Horizontal gene transfer in evolution

HGT can also help scientists to reconstruct and date the tree of life, as a gene transfer can be used as a phylogenetic marker, or as the proof of contemporaneity of the donor and recipient organisms, and as a trace of extinct biodiversity.

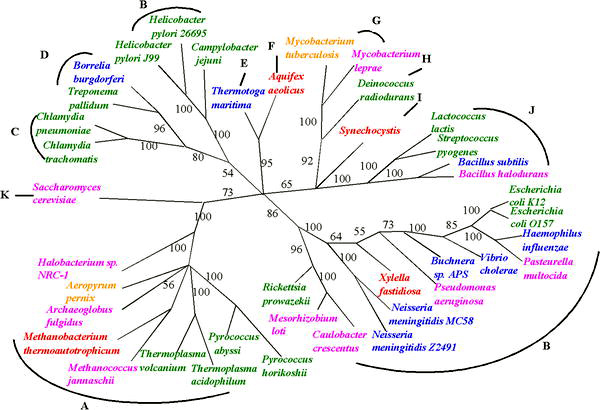

Recent discoveries of "rampant" HGT in microorganisms, and the detection of horizontal movement of even genes for the small subunit of ribosomal RNA, have forced biologists to question the accuracy of at least the early branches in the tree, and even question the validity of trees as useful models of how early evolution occurs.

[3] In fact, early evolution is considered to have occurred starting from a community of progenotes, able to exchange large molecules when HGT was the standard.

[4][5] "Sequence comparisons suggest recent horizontal transfer of many genes among diverse species including across the boundaries of phylogenetic "domains".

Only in later, multicellular eukaryotes do we know of definite restrictions on horizontal gene exchange, such as the advent of separated (and protected) germ cells...

But extensive transfer means that neither is the case: gene trees will differ (although many will have regions of similar topology) and there would never have been a single cell that could be called the last universal common ancestor..."[9] Doolittle suggested that the universal common ancestor cannot have been one particular organism, but must have been a loose, diverse conglomeration of primitive cells that evolved together.

[13] Jonathan Eisen and Claire Fraser have pointed out that: "In building the tree of life, analysis of whole genomes has begun to supplement, and in some cases to improve upon, studies previously done with one or a few genes.

For example, recent studies of complete bacterial genomes have suggested that the hyperthermophilic species are not deeply branching; if this is true, it casts doubt on the idea that the first forms of life were thermophiles.

Analysis of the genome of the eukaryotic parasite Encephalitozoon cuniculi supports suggestions that the group Microsporidia are not deep branching protists but are in fact members of the fungal kingdom.

This is the main conclusion of a 2005 study of more than 40 complete microbial genomic sequences by Fan Ge, Li-San Wang, and Junhyong Kim.

[3] Such a fusion of organisms hypothesis for the origin of complex nucleated cells has been put forward by Lynn Margulis using quite different reasoning about symbiosis between a bacterium and an archaen arising in an ancient consortium of microbes.