Homotherium

The first fossils of this genus were scientifically described in 1846 by Richard Owen as the species Machairodus latidens,[3] based on Pleistocene aged canine teeth found in Kent’s Cavern in Devon, England by the Reverend John MacEnery in 1826.

[4] The name Homotherium (Greek: ὁμός (homos, 'same') and θηρίον (therion, 'beast')) was proposed by Emilio Fabrini in 1890, without further explanation, for a new subgenus of Machairodus, whose main distinguishing feature was the presence of a large diastema between the two inferior premolars.

[7] In 1936, Teilhard de Chardin described the new species Homotherium ultimus based on fossils from the Middle Pleistocene-aged Zhoukoudian cave complex near Beijing in northern China.

Across time and space, the remains of H. latidens display considerable morphological variability, though there does not appear to be any clear pattern in this variation temporally or geographically (with the exception of the presence of "pocketing" of the margin of the masseteric fossa of the mandible appearing in Middle and Late Pleistocene H. latidens, but not earlier ones), with the morphological variation of the entire span of Homotherium in Eurasia from the Late Pliocene to the Late Pleistocene being similar to the variation found at the large sample for individuals from the Incarcal locality from the Early Pleistocene of Spain, supporting a single valid species.

[6] In 1972 the species Homotherium problematicum (originally Megantereon problematicus) was named based on fragmentary material from the Makapansgat locality in South Africa, of late Pliocene-Early Pleistocene age.

[18] A third species, Homotherium africanum (originally Machairodus africanus), has also been included based on remains found in Aïn Brimba, in Tunisia, North Africa,[19][20][21] dating to the early-middle Pliocene.

[22] In 1990, Alan Turner challenged the validity of H. problematicum and H. hadarensis, and later authors have generally refrained from referring African Homotherium fossils to any specific species due to their largely fragmentary nature.

[23] Homotherium first appeared during the Early Pliocene, about 4 million years ago, with its oldest remains being from the Odesa catacombs in Ukraine, and Koobi Fora in Kenya, which are close in age, making the origin location of the genus uncertain.

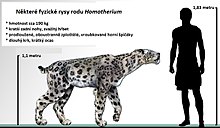

[46] Homotherium had shorter upper canine teeth than members of the machairodont tribe Smilodontini such as Smilodon or Megantereon, but these were still longer than those of extant cats.

[45] The joining region between the two halves of the lower jaw (mandibular symphysis) is angular and high, with the coronoid process of the mandible being relatively short.

Additionally, the cub had wide, rounded paws, which lacked a carpal pad, and its fur was dense: adaptations to traversing snowy terrain effectively, showcasing these features developed at a young age.

[45] The reduced claws, relatively slender and long limbs, and sloping back all appear to be adaptations for moderate speed endurance running in open habitats.

[49][45] The running-adapted morphology of its forelimbs suggests that they were less useful than those of Smilodon or many living big cats in grasping and restraining prey, and that instead the enlarged incisor teeth at the front of the jaws served this function, like in hyenas and canids.

Positive selection for genes related to vision indicates that sight probably played an important role in hunting, suggesting that Homotherium was a diurnal (day active) hunter.

[51] Isotopic analysis of H. latidens from the Venta Micena locality in southeast Spain dating to the Early Pleistocene, around 1.6 million years ago, suggests that at this locality H. latidens was the apex predator and hunted large prey in open habitats (likely including the equine Equus altidens, bison, as well as possibly juveniles of the mammoth Mammuthus meridionalis) and niche partitioned with the sabertooth Megantereon (a close relative of Smilodon) and the "European jaguar" Panthera gombaszoegensis, which hunted somewhat smaller prey in forested habitats.

[52] Analysis of specimens from Punta Lucero in northern Spain, dating to the early Middle Pleistocene (600-400,000 years ago), suggests that H. latidens at this locality exclusively consumed large (from 45 kilograms (99 lb) to over 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb)) prey, likely including aurochs, bison, red deer, and/or the giant deer Praemegaceros, and heavily overlapped in diet with the coexisting "European jaguar" Panthera gombaszoegensis.

[53] At the Friesenhahn Cave site in Texas, which dates to the Late Pleistocene (likely around 20-17,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum[47]), the remains of almost 400 juvenile Columbian mammoths were discovered along with numerous Homotherium serum skeletons of all ages, from elderly specimens to cubs.

[54] The sloped back and powerful lumbar section of Homotherium's vertebrae suggest that these animals could have been capable of pulling formidable loads; further, broken upper canines - a common injury in fossils of other machairodonts such as Machairodus and Smilodon that would have resulted from struggling with their prey - is not seen in Homotherium, perhaps because their social groups would completely restrain prey items before any of the cats attempted to kill the target with their saber teeth, or because the canines were less frail due to being covered.

[55] Isotopic analysis of H. serum dental remains at Friesenhahn Cave have confirmed that at this locality it predominantly fed on mammoths along with other C4 grazers, like bison and horses in open habitats, as well as possibly C4 browsers like the camel Camelops.

The seeming extinction of Homotherium latidens in Europe during the Middle Pleistocene may have been the result of competition with Homo heidelbergensis (in combination with the lion Panthera fossilis).