Huemul Project

Richter was able to pitch the idea to President of Argentina Juan Perón in 1948, and soon received massive funding to build an experimental site on Huemul Island, on a lake just outside the town of San Carlos de Bariloche in Patagonia, near the Andes mountains.

On 24 March, the day before an important international meeting of the leaders of the Americas, Perón publicly announced that Richter had been successful, adding that in the future energy would be sold in packages the size of a milk bottle.

[2] According to Rainer Karlsch's Hitler's Bomb, during World War II German scientists under Walter Gerlach and Kurt Diebner carried out experiments to explore the possibility of inducing thermonuclear reactions in deuterium using high explosive-driven convergent shock waves, following Karl Gottfried Guderley's convergent shock wave solution.

At the same time, Richter proposed in a memorandum to German government officials the induction of nuclear fusion through shock waves by high-velocity particles shot into a highly compressed deuterium plasma contained in an ordinary uranium vessel.

In response, the Physical Association of Argentina (AFA) began to organize as a community to retain links between Argentine scientists, who now spread to industry.

[4] In 1946, the director of the AFA, physicist Enrique Gaviola, wrote a proposal to set up the Comisión Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas (National Scientific Research Commission), arguing that post-World War II friction (leading to the Cold War) would present the opportunity for various Northern Hemisphere scientists to move south to escape limits on their research.

In spite of the poor relations between the scientific community and the Argentine government, the proposal was seriously studied and Congress debated the matter on several occasions before Perón decided to place it under military control.

[5] By 1947, plans to form an atomic study group were progressing slowly when the entire issue was shut down by an article in the U.S. political newsmagazine, New Republic.

The 24 February 1947 issue contained an article by William Mizelle on "Peron's Atomic Plans", which claimed: With world famous German atom-splitter Werner Heisenberg invited to come to Argentina by Peron's Government and with a major uranium source discovered in Argentina, that Nation is launching a military nuclear research program to crack Pandora's box of atomic energy wide open.

[7] In 1947, a dossier was provided to Argentina by the Spanish embassy in Buenos Aires listing a number of German aeronautical engineers who were looking to sneak out of Germany.

[7] Ojeda and Tank communicated and formulated plans to begin building a jet fighter in Argentina, which would eventually emerge as the FMA IAe 33 Pulqui II.

Tank set up an aircraft development plant in Córdoba, and continued to contact other German engineers and scientists who might be interested in joining them.

Perón was intrigued, and clearly impressed, later telling reporters that "in half an hour he explained to me all the secrets of nuclear physics and he did it so well that now I have a pretty good idea of the subject".

"[13] Other German scientists, including Guido Beck, Walter Seelmann-Eggbert, and the now-elderly Richard Gans quickly realized something was amiss in the entire affair, and began to align themselves with the AFA, steering clear of Richter and the government in general.

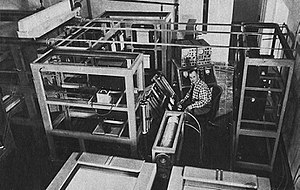

González selected a location deep within the country's interior on Huemul Island, in Nahuel Huapi Lake, where it would be easy to protect from prying eyes.

[8] In May 1950, Perón formed the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA), bypassing Gaviola's earlier efforts and placing himself in the position of president, with Richter and the minister of technical affairs as the other chairs.

[15] A year later, he formed the National Atomic Energy Directorate (DNEA), under González, to provide project assistance and logistics support.

[17] On 23 February, a technician working for the project expressed his concerns about the claims, suggesting that the measurement was likely due to the accidental tilting of the spectrograph's photographic plate while the experimental run was being set up.

This led to harsh criticism in the U.S. Miller suggested a policy of "masterful inaction", not actively denying support for the project, but simply never providing any.

On 24 March, Perón held a press conference at Casa Rosada and stated that: On February 16, 1951, in the atomic energy pilot plant on Huemul Island... thermonuclear experiments were carried out under conditions of control on a technical scale.

[1] He went on to note that the country was simply unable to afford the cost of developing a uranium-based energy program, or that of a system using tritium, normally generated in special fission plants.

Richter's fuel meant the reaction could only take place in a reactor, not a bomb, and he then recommitted the country to exploring only peaceful uses of atomic energy.

Very little explanation of the Thermotron was mentioned, beyond the announcement that he used the Doppler effect to measure speeds of 3,300 km/s and that the fuel was either lithium hydride or deuterium which was introduced into pre-heated hydrogen.

[28] George Thomson, at that time leading the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (AEA), suggested it was simply exaggerated.

[29] In May, the United Nations World magazine carried a short article by Hans Thirring, the director of the Institute for Theoretical Physics in Vienna and a well known author on nuclear matters.

Spitzer was able to use the notoriety surrounding Richter's announcement to gain the attention of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission with the suggestion that the basic idea of controlled fusion was feasible.

Small experimental devices had been built at the Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE, "Harwell") and Imperial College London, but requests for funding of a larger system were repeatedly refused.

When news of ZETA was made public, the U.S. and Soviet Union were soon demanding funding to build devices of similar scale in order to catch up with the UK.

[38] Instead of calling upon the local physics community, Perón put together a team consisting of Iraolagoitía, a priest, two engineers including Mario Báncora, and young physicist José Antonio Balseiro, who was at that time studying in England and was asked to return with all haste.

[1] In the period immediately after the military takeover, Balseiro wrote a proposal to create a nuclear physics institute on the mainland in nearby Bariloche using the equipment on the island.