Heian period

[2] The economy mostly existed through barter and trade due to the lack of a national currency, while the shōen system encouraged the growth of aristocratic estates that began gradually asserting their independence from Imperial control.

Despite a lack of serious warfare or domestic strife during the Heian era, crime and banditry were widespread as the Emperors failed to police the country effectively.

The period is also noted for the emergence of the samurai class, the result of feudal lords training their own warriors to police and enforce order as they gained land and resources through Imperial benefices.

To protect their interests in the provinces, nobles financed the training and arming of soldiers who in turn swore them allegiance rather than the Imperial court.

[2] As early as 939 AD, the warlord Taira no Masakado threatened the authority of the central government, leading an uprising in the eastern province of Hitachi, and almost simultaneously, Fujiwara no Sumitomo rebelled in the west; samurai played a crucial role in suppressing both disturbances on behalf of the Emperor.

At this time Taira no Kiyomori revived the Fujiwara practices by placing his grandson on the throne to rule Japan by regency.

Nara was abandoned after only 70 years in part due to the ascendancy of Dōkyō and the encroaching secular power of the Buddhist institutions there.

Kammu's avoidance of drastic reform decreased the intensity of political struggles, and he became recognized as one of Japan's most forceful emperors.

Although Kammu had abandoned universal conscription in 792, he still waged major military offensives to subjugate the Emishi, possible descendants of the displaced Jōmon, living in northern and eastern Japan.

After making temporary gains in 794, in 797, Kammu appointed a new commander, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, under the title Seii Taishōgun ("Barbarian-subduing generalissimo").

In the ninth and tenth centuries, much authority was lost to the great families, who disregarded the Chinese-style land and tax systems imposed by the government in Kyoto.

Central control of Japan had continued to decline, and the Fujiwara, along with other great families and religious foundations, acquired ever larger shōen and greater wealth during the early tenth century.

Three late-tenth-century and early-11th-century women presented their views of life and romance at the Heian court in Kagerō Nikki by "the mother of Fujiwara Michitsuna", The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon and The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu.

In time, large regional military families formed around members of the court aristocracy who had become prominent provincial figures.

Members of the Fujiwara, Taira, and Minamoto families—all of whom had descended from the imperial family—attacked one another, claimed control over vast tracts of conquered land, set up rival regimes, and generally upset the peace.

Go-Sanjo, determined to restore imperial control through strong personal rule, implemented reforms to curb Fujiwara influence.

While the Fujiwara fell into disputes among themselves and formed northern and southern factions, the insei system allowed the paternal line of the imperial family to gain influence over the throne.

Fujiwara no Yorinaga sided with the retired emperor in a violent battle in 1156 against the heir apparent, who was supported by the Taira and Minamoto (Hōgen Rebellion).

He gave his daughter Tokuko in marriage to the young emperor Takakura, who died at only 19, leaving their infant son Antoku to succeed to the throne.

Kiyomori filled no less than 50 government posts with his relatives, rebuilt the Inland Sea, and encouraged trade with Song China.

He also took aggressive actions to safeguard his power when necessary, including the removal and exile of 45 court officials and the razing of two troublesome temples, Todai-ji and Kofuku-ji.

The Taira were seduced by court life and ignored problems in the provinces,[citation needed] where the Minamoto clan were rebuilding their strength.

He appointed military governors, or shugo, to rule over the provinces, and stewards, or jito to supervise public and private estates.

[12] A close relationship developed between the Tendai monastery complex on Mount Hiei and the imperial court in its new capital at the foot of the mountain.

Both Kūkai and Saichō aimed to connect state and religion and establish support from the aristocracy, leading to the notion of "aristocratic Buddhism".

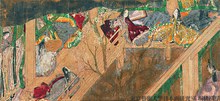

[14][15] Although written Chinese (kanbun) remained the official language of the Heian period imperial court, the introduction and widespread use of kana saw a boom in Japanese literature.

Despite the establishment of several new literary genres such as the novel and narrative monogatari (物語) and essays, literacy was only common among the court and Buddhist clergy.

The male courtly ideal included a faint mustache and thin goatee, while women's mouths were painted small and red, and their eyebrows were plucked or shaved and redrawn higher on the forehead (hikimayu).

Women cultivated shiny, black flowing hair and a courtly woman's formal dress included a complex "twelve-layered robe" called jūnihitoe, though the actual number of layers varied.

The shōen system enabled the accumulation of wealth by an aristocratic elite; the economic surplus can be linked to the cultural developments of the Heian period and the "pursuit of arts".