History of the oil shale industry in the United States

The second category of eastern oil-shale resources are the Paleozoic black shales, of lower oil yield, but of much larger size than the cannel coals.

[7] By 1853, Canadian geologist Abraham Gesner had learned to distill a good-quality lamp oil from a rock called “albertite,” found in New Brunswick, Canada.

Gesner moved from Halifax, Nova Scotia to New York City in early 1853, and in March 1853 he circulated a prospectus for the Asphalt Mining and Kerosene Gas Company.

The magazine said that the rush to establish coal-oil works resembled “a mania,” and attributed it to the “impetuous energy” of the American people.

[8] In the mid-1850s, whale-oil dealer Samuel Downer Jr. bought the near-bankrupt United States Chemical manufacturing company of Waltham, Massachusetts.

The first pattern was to place the retorts in or near a major market along the East Coast, and use shale or coal shipped long distances, usually imported from New Brunswick or Scotland.

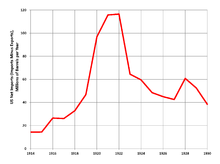

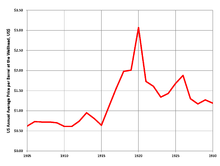

[20][21] Attracted by rising oil prices, and the promise of a permanent shortage of petroleum, oil-shale prospectors swarmed over the Piceance and Uinta basins of Colorado and Utah.

The American Continuous Retort plant in Denver was receiving test lots from western Colorado, and as far away as Texas and Kentucky, largely on the proprietor's claim that he could recover gold and platinum from the shale, along with the oil.

[23] Of the hundred-odd companies that formed to produce shale oil in the postwar boom, only Carlin's had actually done so on a commercial scale and marketed the product.

[24] The first attempts to exploit the Green River Formation deposit was made by establishment of The Oil Shale Mining Company in 1916.

[29][30] In 1925–1929, the retort was also tested by the United States Bureau of Mines in their Oil Shale Experiment Station at Anvil Point in Rifle, Colorado.

In 1964 the Avril Point demonstration facility was leased by Colorado School of Mines and was used by Mobil-led consortium (Mobil, Humble, Continental, Amoco, Phillips and Sinclair) for further development of that type of retort.

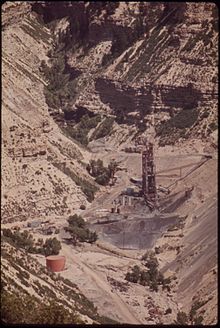

[23] In the early 1960s TOSCO (The Oil Shale Corporation) opened an underground mine and built an experimental plant near Parachute, Colorado.

[43][44] The federal government offered for lease three large blocks of oil shale land in Colorado in 1968, but rejected all the received bids as insufficient.

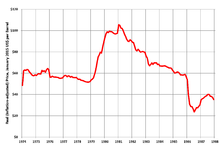

The highly influential 1972 Club of Rome report Limits to Growth predicted that the world was entering an era of increasingly scarce mineral resources.

[37] In 1972, the first modified in situ oil shale experiment in the United States was conducted by Occidental Petroleum at Logan Wash, Colorado.

Year later Ashland, Cleveland Cliffs Company and Sohio exited the Colony Shale Oil Project near Parachute, Colorado.

The company based its plans on its proprietary Paraho process retorting technology, which achieved oil recoveries of greater than 90 percent.

[51] Sunoco and Phillips Petroleum jointly submitted the US$76 million winning bid on the 5,120-acre Federal Tract U-a in Utah, and formed the White River Shale Oil Corporation to run the project.

SOHIO bought into the White River Corporation, and in 1975 the partners won the lease on the adjacent 5,120-acre U-b tract with a US$45 million bid.

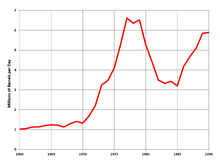

The company planned to produce 100,000 barrels of shale oil per day by underground mining and surface retorts, but both leases were suspended from 1976 and 1980 because of environmental and land title issue, stopping all development.

Occidental Petroleum Corporation had been began producing shale oil with in situ methods at its test tract near Debeque, Colorado.

[53] But as the projects developed, the companies found themselves with multibillion-dollar bets on the economic viability of oil shale, and some looked for partners to spread the risk; some sold out entirely.

The Colony Oil Shale Project changed hands a number of times, until the only original owner left was TOSCO with 40%.

In December 1981, Occidental Petroleum and Tenneco announced that they were suspending work on the Cathedral Bluffs project, and laying off hundreds of employees.

The community of Battlement Mesa, built to house the now laid-off employees of the Colony oil shale project, became an instant ghost town.

But the community was rescued from disappearance when its properties were marketed as retirement homes on Colorado's sunny western slope, and at a bargain price.

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1985 which among other things abolished the United States' Synthetic Liquid Fuels Program.

[citation needed] In 2016 Shell successfully tested its in situ process in Jordan, and later spun the technology out to create Salamander Solutions.

Shell Oil won three of the leases, to test three different methods, all in Rio Blanco County, Colorado; two of the projects would also recover the sodium mineral nahcolite.