Carriage

They were generally owned by the rich, but second-hand private carriages became common public transport, the equivalent of modern cars used as taxis.

[1][failed verification] Used typically for warfare by Egyptians, the Near Easterners and Europeans, it was essentially a two-wheeled light basin carrying one or two standing passengers, drawn by one to two horses.

In 2021 archaeologists discovered the remains of a ceremonial four wheel carriage, a pilentum, near the ancient Roman city of Pompeii.

Sharing the traditional form of wheels and undercarriage known since the Bronze Age, it very likely also employed the pivoting fore-axle in continuity from the ancient world.

Historians also debate whether or not pageant wagons were built with pivotal axle systems, which allowed the wheels to turn.

[18][19] Suspension, whether on chains or leather, might provide a smoother ride since the carriage body no longer rested on the axles, but could not prevent swinging (branlant) in all directions.

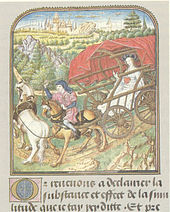

It is clear from illustrations (and surviving examples) that the medieval suspended carriage with a round tilt was a widespread European type, referred to by any number of names (car, currus, char, chariot).

They would have had four six-spoke six-foot high wheels that were linked by greased axles under the body of the coach, and did not necessarily have any suspension.

The chassis was made from oak beam and the barrel shaped roof was covered in brightly painted leather or cloth.

[21][22] The earliest illustrations of the Hungarian "Kochi-wagon" do not indicate any suspension, a body with high sides of lightweight wickerwork, and typically drawn by three horses in harness.

[23] The Hungarian coach spread across Europe, initially rather slowly, in part due to Ippolito d'Este of Ferrara (1479–1529), nephew of Mathias' queen Beatrix of Aragon, who as a very junior Archbishopric of Esztergom developed a taste for Hungarian riding and took his carriage and driver back to Italy.

[24] Then rather suddenly, in around 1550, the "coach" made its appearance throughout the major cities of Europe, and the new word entered the vocabulary of all their languages.

[25] However, the new "coach" seems to have been a fashionable concept (fast road travel for men) as much as any particular type of vehicle, and there is no obvious technological change that accompanied the innovation, either in the use of suspension (which came earlier), or the adoption of springs (which came later).

As its use spread throughout Europe in the late 16th century, the coach's body structure was ultimately changed, from a round-topped tilt to the "four-poster" carriages that became standard everywhere by c.1600.

It was only from the 18th century that changes to steering systems were suggested, including the use of the 'fifth wheel' substituted for the pivoting fore-axle, and on which the carriage turned.

Another proposal came from Erasmus Darwin, a young English doctor who was driving a carriage about 10,000 miles a year to visit patients all over England.

Early colonial horse tracks quickly grew into roads especially as the colonists extended their territories southwest.

The most complete working collection of carriages can be seen at the Royal Mews in London where a large selection of vehicles is in regular use.

Horses pulling a large carriage known as a "covered brake" collect the Yeoman of the Guard in their distinctive red uniforms from St James's Palace for Investitures at Buckingham Palace; High Commissioners or Ambassadors are driven to their audiences with the King and Queen in landaus; visiting heads of state are transported to and from official arrival ceremonies and members of the Royal Family are driven in Royal Mews coaches during Trooping the Colour, the Order of the Garter service at Windsor Castle and carriage processions at the beginning of each day of Royal Ascot.

[29] The top cover for the body of a carriage, called the head or hood, is often flexible and designed to be folded back when desired.

On the forepart of an open carriage, a screen of wood or leather called a dashboard intercepts water, mud or snow thrown up by the heels of the horses.

In some carriage types, the body is suspended from several leather straps called braces or thoroughbraces, attached to or serving as springs.

In some carriages a dropped axle, bent twice at a right angle near the ends, allows for a low body with large wheels.

The fore axletree and the splinter bar above it (supporting the springs) are united by a piece of wood or metal called a futchel, which forms a socket for the pole that extends from the front axle.

Originally, the word fittings referred to metal elements such as bolts and brackets, furnishings leaned more to leatherwork and upholstery or referred to metal buckles on harness, and appointments were things brought to a carriage but not part of it, however all of these words have blended together over time and are often used interchangeably to mean the smaller components or parts of a carriage or equipment.

A roofed structure that extends from the entrance of a building over an adjacent driveway and that shelters callers as they get in or out of their vehicles is known as a carriage porch or porte cochere.

A range of stables, usually with carriage houses (remises) and living quarters built around a yard, court or street, is called a mews.

Terminology varies: the simple, lightweight two- or four-wheeled show vehicle common in many nations is called a "cart" in the US, but a "carriage" in Australia.

Numerous varieties of horse-drawn carriages existed, Arthur Ingram's Horse Drawn Vehicles since 1760 in Colour lists 325 types with a short description of each.

By the early 19th century one's choice of carriage was only in part based on practicality and performance; it was also a status statement and subject to changing fashions.