History of transportation in New York City

[2] According to Burrow, et al.,[1] the Dutch had decided that that Lenape trail which ran the length of Manhattan, or present-day Broadway, would be called the Heere Wegh.

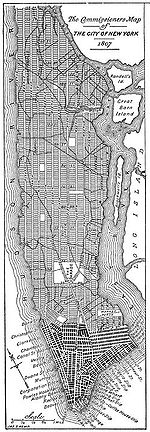

By the early 19th century, inland urban growth had reached approximately the line of the modern Houston Street, and farther in Greenwich Village.

[citation needed] Due to expanding world trade, growth was accelerating, and a commission created a more comprehensive street plan for the remainder of the island.

The economic logic underlying the plan – which called for twelve numbered avenues running approximately north and south, and 155 orthogonal cross streets – was that the grid's regularity would provide an efficient means to develop new real estate property and would promote commerce.

[4] Into the midd-19th century, most streets remained unpaved, but tracks allowed smooth public transport by horse cars which were eventually electrified as trolleys.

Water transport grew rapidly in the new century, due in part to technical development under Robert Fulton's steamboat monopoly.

[citation needed] Steamboats provided rapid, reliable connections from New York Harbor to other Hudson River and coastal ports, and later local steam ferries allowed commuters to live far from their workplaces.

[5] The first steam ferry service in the world began in 1812 between Paulus Hook and Manhattan[6] and reduced the journey time to a then-remarkable 14 minutes.

New York's ports continued to grow rapidly during and after the Second Industrial Revolution, making the city America's mouth, sucking in manufactured goods and immigrants and spewing forth grains and other raw materials to the developed countries.

Refineries and chemical factories followed in later decades, intensifying the conversion of Greenpoint, Bushwick, Maspeth and other outlying villages into industrial suburbs, later amalgamated into the City of Greater New York.

Roebling was unable to attend the ceremony (and in fact rarely visited the site again), but held a celebratory banquet at his house on the day of the bridge opening.

Soot and an occasional shower of flaming embers from overhead steam locomotives eventually came to be regarded as a nuisance, and the railroads were converted to electric operation.

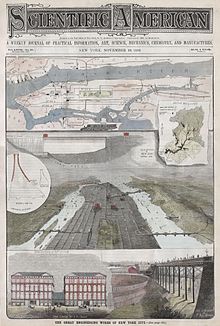

A competitive network of plank roads and surface and elevated railroads sprang up to connect and urbanize Long Island, especially the western parts.

The first elevated Manhattan (New York County) line was constructed in 1867-70 by Charles Harvey and his West Side and Yonkers Patent Railway company along Greenwich Street and Ninth Avenue (although operations began with cable cars).

During this era the expanded City of New York resolved that it wanted the core of future rapid transit to be underground subways, but realized that no private company was willing to put up the enormous capital required to build beneath the streets.

[14][15] The City decided to issue rapid transit bonds outside of its regular bonded debt limit and build the subways itself, and contracted with the IRT (which by that time ran the elevated lines in Manhattan) to equip and operate the subways, sharing the profits with the city and guaranteeing a fixed five-cent fare later confirmed in the Dual Contracts.

The Queens airports grew and prospered in later decades, but the Floyd Bennett Field eventually was closed to regular passenger service.

John D. Hertz started the Yellow Cab Company in 1915, which operated hireable vehicles in a number of cities including New York.

In the late 1910s, Mayor John Francis Hylan authorized a system of "emergency bus lines" managed by the Department of Plant and Structures.

The Lincoln and Holland tunnels were built instead of bridges to allow free passage of large passenger and cargo ships in the port, which were still critical for New York City's industry through the early- to mid-20th century.

The Port Authority oversaw the transition of the ocean cargo industry from North River break bulk operations to containerization ports, mostly on Newark Bay, built a Downtown truck terminal on Greenwich Street and Midtown bus terminal, and took over the financially ailing Hudson Tubes that carried commuters from Hudson and Essex Counties in New Jersey to Manhattan.

Plans for a Cross-Harbor Rail Tunnel to replace the declining car float operations of the railroads did not come to fruition; instead, most land freight traffic converted to trucks.

A catalyst for expressways and suburbs, but a nemesis for environmentalists and politicians alike, Robert Moses was a critical figure in reshaping the very surface of New York, adapting it to the changed methods of transportation after 1930.

Since the early 2000s, many proposals for expanding or improving the New York City transit system have been in various stages of discussion, planning, or initial funding.

As part of PlaNYC 2030, a long-term plan to manage New York City's environmental sustainability, Mayor Michael Bloomberg released several proposals to increase mass transit usage and improve overall transportation infrastructure.

[37] The adjacent World Trade Center Transportation Hub for the PATH, began construction in late 2005 and opened on March 4, 2016, at a cost of $3.74 billion.

[44] East Side Access project, opened in January 2023,[45] routes some Long Island Rail Road trains to Grand Central Madison instead of Penn Station.

[46][47] The Gateway Project, set for completion by 2026, will add a second pair of railroad tracks under the Hudson River, connecting an expanded Penn Station to NJ Transit and Amtrak lines.

[54] Bloomberg's other proposals included the implementation of bus rapid transit, the reopening of closed LIRR and Metro-North stations, new ferry routes, better access for cyclists, pedestrians and intermodal transfers, and a congestion pricing zone for Manhattan south of 86th Street.

[59] Although Bloomberg's congestion pricing plan was initially shot down in 2008,[60][61] Governor Andrew Cuomo gave the idea renewed consideration in 2017.