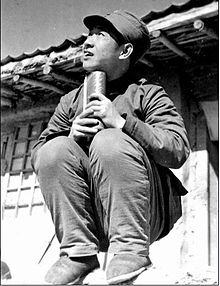

Hu Yaobang

After the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Hu rose to prominence as a close ally of Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader of China at the time.

After Deng rose to power, following Mao's death, Hu played an important role in the Boluan Fanzheng program.

The Chinese government subsequently censored details of Hu's life, but in 2005 it officially rehabilitated his image and lifted its censorships, on the occasion of his 90th birth anniversary.

However, a powerful local communist commander named Tan Yubao intervened at the last minute, saving Hu's life.

Hu became "number one" among the "Three Hus", whose names were vilified and who were paraded through Beijing wearing heavy wooden collars around their necks.

He also declared to cancel Bingtuan (soldier farmers) in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, but he failed to do so due to Wang Zhen's against.

[12] Hu traveled widely throughout his time as general secretary, visiting 1500 individual districts and villages in order to inspect the work of local officials and to keep in touch with the common people.

In 1971, Hu retraced the route of the Long March, and took the opportunity to visit and inspect remote military bases located in Tibet, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Yunnan, Qinghai, and Inner Mongolia.

On a trip to Inner Mongolia in 1984, Hu publicly suggested that Chinese people might start eating in a Western way (with forks and knives, on individual plates) in order to prevent communicable diseases.

[22] Hu was not prepared to abandon Marxism completely, but frankly expressed the opinion that Communism could not solve "all of mankind's problems".

Hu encouraged intellectuals to raise controversial subjects in the media, including democracy, human rights, and the possibility of introducing legal limits to the Communist Party's influence within the Chinese government.

[23] Hu alienated potential allies within the People's Liberation Army when he suggested for two consecutive years that the Chinese defense budget should be reduced, and senior military leaders began to criticize him.

When Hu visited Britain, military officials criticized him for drinking soup too loudly during a banquet hosted by Queen Elizabeth II.

[24] Zhao and Hu began a large-scale anti-corruption programme, and permitted the investigations of the children of high-ranking Party elders, who had grown up protected by their parents' influence.

During the event, which consisted of all of the Elders, Politburo, Secretariat, and the Central Advisory Commission, all of his allies abandoned him with the exception of his close friend, Xi Zhongxun, who stood up and defended him and lashed out at everybody for Hu's treatment.

"[27] After that, Hu became more reclusive and less active in Chinese politics, studying revolutionary history and practicing his calligraphy in his spare time, and taking long walks for exercise.

Among Chinese intellectuals Hu became an example of a man who refused to compromise his convictions in the face of political resistance, and who had paid the price as a result.

On 8 April 1989, Hu suffered a heart attack while attending a Politburo meeting in Zhongnanhai to discuss education reform.

[28] In his official obituary, Hu was described as "a long-tested and staunch communist warrior, a great proletarian revolutionist and statesman, an outstanding political leader for the Chinese army".

[13] Western reporters observed that Hu's obituary was intentionally "glowing" in order to divert suspicion that the Party had mistreated him.

"[29] Although he had become a semi-retired official by the time of his death, and had been removed from positions of real power for his "mistakes", public pressure forced the Chinese government to give him a state funeral, attended by Party leaders.

The eulogy at Hu's funeral praised his work in restoring political normality and promoting economic development after the Cultural Revolution.

[28] On 22 April 1989, 50,000 students marched to Tiananmen Square to participate in Hu's memorial service, and to deliver a letter of petition to Premier Li Peng.

The mourning became a public conduit for anger against perceived nepotism in the government, the unfair dismissal and early death of Hu, and the behind-the-scenes role of the "old men", officially retired leaders who nevertheless maintained quasi-legal power, such as Deng Xiaoping.

[32] Li Zhao collected money for the construction of Hu's tomb from both private and public sources; and, with the help of her son, they selected an appropriate location in Gongqingcheng.

Memorials with the purpose of recognizing the date of someone's birth or death are often signs of political trends within China, with some pointing to the prospect of further reform.

Around 350 people attended, including premier Wen Jiabao, vice president Zeng Qinghong, and numerous other Party officials, celebrities, and members of Hu Yaobang's family.

[38] Presented as an essay, it recollected an investigation of ordinary people's lives by Hu Yaobang and Wen Jiabao in Xingyi County, Guizhou, in 1986.

Wen's essay elicited an enthusiastic reaction in Chinese-language websites, generating over 20,000 responses on Sina.com on the day the article appeared.

[39] The article was interpreted by observers familiar with the Chinese political system as a confirmation by Wen that he was a protégé of Hu, rather than Zhao Ziyang.