History of turnpikes and canals in the United States

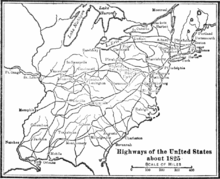

The history of turnpikes and canals in the United States began with work attempted and accomplished in the original thirteen colonies, predicated on European technology.

The preliminary report of the Inland Waterways Commission in 1808 provides a description of the early development of transportation and communication infrastructure: "The earliest movement toward developing the inland waterways of the country began when, under the influence of George Washington, Virginia and Maryland appointed commissioners primarily to consider the navigation and improvement of the Potomac; they met in 1786 in Alexandria and adjourned to Mount Vernon, where they planned for extension, pursuant to which they reassembled with representatives of other States in Annapolis in 1786; again finding the task a growing one, a further conference was arranged in Philadelphia in 1787, with delegates from all the States.

There the deliberations resulted in the framing of the Constitution, whereby the thirteen original States were united primarily on a commercial basis — the commerce of the times being chiefly by water.

The British coastal blockade in the War of 1812, and an inadequate internal capability to respond, demonstrated the United States' reliance upon such overland roads for military operations as well as for general commerce.

[9] When the project was completed in 1825, the canal linked the Hudson River to Lake Erie via 83 separate locks and over a distance of 363 miles (584 km).

This bold bid for the western trade to their north alarmed the competing merchants of Philadelphia, since the completion of the National Road also threatened to divert much of their traffic south to Baltimore.

In 1825, the legislature of Pennsylvania grappled with the problem by projecting a series of canals to connect Philadelphia with Pittsburgh in the west and with Lake Erie and the upper Susquehanna to the north.

Following the war, the United States soon developed an expanded system of more modern fortifications to provide the first line of land defense against the threat of attack from European powers.

In much alarm Jefferson suggested to Madison the desirability of having Virginia adopt a new set of resolutions, founded on those of 1798, and directed against the acts for internal improvements.

As early as 1807, Albert Gallatin had advocated the construction of a great system of internal waterways to connect East and West, at an estimated cost of $20,000,000.

However, the only contribution of the federal government to internal improvements during the Jeffersonian era was an appropriation in 1806 of two percent of the net proceeds of the sales of public lands in Ohio for the construction of a national road, with the consent of the states through which it should pass.

In the Presidential campaign of 1824, Speaker of the House Henry Clay, the foremost proponent of the 'American System', pleaded for a larger conception of the functions of the national government.

He called attention to provisions made for coastal surveys and lighthouses on the Atlantic seaboard and deplored the neglect of the interior of the country.

Senator and war-hero Andrew Jackson voted for the General Survey Act, as did Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who left no doubt that he did not support the narrow views of his New England region on this issue.

In March 1826 the Virginia general assembly declared that all the principles of their earlier resolutions applied "with full force against the powers assumed by Congress" in passing acts to further internal improvements and to protect manufacturers.