculated at a comoving distance of 19 billion parsecs (62 billion light-years), assuming the universe will keep expanding forever, which implies the number of galaxies that can ever be theoretically observed in the infinite future is only larger than the number currently observable by a factor of 2.36 (ignoring redshift effects).

It is difficult to test this hypothesis experimentally because different images of a galaxy would show different eras in its history, and consequently might appear quite different.

Bielewicz et al.[25] claim to establish a lower bound of 27.9 gigaparsecs (91 billion light-years) on the diameter of the last scattering surface.

[26] The comoving distance from Earth to the edge of the observable universe is about 14.26 gigaparsecs (46.5 billion light-years or 4.40×1026 m) in any direction.

This is the distance that a photon emitted shortly after the Big Bang, such as one from the cosmic microwave background, has traveled to reach observers on Earth.

[52] Although neutrinos are Standard Model particles, they are listed separately because they are ultra-relativistic and hence behave like radiation rather than like matter.

Sky surveys and mappings of the various wavelength bands of electromagnetic radiation (in particular 21-cm emission) have yielded much information on the content and character of the universe's structure.

[56] The organization of structure arguably begins at the stellar level, though most cosmologists rarely address astrophysics on that scale.

Prior to 1989, it was commonly assumed that virialized galaxy clusters were the largest structures in existence, and that they were distributed more or less uniformly throughout the universe in every direction.

In 1987, Robert Brent Tully identified the Pisces–Cetus Supercluster Complex, the galaxy filament in which the Milky Way resides.

That same year, an unusually large region with a much lower than average distribution of galaxies was discovered, the Giant Void, which measures 1.3 billion light-years across.

Two years later, astronomers Roger G. Clowes and Luis E. Campusano discovered the Clowes–Campusano LQG, a large quasar group measuring two billion light-years at its widest point, which was the largest known structure in the universe at the time of its announcement.

Another large-scale structure is the SSA22 Protocluster, a collection of galaxies and enormous gas bubbles that measures about 200 million light-years across.

On January 11, 2013, another large quasar group, the Huge-LQG, was discovered, which was measured to be four billion light-years across, the largest known structure in the universe at that time.

[62][64] In 2021, the American Astronomical Society announced the detection of the Giant Arc; a crescent-shaped string of galaxies that span 3.3 billion light years in length, located 9.2 billion light years from Earth in the constellation Boötes from observations captured by the Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

[66] The superclusters and filaments seen in smaller surveys are randomized to the extent that the smooth distribution of the universe is visually apparent.

This is a collection of absorption lines that appear in the spectra of light from quasars, which are interpreted as indicating the existence of huge thin sheets of intergalactic (mostly hydrogen) gas.

An early direct evidence for this cosmic web of gas was the 2019 detection, by astronomers from the RIKEN Cluster for Pioneering Research in Japan and Durham University in the U.K., of light from the brightest part of this web, surrounding and illuminated by a cluster of forming galaxies, acting as cosmic flashlights for intercluster medium hydrogen fluorescence via Lyman-alpha emissions.

[68][69] In 2021, an international team, headed by Roland Bacon from the Centre de Recherche Astrophysique de Lyon (France), reported the first observation of diffuse extended Lyman-alpha emission from redshift 3.1 to 4.5 that traced several cosmic web filaments on scales of 2.5−4 cMpc (comoving mega-parsecs), in filamentary environments outside massive structures typical of web nodes.

Gravitational lensing can make an image appear to originate in a different direction from its real source, when foreground objects curve surrounding spacetime (as predicted by general relativity) and deflect passing light rays.

Rather usefully, strong gravitational lensing can sometimes magnify distant galaxies, making them easier to detect.

At the centre of the Hydra–Centaurus Supercluster, a gravitational anomaly called the Great Attractor affects the motion of galaxies over a region hundreds of millions of light-years across.

This indicates that they are receding from us and from each other, but the variations in their redshift are sufficient to reveal the existence of a concentration of mass equivalent to tens of thousands of galaxies.

[72] In 2009, a gamma ray burst, GRB 090423, was found to have a redshift of 8.2, which indicates that the collapsing star that caused it exploded when the universe was only 630 million years old.