Homological algebra

It is a relatively young discipline, whose origins can be traced to investigations in combinatorial topology (a precursor to algebraic topology) and abstract algebra (theory of modules and syzygies) at the end of the 19th century, chiefly by Henri Poincaré and David Hilbert.

Homological algebra is the study of homological functors and the intricate algebraic structures that they entail; its development was closely intertwined with the emergence of category theory.

A central concept is that of chain complexes, which can be studied through their homology and cohomology.

Homological algebra affords the means to extract information contained in these complexes and present it in the form of homological invariants of rings, modules, topological spaces, and other "tangible" mathematical objects.

K-theory is an independent discipline which draws upon methods of homological algebra, as does the noncommutative geometry of Alain Connes.

Homological algebra began to be studied in its most basic form in the late 19th century as a branch of topology and in the 1940s became an independent subject with the study of objects such as the ext functor and the tor functor, among others.

of abelian groups and group homomorphisms, with the property that the composition of any two consecutive maps is zero: The elements of Cn are called n-chains and the homomorphisms dn are called the boundary maps or differentials.

The chain groups Cn may be endowed with extra structure; for example, they may be vector spaces or modules over a fixed ring R. The differentials must preserve the extra structure if it exists; for example, they must be linear maps or homomorphisms of R-modules.

For example, if X is a topological space then the singular chains Cn(X) are formal linear combinations of continuous maps from the standard n-simplex into X; if K is a simplicial complex then the simplicial chains Cn(K) are formal linear combinations of the n-simplices of K; if A = F/R is a presentation of an abelian group A by generators and relations, where F is a free abelian group spanned by the generators and R is the subgroup of relations, then letting C1(A) = R, C0(A) = F, and Cn(A) = 0 for all other n defines a sequence of abelian groups.

In all these cases, there are natural differentials dn making Cn into a chain complex, whose homology reflects the structure of the topological space X, the simplicial complex K, or the abelian group A.

On a technical level, homological algebra provides the tools for manipulating complexes and extracting this information.

More generally, the notion of an exact sequence makes sense in any category with kernels and cokernels.

A short exact sequence of abelian groups may also be written as an exact sequence with five terms: where 0 represents the zero object, such as the trivial group or a zero-dimensional vector space.

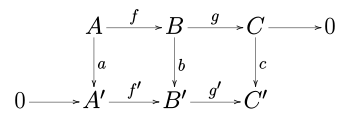

Then there is an exact sequence relating the kernels and cokernels of a, b, and c: Furthermore, if the morphism f is a monomorphism, then so is the morphism ker a → ker b, and if g' is an epimorphism, then so is coker b → coker c. In mathematics, an abelian category is a category in which morphisms and objects can be added and in which kernels and cokernels exist and have desirable properties.

Strictly speaking, this question is ill-posed, since there are always numerous different ways to continue a given exact sequence to the right.

The Ext functor is defined by This can be calculated by taking any injective resolution and computing Then (RnT)(B) is the cohomology of this complex.

For a fixed module B, this is a contravariant left exact functor, and thus we also have right derived functors RnG, and can define This can be calculated by choosing any projective resolution and proceeding dually by computing Then (RnG)(A) is the cohomology of this complex.

These two constructions turn out to yield isomorphic results, and so both may be used to calculate the Ext functor.

We set i.e., we take a projective resolution then remove the A term and tensor the projective resolution with B to get the complex (note that A⊗RB does not appear and the last arrow is just the zero map) and take the homology of this complex.

A continuous map of topological spaces gives rise to a homomorphism between their nth homology groups for all n. This basic fact of algebraic topology finds a natural explanation through certain properties of chain complexes.

for all n. A morphism F is called a quasi-isomorphism if it induces an isomorphism on the nth homology for all n. Many constructions of chain complexes arising in algebra and geometry, including singular homology, have the following functoriality property: if two objects X and Y are connected by a map f, then the associated chain complexes are connected by a morphism

are functorial as well, so that morphisms between algebraic or topological objects give rise to compatible maps between their homology.

The following definition arises from a typical situation in algebra and topology.

Cohomology theories have been defined for many different objects such as topological spaces, sheaves, groups, rings, Lie algebras, and C*-algebras.

The study of modern algebraic geometry would be almost unthinkable without sheaf cohomology.

Central to homological algebra is the notion of exact sequence; these can be used to perform actual calculations.

With a diverse set of applications in mind, it was natural to try to put the whole subject on a uniform basis.

An approximate history can be stated as follows: These move from computability to generality.

The computational sledgehammer par excellence is the spectral sequence; these are essential in the Cartan-Eilenberg and Tohoku approaches where they are needed, for instance, to compute the derived functors of a composition of two functors.

Spectral sequences are less essential in the derived category approach, but still play a role whenever concrete computations are necessary.