Household debt

Several economists have argued that lowering this debt is essential to economic recovery in the U.S. and selected Eurozone countries.

By some measures, consumers began to add certain types of debt again in 2012, a sign that the economy may be improving as this borrowing supports consumption.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported in April 2012: "Household debt soared in the years leading up to the Great Recession.

In advanced economies, during the five years preceding 2007, the ratio of household debt to income rose by an average of 39 percentage points, to 138 percent.

A surge in household debt to historic highs also occurred in emerging economies such as Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, and Lithuania.

This occurred largely because the central banks implemented a prolonged period of artificially low policy interest rates, temporarily increasing the amount of debt that could be serviced with a given income.

In short, the entire episode was straight out of Ludwig von Mises' 'Human Action', Chapter 20, with the new twist that most of the debt was incurred on the consumer side.

"Strategic defaults" became common, as homeowners with significant negative equity simply abandoned the home and the debt.

By the end of 2011, real house prices had fallen from their peak by about 41% in Ireland, 29% in Iceland, 23% in Spain and the United States, and 21% in Denmark.

Household defaults, underwater mortgages (where the loan balance exceeds the house value), foreclosures, and fire sales became endemic to a number of economies.

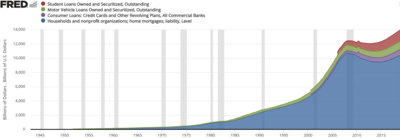

[10] U.S. household (HH) debt (measured by the FRED variable "CMDEBT")[12] rose relative to both GDP and disposable income over the 1980 to 2011 period.

[16] Paul Krugman wrote in December 2010: "The root of our current troubles lies in the debt American families ran up during the Bush-era housing bubble.

What we’ve been dealing with ever since is a painful process of 'deleveraging': highly indebted Americans not only can't spend the way they used to, they're having to pay down the debts they ran up in the bubble years.

"[17] In April 2009, U.S. Federal Reserve Vice Chair Janet Yellen discussed the situation: "Once this massive credit crunch hit, it didn’t take long before we were in a recession.

"[18] The policy prescription of Ms Yellen's predecessor Mr Bernanke was to increase the money supply and artificially reduce interest rates.

Mr Krugman's policy was to ensure that such borrowing took place at the federal government level, to be repaid via taxes on the individuals who he admitted were already overburdened with their own debts.

I’ve heard various economist make various smart points about why we should prefer one approach or the other, and it also happens to be the case that the two policies support each other and so we don't actually need to choose between them.

All of these solutions, of course, have drawbacks: if you put the government deeper into debt in order to help households now, you increase the risk of a public-debt crisis later.

If you force banks to swallow losses or face inflation now, you need to worry about whether they'll be able to keep lending at a pace that will support recovery over the next few years.

"[19] Economist Amir Sufi at the University of Chicago argued in July 2011 that a high level of household debt was holding back the U.S. economy.

He advocates mortgage write-downs and other debt-related solutions to re-invigorate the economy when household debt levels are exceptionally high.

[21] Rana Foroohar wrote in July 2012: "[R]esearch shows that the majority of job losses in the U.S. since the Great Recession were due to lower consumer spending because of household debt, a decline that resulted in layoffs at U.S. firms.

Some lenders may agree to write down mortgage values (reducing the homeowner's obligation) rather than taking even larger losses in foreclosure.

We have also written about plausible solutions that involve moderately higher inflation and “financial repression” — pushing down inflation-adjusted interest rates, which effectively amounts to a tax on bondholders.

[27] Professor Luigi Zingales (University of Chicago) advocated a mortgage debt for equity swap in July 2009, where the mortgage debt would be written down in exchange for the bank taking an interest in future appreciation of the home upon sale (a debt-for-equity swap).

[30][31] During the Great Depression, the U.S. created the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), which acquired and refinanced one million delinquent mortgages between 1933 and 1936.

This is the time dimension, which holds that the definition must capture persistent and ongoing financial problems and exclude one-off occurrences that arise due to forgetfulness, for instance.

An example of the last is the European Union's "Directive on Credit Agreements for Consumers Household debt advisory services".

Alleviative measures include debt advisory services, which aim to help households getting their finances back on track, mainly by means of information provision, budget planning and balancing, help with legal arrangements, negotiation with creditors, providing psychological support by having someone to talk to, and even by effectively, voluntarily taking over the managing of a household's finances.

During such procedures, the over-indebted household hands over all income above a minimum threshold to the creditors/state and is cleared of its debts after the period, varying in length from for example 1 year in the UK to 5 in Portugal and 12 in Ireland.