History of the New York City Subway

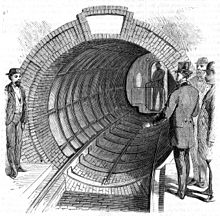

During this era the expanded City of New York resolved that it wanted the core of future rapid transit to be underground subways but realized that no private company was willing to put up the enormous capital required to build beneath the streets.

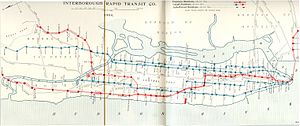

The act provided that the commission would lay out routes with the consent of property owners and local authorities, either build the system or sell a franchise for its construction, and lease the operation to a private firm.

The trains began operating their regular schedules ahead of time, and all stations of the Eighth Avenue Line, from 207th Street in Inwood to Hudson Terminal (now World Trade Center), opened simultaneously at one minute after midnight on September 10, 1932.

[43] New York hoped that the profits from the remaining formerly privately operated routes would support the expensive and deficit-ridden IND lines and simultaneously be able to repay the systems' debts, without having to increase the original fare of five cents.

In addition, signs were fitted incorrectly, and spare parts were missing or were bought in too large quantities, could not be found, or could not be installed due to lack of repairmen.

[152] The New York City Subway tried to keep its budget balanced between spending and revenue, so deferred maintenance became more common, which drew a slow but steady decline of the system and rolling stock.

[158] In the mid-1960s, US$600,000,000 was made available to the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) of New York City for a large subway expansion proposed by then-Mayor John Lindsay.

The MTA reduced the length of trains during off-peak periods, and canceled work on several projects being built as part of the Program for Action, including the Second Avenue Subway and an LIRR line through the 63rd Street Tunnel to a Metropolitan Transportation Center in East Midtown, Manhattan.

[173] In 1986, the NYCTA launched a study to determine whether to close 79 stations on 11 routes, spread across all four of the boroughs that the subway system served, due to low ridership and high repair costs.

[177] Even though each of the approximately 7,200 subway cars were checked once every six weeks or 7,500 miles (12,100 km) of service, four or five dead motors were allowable in a peak-hour 10-car train, according to some transit workers' accounts.

[181] Operations in 1981 had deteriorated so that:[182][183] In 1986, the MTA and Regional Plan Association again considered closing 26 miles (42 km) of above-ground lines to follow population shifts.

The IRT Lexington Avenue Line was known to frequent muggers, so in February 1979, Curtis Sliwa's Guardian Angels group began patrolling the 4 train during the night.

[192] A series of window-smashing incidents on subway cars started in 1980 on the IRT Pelham Line and spread throughout the rest of the system, causing delays when damaged trains needed to be taken out of service.

In July 1985, the Citizens Crime Commission of New York City published a study showing this trend, fearing the frequent robberies and generally bad circumstances.

[200][201][202] In the early afternoon of December 22, 1984, Bernhard Goetz shot four young African American men from the Bronx on a New York City Subway train.

That day, the men—Barry Allen, Troy Canty, Darrell Cabey (all 19), and James Ramseur (18)—boarded a downtown 2 train (Broadway – Seventh Avenue Line express) carrying screwdrivers, apparently on a mission to steal money from video arcade machines in Manhattan.

[208] The incident sparked a nationwide debate on race and crime in major cities, the legal limits of self-defense, and the extent to which the citizenry could rely on the police to secure their safety.

[209] Although Goetz, dubbed the "Subway Vigilante" by New York City's press, came to symbolize New Yorkers' frustrations with the high crime rates of the 1980s, he was both praised and vilified in the media and public opinion.

[153] Existing elevated structures posed a large danger; the New York Post published a story that featured debris that had fallen from the BMT Astoria Line.

[237] The RPA also suggested:[236] In April 1986, the New York City Transit Authority began to study the possibility of eliminating sections of 11 subway lines because of low ridership.

The lines were first identified in the first part of a three-year project, the Strategic Plan Initiative, which started in April 1985, by the MTA to evaluate the region's bus, subway, and commuter rail systems.

[247][248] Service on the BMT Broadway Line was also disrupted because the tracks from the Montague Street Tunnel run adjacent to the World Trade Center and there were concerns that train movements could cause unsafe settling of the debris pile.

The project, which was the first one funded by the city in over 60 years,[265] was intended to aid redevelopment of Hell's Kitchen around the West Side Yard of the Long Island Rail Road.

This required the NYCTA to truck in 20 R32 subway cars to the line to provide some interim service, which was temporarily designated the H.[271][272] The H ran between Beach 90th Street and Far Rockaway–Mott Avenue, where passengers could transfer to a free shuttle bus.

[317][319] To solve the system's problems, the MTA officially announced the Genius Transit Challenge on June 28, 2017, where contestants could submit ideas to improve signals, communications infrastructure, or rolling stock.

For instance, in February 2019, several politicians wrote a letter to the MTA, asking the agency to consider splitting the R train in half to increase reliability.

[354][355] In February 2021, the New York City Subway removed benches from several stations in an effort to reduce the number of homeless persons sleeping on them, which during the COVID-19 pandemic was considered to be unsanitary.

This move drew considerable backlash from riders who alleged that the removal of the benches amounts to disenfranchising disabled people and senior citizens, as well as being unfair to homeless populations.

[360] During the pandemic, the subway system experienced several high-profile incidents, including a January 2022 shoving death of a passenger in Times Square and an April 2022 mass shooting in Brooklyn.

[370] In 2024, as part of its 2025–2029 Capital Program, the MTA announced that it would spend billions of dollars on new rolling stock, upgraded signals, and accessibility projects at 60 subway stations.