History of the extraterrestrial life debate

Initially, the question was purely speculative; in modern times a limited amount of scientific evidence provides some answers.

The debate continued during the Middle Ages, when the discussion centered upon whether the notion of extraterrestrial life was compatible with the doctrines of Christianity.

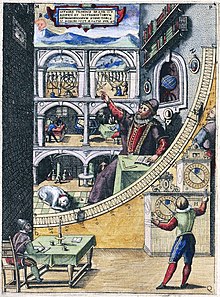

The Copernican Revolution radically altered mankind's image of the architecture of the cosmos by removing Earth from the center of the universe, which made the concept of extraterrestrial life more plausible.

Today we have no conclusive evidence of extraterrestrial life, but experts in many different disciplines gather to study the idea under the scientific umbrella of astrobiology.

During the early days of the history of astronomy the things seen in the night sky were explained as the actions of mythological deities.

However, it soon became evident that celestial objects move and behave in regular and predictable patterns, which helped in keeping track of time, tides, and seasons, crucial for ancient agriculture.

[1] Thales of Miletus sought to explain the nature of the universe without relying on supernatural explanations, and reasoned that Earth was a flat disk floating on an ocean of water.

However, their discussions laid some principles that would eventually lead to it, such as the rejection of supernatural explanations and that ideas would not be valid if they were contradicted by observable facts.

The model of the celestial sphere works for distant stars, which seem to be at fixed locations in the sky to the naked eye, but the Sun and the Moon move at different speeds and the other classical planets follow complex paths and vary in their brightness.

Aristarchus of Samos proposed instead that it is Earth that spins around the sun, which makes it easier to explain the retrograde motion of the classical planets, but this was rejected by other Greeks.

[6] Plato reasoned that there could be a single heaven, and that if there were several worlds the universe would be composite, eventually falling into dissolution and decay.

[7] Aristotle thought that the earth element would tend to fall to the center of the universe and fire to rise away from it, under that logic the existence of other worlds would not be possible.

Many Islamic scholars studied at the Library and cited or translated the work of the Greek authors, which did not get completely lost.

This knowledge spread across the Byzantine Empire, and finally returned to Europe when many scholars escaped from the fall of Constantinople.

A single world would also mean order, in contrast with the plurality of words held by atomists, who would believe in chance rather than in an "ordaining wisdom" creating it all.

In the following years several scholars discussed the plurality of worlds and maintained that it was not a theological impossibility, even if they rejected it for other reasons.

Although he correctly displaced the center of the Solar System, this first model turned out to be as inaccurate and as complex as the Ptolematic one, and did not get much supporters in the first decades.

[18][19] A recurring problem for both models was the lack of quality data, as the telescope had not been invented yet and naked eye observations are highly inaccurate.

On his deathbed, he asked his assistant Johannes Kepler to make sense of his observations, so that it did not feel like he lived in vain.

Kepler initially kept the circular orbits, and eventually found a system that would explain all the data, except for a mistake of 8 arcminutes on the position of Mars.

The newly invented telescope also revealed "imperfections" in celestial bodies: the sun was shown with sunspots, and the Moon has many features such as craters and mountain ranges.

The reason was finally explained by Sir Isaac Newton in his book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, which described the three laws of motion.

However, the only fact about this that was found at this time was that the stars and the classical planets are not lights but celestial objects analogous to Earth, and that life in them may be plausible, if still unknown.

Dominican philosopher Giordano Bruno accepted the existence of extraterrestrial life, which became one of the charges leveled against him at the Inquisition, leading to his execution.

Chemistry and biochemistry also help to understand abiogenesis, the process by which life can be generated by non-living things, which is not yet completely understood.

Physics in general and planetary science in particular help to understand the conditions at places other than Earth and how they can be more beneficial or harmful for life.