Heaving to

For a solo or shorthanded sailor it can provide time to go below deck, to attend to issues elsewhere on the boat or to take a meal break.

Therefore, unless other considerations dictate differently, it is helpful to heave to on the starboard tack, in order to be a "stand-on vessel", as per the regulations.

In what follows, the jibs and boomed sails on such craft can either be treated as one of each, or lowered for the purposes of reduced windage, heel or complexity when heaving to for any length of time.

Without the drive of the jib, and allowing time for momentum to die down, the sailboat will be unable to tack and will stop hove to.

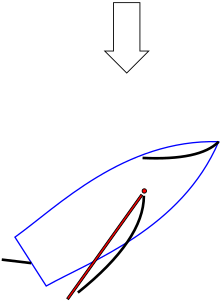

[12] Finally, in either case, the tiller or wheel should be lashed so that the rudder cannot move again, and the mainsheet adjusted so that the boat lies with the wind ahead of the beam with minimal speed forward.

Usually this involves easing the sheet slightly compared to a closehauled position, but depending on the relative sizes of the sails, the shape and configuration of the keel and rudder and the state of the wind and sea, each skipper will have to experiment.

To come out from the hove-to position and get under way again, the tiller or wheel is unlashed and the windward jibsheet is released, hauling in the normal leeward one.

[9] It is important when choosing the tack, heaving to, and remaining hove to, in a confined space that adequate room is allowed for these maneuvers.

[15] This included Sabre, a 10.4 m (34 ft) steel cutter with two persons on board, which hove to in wind speeds averaging 80 knots for 6 hours with virtually no damage.