Hours of Mary of Burgundy

[2] Its production began c. 1470, and includes miniatures by several artists, of which the foremost was the unidentified but influential illuminator known as the Master of Mary of Burgundy, who provides the book with its most meticulously detailed illustrations and borders.

Other miniatures, considered of an older tradition, were contributed by Simon Marmion, Willem Vrelant and Lieven van Lathem.

[3] Given the dark colourisation and mournful tone of the opening folios, the book may originally have been intended to mark the death of Mary's father, Charles the Bold, who died in 1477 at the Battle of Nancy.

Given their novel visual appeal, and the use of gold and silver leaf, they were more expensive and highly prized than more conventional books of hours, and produced for high-ranking members of the court of Philip the Good[b] and Charles the Bold.

Traditionally, pearls represent purity, and a transparent veil signifies virtue, while red carnations were often used as symbols of love.

[15] Evidence that it was commissioned for Mary include the feminine gender endings in some of the prayers and the recurring pairs of gold armorial shields throughout the book, indicating that it was prepared for an upcoming marriage.

Art historian Antoine De Schryver argues that this change of purpose and the pressure of completion for the wedding date of August 1477 explains why so many individual artists were involved.

[16] The Flemish artist Nicolas Spierinc, a favourite of the Burgundian court and Charles in particular,[17] has been identified as the chief scribe of the elegant and complex calligraphy.

[25] The margins on almost every page are decorated with drollerie consisting of flowers, insects, jewels and sibyls,[14] some of which were designed by Lieven van Lathem.

[26] It is because of these two miniatures that the Master is seen as the main innovator in bringing about a new style of Flemish illumination in the 1470s and 1480s,[29] earning him a great number of imitators.

[31] Mary of Burgundy can be identified as the woman in the foreground of folio 14v from the facial similarity to documented contemporary drawings and paintings.

Her finger traces the text of what seem to be the words Obsecro te Domina sancta maria ("I Beseech Thee, Holy Mary"), a popular prayer of indulgence in contemporary manuscript illuminations of donors venerating the Virgin and Child.

[38] The use of an open window was influenced by van Eyck's c. 1435 oil-on-panel painting the Madonna of Chancellor Rolin, where the pictorial space is divided into two areas; a foreground chiaroscuro interior which leads out, through arcades, to an expansive bright-lit exterior landscape.

[39] In the Vienna miniature, the artist achieves the transition from foreground to background by slowly diminishing the figures' scale and plasticity.

[26] The illustration has been compared in breadth of detail and style to van Eyck's Madonna in the Church, a small panel painting, which is yet twice the size of the Master's illumination.

[37] Folio 43v, Christ nailed to the Cross, shows a biblical scene viewed through the elaborately carved stone window of a contemporary late 15th century setting.

The artist employs a central axis and vanishing point to create an aerial perspective of sophistication previously unseen in northern illumination.

[26] The figure of Christ seems modeled on a similar painting of the Crucifixion attributed to Gerard David, now in the National Gallery, London.

[43] Nash suggests that this explains why a praying figure is absent from the room before the window – Mary is participating in the actual event.

[26] The influence of van der Goes can be seen in the modelling of St John, who closely resembles the same figure in the earlier artist's The Fall of Man and The Lamentation of 1470–75.

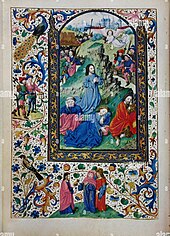

[28] The Crucifixion miniature, folio 99v, shows Christ and the two thieves raised on their crosses over a vast crowd which forms around them in a circular shape.

According to Kren, the image achieves its immediacy through the "numerous figures in motion — writhing, gesturing, stepping, or just listening with head attentively inclined".