History painting

[5] This view remained general until the 19th century, when artistic movements began to struggle against the establishment institutions of academic art, which continued to adhere to it.

In some 19th or 20th century contexts, the term may refer specifically to paintings of scenes from secular history, rather than those from religious narratives, literature or mythology.

The term is generally not used in art history in speaking of medieval painting, although the Western tradition was developing in large altarpieces, fresco cycles, and other works, as well as miniatures in illuminated manuscripts.

In the Late Renaissance and Baroque the painting of actual history tended to degenerate into panoramic battle-scenes with the victorious monarch or general perched on a horse accompanied with his retinue, or formal scenes of ceremonies, although some artists managed to make a masterpiece from such unpromising material, as Velázquez did with his The Surrender of Breda.

Celui qui peint des animaux vivants est plus estimable que ceux qui ne représentent que des choses mortes & sans mouvement; & comme la figure de l'homme est le plus parfait ouvrage de Dieu sur la Terre, il est certain aussi que celui qui se rend l'imitateur de Dieu en peignant des figures humaines, est beaucoup plus excellent que tous les autres ... un Peintre qui ne fait que des portraits, n'a pas encore cette haute perfection de l'Art, & ne peut prétendre à l'honneur que reçoivent les plus sçavans.

From 1760 onwards, the Society of Artists of Great Britain, the first body to organize regular exhibitions in London, awarded two generous prizes each year to paintings of subjects from British history.

When, in 1770, Benjamin West proposed to paint The Death of General Wolfe in contemporary dress, he was firmly instructed to use classical costume by many people.

Although George III refused to purchase the work, West succeeded both in overcoming his critics' objections and inaugurating a more historically accurate style in such paintings.

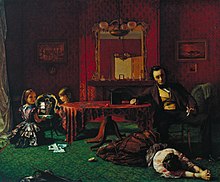

Another development in the nineteenth century was the treatment of historical subjects, often on a large scale, with the values of genre painting, the depiction of scenes of everyday life, and anecdote.

At the same time scenes of ordinary life with moral, political or satirical content became often the main vehicle for expressive interplay between figures in painting, whether given a modern or historical setting.

Another path was to choose contemporary subjects that were oppositional to government either at home and abroad, and many of what were arguably the last great generation of history paintings were protests at contemporary episodes of repression or outrages at home or abroad: Goya's The Third of May 1808 (1814), Théodore Géricault's The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), Eugène Delacroix's The Massacre at Chios (1824) and Liberty Leading the People (1830).

Romantic artists such as Géricault and Delacroix, and those from other movements such as the English Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood continued to regard history painting as the ideal for their most ambitious works.

Others such as Jan Matejko in Poland,[15] Vasily Surikov in Russia, José Moreno Carbonero in Spain and Paul Delaroche in France became specialized painters of large historical subjects.

An example of this is the extensive research of Byzantine architecture, clothing, and decoration made in Parisian museums and libraries by Moreno Carbonero for his masterwork The Entry of Roger de Flor in Constantinople.

[19] New techniques of printmaking such as the chromolithograph made good quality reproductions both relatively cheap and very widely accessible, and also hugely profitable for artist and publisher, as the sales were so large.