History of women in Germany

The history of German women covers gender roles, personalities and movements from medieval times to the present in German-speaking lands.

The Ottonian queens and empresses (including Matilda of Ringelheim, Adelaide of Italy, Theophanu, Cunigunde of Luxembourg) were among the most powerful women of the entire Middle Age.

[4][6][7] Abbesses, especially those of Imperial abbeys wielded tremendous power, with influence encompassing spiritual, economic, political and intellectual realms.

[24] When the imperial throne became practically hereditary under the Habsburgs in the Early Modern period, the effort to make the princess Maria Theresa his heir by Emperor Charles VI met with many difficulties.

While most European governments recognized his Pragmatic Sanction (that would allow female right of succession), in practice, Maria Theresa's inheritance was still contested.

Jestice and Görich write that Ottonian sources reveal no misogyny and basically the society recognized the roles and abilities (except physical strength) of women, thus the commonly deemed special status of empresses and queens actually did not stand out in this context.

[29][30] The early sixteenth century epic collection Ambraser Heldenbuch, one of the most important works of medieval German literature, focuses largely on female characters (with notable texts being its versions of the Nibelungenlied, the Kudrun and the poem Nibelungenklage) and defends the concept of Frauenehre (female honour) against the increasing misogyny of the time.

Under German laws, women had property rights over their dowries and inheritances, a valuable benefit as high mortality rates resulted in successive marriages.

While priests' concubines had previously received some degree of social acceptance, marriage did not necessarily remove the stigma of concubinage, nor could a wife claim the wage to which a female servant might be entitled.

[35] According to Kay Goodman, feminist scholars trace the beginning of German female literature (which paved the way for nineteenth-century feminism) to the era of Romanticism (eighteenth century).

Dorothea Erxleben, the first German woman doctor, challenged the social restrictions on the role of women, that defined them only as wives, mothers and caretakers.

[40] Some of the most notable German businesswomen of this period included Glückel of Hameln, Anna Vandenhoeck, Karoline Kaulla, Aletta Haniel, Helene Amalie Krupp.

[41][42][43] Katharina Henot, possibly the first German postmistress, was executed as an alleged witch in the midst of a legal battle between her family and the House of Thurn und Taxis.

[50][51] In the nineteenth century, the literary salons (generally presided over by women) played a great role in civilizing society.

[53][54] Fanny Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann were the two notable female composers of the nineteenth century, although they only began to receive recognition long after their deaths.

[60] A major social change 1750-1850 Depending on the region, was the end of the traditional whole house" ("ganzes Haus") system, in which the owner's family lived together in one large building with the servants and craftsmen he employed.

Farm wives supervised family care and the household interior, to which strict standards of cleanliness, order, and thrift were applied.

[67] Germany's unification process after 1871 was heavily dominated by men and gave priority to the "Fatherland" theme and related male issues, such as military prowess.

From the beginning the BDF was a bourgeois organization, its members working toward equality with men in such areas as education, financial opportunities, and political life.

On a visit to Germany, Clarke observed that: "German peasant girls and women work in the field and shop with and like men.

Physicians, furthermore, paid much more attention to diet, emphasizing that the combination of scientific selection of ingredients and high quality preparation was therapeutic for patients with metabolic disturbances.

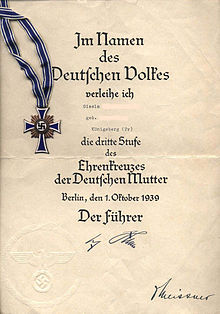

The Nazi doctrine elevated the role of German men, emphasizing their combat skills and the brotherhood among male compatriots.

[82] Women lived within a regime characterized by a policy of confining them to the roles of mother and spouse and excluding them from all positions of responsibility, notably in the political and academic spheres.

The policy of Nazism contrasted starkly with the evolution of emancipation under the Weimar Republic, and is equally distinguishable from the patriarchal and conservative attitude under the German Empire, 1871–1919.

The regimentation of women at the heart of satellite organizations of the Nazi Party, as the Bund Deutscher Mädel or the NS-Frauenschaft, had the ultimate goal of encouraging the cohesion of the "people's community" Volksgemeinschaft.

Women only had a limited right to training revolving around domestic tasks, and were, over time, restricted from teaching in universities, from medical professions and from serving in political positions within the NSDAP.

Historians have paid special attention to the efforts by Nazi Germany to reverse the gains women made before 1933, especially in the relatively liberal Weimar Republic.

As Germany prepared for war, large numbers were incorporated into the public sector and with the need for full mobilization of factories by 1943, all women were required to register with the employment office.

[97] By winning more than 30% of the Bundestag seats in 1998, women reached a critical mass in leadership roles in the coalition of the Social Democratic and Green parties.

Women in high office have pushed through important reforms in areas of gender and justice; research and technology; family and career; health, welfare, and consumer protection; sustainable development; foreign aid; migration; and human rights.