Home computer

Early microcomputers such as the Altair 8800 had front-mounted switches and diagnostic lights (nicknamed "blinkenlights") to control and indicate internal system status, and were often sold in kit form to hobbyists.

Ports for plug-in peripheral devices such as a video display, cassette tape recorders, joysticks, and (later) disk drives were either built-in or available on expansion cards.

To save the cost of a dedicated monitor, the home computer would often connect through an RF modulator to the family TV set, which served as both video display and sound system.

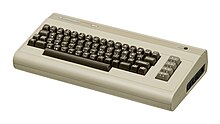

[19] After the success of the Radio Shack TRS-80, the Commodore PET, and the original Apple II in 1977, almost every manufacturer of consumer electronics rushed to introduce a home computer.

The BBC Micro, Sinclair ZX Spectrum, Atari 8-bit computers, and Commodore 64 sold many units over several years and attracted third-party software development.

Another capability home computers had that game consoles of the time lacked was the ability to access remote services over telephone lines by adding a serial port interface, a modem, and communication software.

Applying a patch to modify software to be compatible with one's system, or writing a utility program to fit one's needs, was a skill every advanced computer owner was expected to have.

[29][30][31] In 1990, the company reportedly refused to support joysticks on its low-cost Macintosh LC and IIsi computers to prevent customers from considering them as "game machines".

By 1986, industry experts predicted an "MS-DOS Christmas", and the magazine stated that clones threatened Commodore, Atari, and Apple's domination of the home-computer market.

[31] The declining cost of IBM compatibles on the one hand, and the greatly-increased graphics, sound, and storage abilities of fourth generation video game consoles such as the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo Entertainment System on the other, combined to cause the market segment for home computers to vanish by the early 1990s in the US.

In Europe, the home computer remained a distinct presence for a few years more, with the low-end models of the 16-bit Amiga and Atari ST families being the dominant players, but by the mid-1990s, even the European market had dwindled.

An important exception was the Radio Shack TRS-80, the first mass-marketed computer for home use, which included its own 64-column display monitor and full-travel keyboard as standard features.

Almost universally, the floppy disk drives available for 8-bit home computers were housed in external cases, with their own controller boards and power supplies contained within.

In addition, the small size and limited scope of home computer "operating systems" (really little more than what today would be called a kernel) left little room for bugs to hide.

However, in the following years, technological advances and improved manufacturing capabilities (mainly greater use of robotics and relocation of production plants to lower-wage locations in Asia) permitted several computer companies to offer lower-cost, PC-style machines that would become competitive with many 8-bit home-market pioneers like Radio Shack, Commodore, Atari, Texas Instruments, and Sinclair.

Its designers took minor shortcuts, such as few expansion slots and a lack of a socket for an 8087 math chip, but Epson did bundle some utility programs that offered decent turnkey functionality for novice users.

[50][51] This was positioned as an "appliance" computer much like the original Apple Macintosh: turnkey startup, built-in monochrome video monitor, and lacking expansion slots, requiring proprietary add-ons available only from Zenith, but instead with the traditional MS-DOS Command-line interface.

Throughout the 1980s, costs and prices continued to be driven down by: advanced circuit design and manufacturing, multi-function expansion cards, shareware applications such as PC-Talk, PC-Write, and PC-File, greater hardware reliability, and more user-friendly software that demanded less customer support services.

Microsoft developed the MSX-DOS operating system, a version of their popular MS-DOS adapted to the architecture of these machines, that was also able to run CP/M software directly After the first wave of game consoles and computers landed in American homes, the United States Federal Communications Commission (FCC) began receiving complaints of electromagnetic interference to television reception.

"[59] Despite Olsen's warning, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, from about 1977 to 1983, it was widely predicted[60] that computers would soon revolutionize many aspects of home and family life as they had business practices in the previous decades.

Even if the computers could be used for multiple purposes simultaneously as today, other technical limitations predominated; memory capacities were too small to hold entire encyclopedias or databases of financial records;[71] floppy disk-based storage was inadequate in both capacity and speed for multimedia work;[72] and the home computers' graphics chips could only display blocky, unrealistic images and blurry, jagged text that would be difficult to read a newspaper from.

[74][75][76] The Boston Phoenix stated in 1983 that "people are catching on to the fact that 'applications' like balancing your checkbook and filing kitchen recipes are actually faster and easier to do with a pocket calculator and a box of index cards".

The computers that were bought for use in the family room were either forgotten in closets or relegated to basements and children's bedrooms to be used exclusively for games and the occasional book report.

[81] In 1984 Tandy executive Steve Leininger, designer of the TRS-80 Model I, admitted that "As an industry we haven't found any compelling reason to buy a computer for the home" other than for word processing.

With better network connectivity and speed, resources such as encyclopedias, recipe catalogs and medical databases moved online and are now accessed over the Internet, with local storage solutions like floppy disks and CD-ROM's falling out of use for these purposes during those decades.

In an example of changing applications for technology, before the invention of radio, the telephone was used to distribute opera and news reports, whose subscribers were denounced as "illiterate, blind, bedridden and incurably lazy people".

As programming techniques evolved and these systems were well-understood after decades of use, it became possible to write software giving home computers capabilities undreamed of by their designers.

The Contiki OS implements a GUI and TCP/IP stack on the Apple II, Commodore 8-bit and Atari ST (16-bit) platforms, allowing these home computers to function as both internet clients and servers.

[88] As their often-inexpensively manufactured hardware ages and the supply of replacement parts dwindles, it has become popular among enthusiasts[89] to emulate these machines, recreating their software environments[90] on modern computers.

Home computers use floppy disks for mass storage and perform useful functions like word processing and income tax preparation as well as playing games.