Hudson River Chains

Two other barriers across the river, referred to as chevaux-de-frise, were undertaken by the Colonials; the first, between Fort Washington on the island of Manhattan, and Fort Lee in New Jersey, was completed in 1776 and shortly seized by the British; another was started in 1776 between Plum Point on the east bank and Pollepel Island north of West Point but abandoned in 1777 in favor of completion of the Great Chain nearby the following year.

Even before the April 1775 Battles of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts, both the Americans and British knew that passage on the Hudson River was strategically important to each sides’ war effort.

[1] Colonial forces eventually constructed three obstacles across the river: a chevaux-de-frise at northern Manhattan between Forts Washington and Lee in 1776; at the lower entrance to the Hudson Highlands, from newly constructed Fort Montgomery on the west bank at Popolopen Creek just north of the modern-day Bear Mountain Bridge to Anthony's Nose on the east bank in 1776–1777; and between West Point and Constitution Island in 1778, known as the Great Chain.

Attention was concentrated on the West Point area because the river narrowed and curved so sharply there that ships slowed in navigating the passage by shifting winds, tides, and current made optimal targets.

Built to a design of Scottish engineer turned Colonial sympathizer Robert Erskine, the logs were intended to pierce and sink any British ships that passed over them.

This change had little impact, as the nascent Continental Navy lacked ships of the size and power of the British, leaving it to resort to small and more maneuverable vessels regardless.

Governor George Clinton, a member of the committee assigned by the New York Convention to devise a means of defending the Hudson, was heartened as the British had never attempted to run ships through the chain.

After Captain Machin recovered from wounds from battle with the British, he began work on the stronger Great Chain at West Point, which was constructed and installed in 1778.

A second log boom (resembling a ladder in construction) spanned the river about 100 yards (90 m) downstream to absorb the impact of any ship attempting to breach the barrier.

The Hudson River's changing tides, strong current, and frequently unfavorable winds created adverse sailing conditions at West Point.

A system of pulleys, rollers, ropes, and mid-stream anchors were used to adjust the chain's tension to overcome the effects of river current and changing tide.

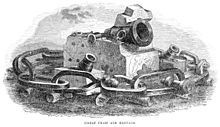

[8]: 52–70 After the war, part of the Great Chain was saved for posterity and the rest relegated to the West Point Foundry furnaces near Cold Spring, New York, to be melted down.

and log boom