Sailing

Large improvements in fuel economy allowed steam to progressively outcompete sail in, ultimately, all commercial situations, giving ship-owning investors a better return on capital.

Cruising can include extended offshore and ocean-crossing trips, coastal sailing within sight of land, and daysailing.

This greater mobility increased capacity for exploration, trade, transport, warfare, and fishing, especially when compared to overland options.

It has been estimated that it cost less for a sailing ship of the Roman Empire to carry grain the length of the Mediterranean than to move the same amount 15 miles by road.

2 [5]: 147 [b] A similar but more recent trade, in coal, was from the mines situated close to the River Tyne to London – which was already being carried out in the 14th century and grew as the city increased in size.

[7][c] The earliest image suggesting the use of sail on a boat may be on a piece of pottery from Mesopotamia, dated to the 6th millennium BCE.

Since there is no commonality between the boat technology of China and the Austronesians, these distinctive characteristics must have been developed at or some time after the beginning of the expansion.

[13] They traveled vast distances of open ocean in outrigger canoes using navigation methods such as stick charts.

[13] By the time of the Age of Discovery—starting in the 15th century—square-rigged, multi-masted vessels were the norm and were guided by navigation techniques that included the magnetic compass and making sightings of the sun and stars that allowed transoceanic voyages.

[16] During the Age of Discovery, sailing ships figured in European voyages around Africa to China and Japan; and across the Atlantic Ocean to North and South America.

Later, sailing ships ventured into the Arctic to explore northern sea routes and assess natural resources.

In the early 1800s, fast blockade-running schooners and brigantines—Baltimore Clippers—evolved into three-masted, typically ship-rigged sailing vessels with fine lines that enhanced speed, but lessened capacity for high-value cargo, like tea from China.

[17] Masts were as high as 100 feet (30 m) and were able to achieve speeds of 19 knots (35 km/h), allowing for passages of up to 465 nautical miles (861 km) per 24 hours.

Iron-hulled sailing ships were mainly built from the 1870s to 1900, when steamships began to outpace them economically because of their ability to keep a schedule regardless of the wind.

Even into the twentieth century, sailing ships could hold their own on transoceanic voyages such as Australia to Europe, since they did not require bunkerage for coal nor fresh water for steam, and they were faster than the early steamers, which usually could barely make 8 knots (15 km/h).

[21] Ultimately, the steamships' independence from the wind and their ability to take shorter routes, passing through the Suez and Panama Canals, made sailing ships uneconomical.

[33] Cruising on a sailing yacht may be either near-shore or passage-making out of sight of land and entails the use of sailboats that support sustained overnight use.

For craft with little forward resistance, such as ice boats and land yachts, this transition occurs further off the wind than for sailboats and sailing ships.

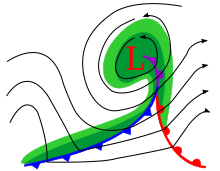

The higher the boat points to the wind under sail, the stronger the lateral force, which requires resistance from a keel or other underwater foils, including daggerboard, centerboard, skeg and rudder.

[49] If the desired course is within the no-go zone, then the sailing craft must follow a zig-zag route into the wind to reach its waypoint or destination.

[50] If the next waypoint or destination is within the arc defined by the no-go zone from the craft's current position, then it must perform a series of tacking maneuvers to get there on a zigzag route, called beating to windward.

However, some sailing craft such as iceboats, sand yachts, and some high-performance sailboats can achieve a higher downwind velocity made good by traveling on a series of broad reaches, punctuated by jibes in between.

A jib and mainsail are typically configured to be adjusted to create a smooth laminar flow, leading from one to the other in what is called the "slot effect".

[66] In addition to using the sheets to adjust the angle with respect to the apparent wind, other lines control the shape of the sail, notably the outhaul, halyard, boom vang and backstay.

A sailing vessel's form stability (derived from the shape of the hull and the position of the center of gravity) is the starting point for resisting heeling.

Additional measures for trimming a sailing craft to control heeling include:[61]: 131–5 The alignment of center of force of the sails with center of resistance of the hull and its appendices controls whether the craft will track straight with little steering input, or whether correction needs to be made to hold it away from turning into the wind (a weather helm) or turning away from the wind (a lee helm).

[61]: 131–5 Seamanship encompasses all aspects of taking a sailing vessel in and out of port, navigating it to its destination, and securing it at anchor or alongside a dock.

Depending on the alignment of the sail with the apparent wind (angle of attack), lift or drag may be the predominant propulsive component.

[45] Lift on a sail, acting as an airfoil, occurs in a direction perpendicular to the incident airstream (the apparent wind velocity for the headsail) and is a result of pressure differences between the windward and leeward surfaces and depends on the angle of attack, sail shape, air density, and speed of the apparent wind.

[84] Planing and foiling vessels are not limited by hull speed, as they rise out of the water without building a bow wave with the application of power.

A. Luffing ( no propulsive force ) — 0-30°

B. Close-hauled ( lift )— 30–50°

C. Beam reach ( lift )— 90°

D. Broad reach ( lift–drag )— ~135°

E. Running ( drag )— 180°

True wind ( V T ) is the same everywhere in the diagram, whereas boat velocity ( V B ) and apparent wind ( V A ) vary with point of sail.

2 –

staysail

2 –

staysail

3 –

spinnaker

3 –

spinnaker

4 – hull

5 –

keel

5 –

keel

6 –

rudder

6 –

rudder

7 –

skeg

7 –

skeg

8 – mast

9 –

spreader

9 –

spreader

10 –

shroud

10 –

shroud

11 – sheet

12 –

boom

12 –

boom

13 -

mast

13 -

mast

14 – spinnaker pole

15 –

backstay

15 –

backstay

16 – forestay

17 –

boom vang

17 –

boom vang

Left-hand boat : Down wind with detached airflow like a parachute — predominant drag component propels the boat with little heeling moment.

Right-hand boat : Up wind (close-hauled) with attached airflow like a wing —predominant lift component both propels the boat and contributes to heel.