Mary Magdalene

[29][23][24] Bruce Chilton, a scholar of early Christianity, states that the reference to the number of demons being "seven" may mean that Mary had to undergo seven exorcisms, probably over a long period of time, due to the first six being partially or wholly unsuccessful.

[52] He contends that the story of the empty tomb was invented by either the author of the Gospel of Mark or by one of his sources, based on the historically genuine fact that the women really had been present at Jesus's crucifixion and burial.

"[97] Mary defends herself, saying, "My master, I understand in my mind that I can come forward at any time to interpret what Pistis Sophia [a female deity] has said, but I am afraid of Peter, because he threatens me and hates our gender.

[136][8][137] In his anti-Christian polemic The True Word, written between 170 and 180, the pagan philosopher Celsus declared that Mary Magdalene was nothing more than "a hysterical female... who either dreamt in a certain state of mind and through wishful thinking had a hallucination due to some mistaken notion (an experience which has happened to thousands), or, which is more likely, wanted to impress others by telling this fantastic tale, and so by this cock-and-bull story to provide a chance for other beggars".

[144][145] Part of the reason for the identification of Mary Magdalene as a sinner may derive from the reputation of her birthplace, Magdala,[146] which, by the late first century, was infamous for its inhabitants' alleged vice and licentiousness.

[139] Elaborate medieval legends from Western Europe then emerged, which told exaggerated tales of Mary Magdalene's wealth and beauty, as well as of her alleged journey to southern Gaul (modern-day France).

[156] The aspect of the repentant sinner became almost equally significant as the disciple in her persona as depicted in Western art and religious literature, fitting well with the great importance of penitence in medieval theology.

[163] Not only John Chrysostom in the East (Matthew, Homily 88), but also Ambrose (De virginitate 3,14; 4,15) in the West, when speaking of Mary Magdalene after the resurrection of Jesus Christ, far from calling her a harlot, suggest she was a virgin.

[164] Starting in around the eighth century, Christian sources record mention of a church in Magdala purported to have been built on the site of Mary Magdalene's house, where Jesus exorcized her of the seven demons.

[167] Starting in early High Middle Ages, writers in western Europe began developing elaborate fictional biographies of Mary Magdalene's life, in which they heavily embellished upon the vague details given in the gospels.

[172] The theologian Honorius Augustodunensis (c. 1080 – c. 1151) embellished this tale even further, reporting that Mary was a wealthy noblewoman who was married in "Magdalum",[172] but that she committed adultery, so she fled to Jerusalem and became a "public sinner" (vulgaris meretrix).

[179] The most famous account of Mary Magdalene's legendary life comes from The Golden Legend, a collection of medieval saints' stories compiled circa 1260 by the Italian writer and Dominican friar Jacobus de Voragine (c. 1230 – 1298).

[181][177][182] In this account, Mary Magdalene is, in Ehrman's words, "fabulously rich, insanely beautiful, and outrageously sensual",[181] but she gives up her life of wealth and sin to become a devoted follower of Jesus.

"[196] A document, possibly written by Ermengaud of Béziers, undated and anonymous and attached to his Treatise against Heretics,[197] makes a similar statement:[198] Also they [the Cathars] teach in their secret meetings that Mary Magdalene was the wife of Christ.

[199]In the middle of the fourteenth century, a Dominican friar wrote a biography of Mary Magdalene in which he described her brutally mutilating herself after giving up prostitution,[193] clawing at her legs until they bled, tearing out clumps of her hair, and beating her face with her fists and her breasts with stones.

[164][202] In 1521, the theology faculty of the Sorbonne formally condemned the idea that the three women were separate people as heretical,[164][202] and debate died down, overtaken by the larger issues raised by Martin Luther.

[203] Luther, whose views on sexuality were much more liberal than those of his fellow reformers,[204] reportedly once joked to a group of friends that "even pious Christ himself" had committed adultery three times: once with Mary Magdalene, once with the Samaritan woman at the well, and once with the adulteress he had let off so easily.

[211] Anton Giulio Brignole-Sale's Maria Maddalena peccatrice convertita (1636) is considered one of the masterpieces of the 17th-century religious novel, depicting the Magdalen's tormented journey to repentance convincingly and with psychological subtlety.

[212] Estates of nobles and royalty in southern Germany were equipped with so-called "Magdalene cells", small, modest hermitages that functioned as both chapels and dwellings, where the nobility could retreat to find religious solace.

[215] Edgar Saltus's historical fiction novel Mary Magdalene: A Chronicle (1891) depicts her as a heroine living in a castle at Magdala, who moves to Rome becoming the "toast of the tetrarchy", telling John the Baptist she will "drink pearls... sup on peacock's tongues".

[228][223] Ki Longfellow's novel The Secret Magdalene (2005) draws on the Gnostic gospels and other sources to portray Mary as a brilliant and dynamic woman who studies at the fabled library of Alexandria, and shares her knowledge with Jesus.

[233] The film, which has been described as having a "strongly feminist bent",[232] was praised for its music score and cinematography,[234] its surprising faithfulness to the Biblical narrative,[232] and its acting,[232][231] but was criticized as slow-moving,[231][232][234] overwritten,[234] and too solemn to be believable.

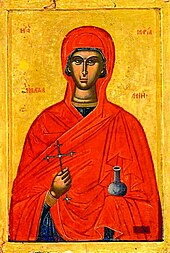

She may be shown either as very extravagantly and fashionably dressed, unlike other female figures wearing contemporary styles of clothes, or alternatively as completely naked but covered by very long blonde or reddish-blonde hair.

[240] Mary Magdalene at the foot of the cross during the Crucifixion appears in an eleventh-century English manuscript "as an expressional device rather than a historical motif", intended as "the expression of an emotional assimilation of the event, that leads the spectator to identify himself with the mourners".

As the swooning Virgin Mary became more common, generally occupying the attention of John, the unrestrained gestures of Magdalene increasingly represented the main display of the grief of the spectators.

One folk tradition concerning Mary Magdalene says that following the death and resurrection of Jesus, she used her position to gain an invitation to a banquet given by the Roman emperor Tiberius in Rome.

[272] The 1549 Book of Common Prayer had on July 22 a feast of Saint Mary Magdalene, with the same Scripture readings as in the Tridentine Mass and with a newly composed collect: "Merciful father geue us grace, that we neuer presume to synne through the example of anye creature, but if it shall chaunce vs at any tyme to offende thy dyuine maiestie: that then we maye truly repent, and lament the same, after the example of Mary Magdalene, and by lyuelye faythe obtayne remission of all oure sinnes: throughe the onely merites of thy sonne oure sauiour Christ."

[292] Many of the alleged relics of the saint are held in Catholic churches in France, especially at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume, where her skull (see above) and the noli me tangere are on display; the latter being a piece of forehead flesh and skin said to be from the spot touched by Jesus at the post-resurrection encounter in the garden.

[305][306] The Da Vinci Code also purports that the figure of the "beloved disciple" to Jesus's right in Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper is Mary Magdalene, disguised as one of the male disciples;[307] art historians maintain that the figure is, in reality, the apostle John, who only appears feminine due to Leonardo's characteristic fascination with blurring the lines between the sexes, a quality which is found in his other paintings, such as Saint John the Baptist (painted c. 1513 – 1516).

[310] Numerous works were written in response to the historical inaccuracies in The Da Vinci Code,[311][312] but the novel still exerted massive influence on how members of the general public viewed Mary Magdalene.