History of railways in Württemberg

From the start of the 19th century, transport planning in the Kingdom of Württemberg revolved primarily around the construction of canals, which were meant to connect the rivers Neckar and Danube, and Lake Constance, with each other.

The report of the commission undertaking the study agreed and recommended the construction of a railway between Stuttgart and Ulm, running through the valleys of the rivers Rems, Kocher, and Brenz.

In the other larger states of the German Confederation (Deutscher Bund), such as Bavaria, Saxony, Prussia, Austria, Brunswick, Baden, and Hanover, at least one, and in some cases several, railways had been put into service by that time.

The late adoption was caused by the conclusion that the expensive construction of railways would not be cost-efficient in the relatively poor state.

The total cost of building the main railways was thought to be about 30 million guilders, which was three times the state's annual gross domestic product.

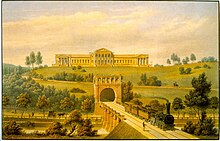

This relatively costly estimate was largely due to the hilly topography of Württemberg, and in particular the need to cross the Swabian Jura added to the expense.

This mountain range splits the state into two sections, and the steep escarpment on the northern edge, the Albtrauf, posed a particularly challenging obstacle.

The resulting central questions were: The Royal Württemberg State Railways (Königlich Württembergischen Staats-Eisenbahnen or K.W.St.E.)

The same law restricted the investment of private funds in the area of secondary connecting railways (Sekundärbahn).

Construction began in 1844, and the first section between Cannstatt und Untertürkheim was opened for service on 22 October 1845, with the entire line completed in 1846.

Both sides were convinced of the necessity of a railway connection on the one hand, but at the same time, both states were also interested in keeping the transit traffic from the north inside their territory as much as possible.

The direct route Bretten–Stuttgart–Ulm developed into the most important railway axis in Württemberg, and it came to be known as the Hauptbahn (Main line).

[1] Even though the main lines turned out to be economically successful, a lull in railway construction commenced for the next several years.

To open up the northeast of Württemberg, the initial plans called for a route from Heilbronn through the Kocher valley and via Hall to Aalen.

Also in 1861, the states of Württemberg and Bavaria signed a treaty, which codified the expansion of this line to Nördlingen, which was completed in 1863.

However, that treaty did include an unfavorable clause for Württemberg, which prohibited the direct connection between Aalen and Ulm (later to become the Brenz Railway) until 1875.

Added to this picture was the complication that both of these desired lines would need to run through the territory of Hohenzollern, which would require negotiations with Prussia.

In addition, Article 41 of the constitution enabled the Reich government to order the construction of railways for military purposes.

Also, the law legislating the management of the network as one unit offered the opportunity to Württemberg to finally achieve some of the connections which had been denied by neighbouring states on the basis of unwanted competition.

Württemberg had also finally reached an agreement with Bavaria on the construction of the Brenz Railway, which traveled across a section of Bavarian territory, and completed the connection between Heidenheim und Ulm.

In the Stuttgart area a few bypass lines were added to relieve the pressure on the main station at the state capital.

After World War I, the constitution of 1919 brought to an end the independence of the state railways; on 1 April 1920, they joined to form the Reichsbahn.

Among the railway openings worth mentioning before the start of World War II are the section Klosterreichenbach–Raumünzach on the Murg Valley Railway, completed in 1928, and the connection between Tuttlingen und Hattingen of 1934, which eliminated the hair pin curve in Immendingen for trains between Stuttgart and Singen.

The reason, as was the case in the rest of Germany, was the ever-increasing share of passenger traffic utilizing automobiles, which also became the preferred transport method supported by the national government.