Tycho Brahe

King Frederick II granted Tycho an estate on the island of Hven and the money to build Uraniborg, the first large observatory in Christian Europe.

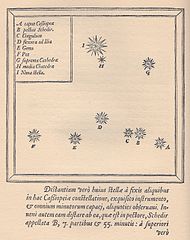

His measurements indicated that "new stars", stellae novae, now called supernovae, moved beyond the Moon, and he was able to show that comets were not atmospheric phenomena, as was previously thought.

His paternal grandfather and namesake, Thyge Brahe, was the lord of Tosterup Castle in Scania and died in battle during the 1523 Siege of Malmö during the Lutheran Reformation Wars.

Tycho later wrote that Jørgen Brahe "raised me and generously provided for me during his life until my eighteenth year; he always treated me as his own son and made me his heir".

[12] When Tycho and Vedel returned from Leipzig in 1565, Denmark was at war with Sweden, and as vice-admiral of the Danish fleet, Jørgen Brahe had become a national hero for having participated in the sinking of the Swedish warship Mars during the First battle of Öland (1564).

[16] In November 2012, Danish and Czech researchers reported that the prosthesis was actually made of brass after chemically analyzing a small bone sample from the nose from the body exhumed in 2010.

Soon, another uncle, Steen Bille, helped him build an observatory and alchemical laboratory at Herrevad Abbey, where Tycho was assisted by his keenest disciple, his younger sister Sophie Brahe.

After accepting this proposal, the location for the Uraniborg's construction was set on an island called Hven, now Ven in the Sound not too far from Copenhagen,[19] the earliest large observatory in Christian Europe.

Among them were Christian Sørensen Longomontanus, later one of the main proponents of the Tychonic model and Tycho's replacement as royal Danish astronomer, Peder Flemløse, Elias Olsen Morsing, and Cort Aslakssøn.

[43] The second volume, titled De Mundi Aetherei Recentioribus Phaenomenis Liber Secundus (Second Book About Recent Phenomena in the Celestial World) and devoted to the comet of 1577, was printed at Uraniborg and some copies were issued in 1588.

Prominent among them were John Craig, a Scottish physician who was a strong believer in the authority of the Aristotelian worldview, and Nicolaus Reimers Baer, known as Ursus, an astronomer at the Imperial court in Prague, whom Tycho accused of having plagiarized his cosmological model.

King Christian IV followed a policy of curbing the power of the nobility, by confiscating their estates to minimize their income bases, by accusing nobles of misusing their offices and of heresies against the Lutheran church.

Several gnesio-Lutheran Bishops suspected Tycho of heresy – a suspicion motivated by his known Philippist sympathies, his pursuits in medicine and alchemy, both of which he practiced without the church's approval, and his prohibiting the local priest on Hven to include the exorcism in the baptismal ritual.

[57] Tycho received financial support from several nobles in addition to the emperor, including Oldrich Desiderius Pruskowsky von Pruskow, to whom he dedicated his famous Mechanica.

[66] Before dying, he urged Kepler to finish the Rudolphine Tables and expressed the hope that he would do so by adopting Tycho's own planetary system, rather than that of the polymath Nicolaus Copernicus.

Given the limitations of the naked eye for making accurate observations, he devoted many of his efforts to improving the accuracy of the existing types of instrument – the sextant and the quadrant.

Cat D represents an unprecedented confluence of skills: instrumental, observational, & computational – all of which combined to enable Tycho to place most of his hundreds of recorded stars to an accuracy of ordermag 1'!"

[note 3] Celestial objects observed near the horizon and above appear with a greater altitude than the real one, due to atmospheric refraction, and one of Tycho's most important innovations was that he worked out and published the very first tables for the systematic correction of this possible source of error.

[86] To perform the huge number of multiplications needed to produce much of his astronomical data, Tycho relied heavily on the then-new technique of prosthaphaeresis, an algorithm for approximating products based on trigonometric identities that predated logarithms.

This instrument was kept still on a heavy duty base and adjusted via a brass plumb line and thumb screws, all of which helped give Tycho Brahe more accurate measurements of the heavens.

According to the accepted Aristotelian physics of the time, the heavens, whose motions and cycles were continuous and unending, were made of aether, a substance not found on Earth, that caused objects to move in a circle.

[100]Copernicans offered a religious response to Tycho's geometry: titanic, distant stars might seem unreasonable, but they were not, for the Creator could make his creations that large if He wanted.

[115] Another geocentric French astronomer, Jacques du Chevreul, rejected Tycho's observations including his description of the heavens and the theory that Mars was below the Sun.

[118] James Bradley's discovery of stellar aberration, published in 1729, eventually gave direct evidence excluding the possibility of all forms of geocentrism including Tycho's.

Early modern scholarship on Tycho tended to see the shortcomings of his astronomical model, painting him as a mysticist recalcitrant in accepting the Copernican revolution, and valuing mostly his observations that allowed Kepler to formulate his laws of planetary movement.

[27] In the second half of the 20th century, scholars began reevaluating his significance, and studies by Kristian Peder Moesgaard, Owen Gingerich, Robert Westman, Victor E. Thoren, John R. Christianson and C. Doris Hellman focused on his contributions to science, and demonstrated that while he admired Copernicus he was simply unable to reconcile his basic theory of physics with the Copernican view.

According to historian of science Helge Kragh, this assessment grew out of Gassendi's opposition to Aristotelianism and Cartesianism, and fails to account for the diversity of Tycho's activities.

Though, the poem's oft quoted line comes later: "Though my soul may set in darkness, it will rise in perfect light; / I have loved the stars too truly to be fearful of the night."

Alfred Noyes in his Watchers of the Sky (the first part of The Torch-bearers of 1922) included a long biographical poem in honour of Brahe, elaborating on the known history in a highly romantic and imaginative way.

Author Jerry Holkins' comic alter ego and online handle for Penny Arcade is named after the astronomer Tycho Brahe.