Judas Iscariot

Judas Iscariot (/ˈdʒuːdəs ɪˈskæriət/; Biblical Greek: Ἰούδας Ἰσκαριώτης, romanized: Ioúdas Iskariṓtēs; died c. 30 – c. 33 AD) was, according to Christianity's four canonical gospels, one of the original Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ.

Judas betrayed Jesus to the Sanhedrin in the Garden of Gethsemane, in exchange for 30 pieces of silver, by kissing him on the cheek and addressing him as "master" to reveal his identity in the darkness to the crowd who had come to arrest him.

According to Matthew 27:1–10, after learning that Jesus was to be crucified, Judas attempted to return the money he had been paid for his betrayal to the chief priests and hanged himself.

The Book of Acts 1:18 quotes Peter as saying that Judas used the money to buy the field himself and, he "[fell] headlong... burst asunder in the midst, and all his bowels gushed out."

His betrayal is seen as setting in motion the events that led to Jesus's crucifixion and resurrection, which, according to traditional Christian theology brought salvation to humanity.

[5] The earliest possible allusion to Judas comes from the First Epistle to the Corinthians 11:23–24, in which Paul the Apostle does not mention Judas by name[8][9] but uses the passive voice of the Greek word paradídōmi (παραδίδωμι), which most Bible translations render as "was betrayed":[8][9] "...the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took a loaf of bread..."[8] Nonetheless, some biblical scholars argue that the word paradídōmi should be translated as "was handed over".

[23][24] Stanford rejects this, arguing that the gospel writers follow Judas's name with the statement that he betrayed Jesus, so it would be redundant for them to call him "the false one" before immediately stating that he was a traitor.

[4][17] Ehrman also contends that it is highly unlikely that early Christians would have made up the story of Judas's betrayal, since it reflects poorly on Jesus's judgment in choosing him as an apostle.

[37][38] Matthew 27:1–10 states that after learning that Jesus was to be crucified, Judas was overcome by remorse and attempted to return the 30 pieces of silver to the priests, but they would not accept them because they were blood money, so he threw them on the ground and left.

[39] The early Church Father Papias of Hierapolis records in his Expositions of the Sayings of the Lord (which was probably written around 100 AD) that Judas was afflicted by God's wrath;[42][43] his body became so enormously bloated that he could not pass through a street with buildings on either side.

[42] Finally, he killed himself on his own land by pouring out his innards onto the ground,[42][43] which stank so horribly that, even in Papias's own time a century later, people still could not pass the site without holding their noses.

[43] According to the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus, which was probably written in the fourth century AD, Judas was overcome with remorse[44] and went home to tell his wife, who was roasting a chicken on a spit over a charcoal fire, that he was going to kill himself, because he knew Jesus would rise from the dead and, when he did, he would punish him.

[43] Generally they have followed literal interpretations such as that of Augustine of Hippo, which suggest that these simply describe different aspects of the same event—that Judas hanged himself in the field, and the rope eventually snapped and the fall burst his body open,[47][48] or that the accounts of Acts and Matthew refer to two different transactions.

"[43] David A. Reed argues that the Matthew account is a midrashic exposition that allows the author to present the event as a fulfillment of prophetic passages from the Old Testament.

[58] Raymond Brown suggests "the most plausible [explanation] is that Matthew 27:9–10 is presenting a mixed citation with words taken both from Zechariah and Jeremiah, and ... he refers to that combination by one name.

"[59] Classicist Glenn W. Most suggests that Judas's death in Acts can be interpreted figuratively, writing that πρηνὴς γενόμενος should be translated as saying his body went prone, rather than falling headlong, and the spilling of the entrails is meant to invoke the imagery of dead snakes and their burst-open bellies.

[85] In his 1965 book The Passover Plot, British New Testament scholar Hugh J. Schonfield suggests that the crucifixion of Christ was a conscious re-enactment of Biblical prophecy and that Judas acted with the full knowledge and consent of Jesus in "betraying" him to the authorities.

In the Gospel of Matthew, after the Sanhedrin condemns Jesus Christ to death, are added the comments concerning Judas: "...late repentance brings desperation" (cf.

[93] The Catholic Church took no specific view concerning the damnation of Judas during Vatican II; speaking in generalities, that Council stated, "[We] must be constantly vigilant so that ... we may not be ordered to go into the eternal fire (cf.

[95] However, while that section of the catechism does instruct Catholics that the personal sin of Judas is unknown but to God, that statement is within the context that the Jewish people have no collective responsibility for Jesus's death: "... the Jews should not be spoken of as rejected or accursed as if this followed from holy Scripture.

[97] The Catechism of the Council of Trent, which mentions Judas Iscariot several times, wrote that he possessed "motive unworthy" when he entered the priesthood and was thus sentenced to "eternal perdition".

[104] Within the 1962 Roman Missal for the Tridentine Latin Mass, the Collect for Holy Thursday states: "O God, from whom Judas received the punishment of his guilt, and the thief the reward of his confession ... our Lord Jesus Christ gave to each a different recompense according to his merits..."[105] In his commentary on the Liturgical Year, Abbot Gueranger, O.S.B.

In the Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri, Judas is punished for all eternity in the ninth circle of Hell: in it, he is devoured by Lucifer, alongside Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus (leaders of the group of senators that assassinated Julius Caesar).

In his 1969 book Theologie der Drei Tage (English translation: Mysterium Paschale), Hans Urs von Balthasar emphasizes that Jesus was not betrayed but surrendered and delivered up by himself, since the meaning of the Greek word used by the New Testament, paradidonai (παραδιδόναι, Latin: tradere), is unequivocally "handing over of self".

[107][108] In the "Preface to the Second Edition", Balthasar takes a cue from Revelation 13:8[citation needed] (Vulgate: agni qui occisus est ab origine mundi, NIV: "the Lamb who was slain from the creation of the world") to extrapolate the idea that God as "immanent Trinity" can endure and conquer godlessness, abandonment, and death in an "eternal super-kenosis".

Irenaeus records the beliefs of one Gnostic sect, the Cainites, who believed that Judas was an instrument of the Sophia, Divine Wisdom, thus earning the hatred of the Demiurge.

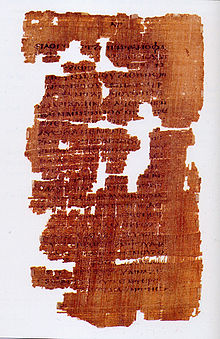

The discovery was given dramatic international exposure in April 2006 when the US National Geographic magazine published a feature article entitled "The Gospel of Judas" with images of the fragile codex and analytical commentary by relevant experts and interested observers (but not a comprehensive translation).

"[119] The article points to some evidence that the original document was extant in the 2nd century: "Around A.D. 180, Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon in what was then Roman Gaul, wrote a massive treatise called Against Heresies [in which he attacked] a 'fictitious history,' which 'they style the Gospel of Judas.

'"[121] The National Geographic Society responded that "Virtually all issues April D. DeConick raises about translation choices are addressed in footnotes in both the popular and critical editions.

This gospel is considered by the majority of Christians to be late and pseudepigraphical; however, some academics suggest that it may contain some remnants of an earlier apocryphal work (perhaps Gnostic, Ebionite, or Diatessaronic), redacted to bring it more in line with Islamic doctrine.