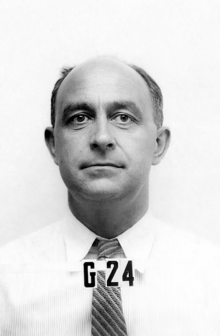

Enrico Fermi

Fermi did important work in particle physics, especially related to pions and muons, and he speculated that cosmic rays arose when the material was accelerated by magnetic fields in interstellar space.

Written in Latin by Jesuit Father Andrea Caraffa [it], a professor at the Collegio Romano, it presented mathematics, classical mechanics, astronomy, optics, and acoustics as they were understood at the time of its 1840 publication.

At Amidei's urging, Fermi learned German to be able to read the many scientific papers that were published in that language at the time, and he applied to the Scuola Normale Superiore in Pisa.

[23] That year, Fermi submitted his article "On the phenomena occurring near a world line" (Sopra i fenomeni che avvengono in vicinanza di una linea oraria) to the Italian journal I Rendiconti dell'Accademia dei Lincei [it].

[24][25] Fermi submitted his thesis, "A theorem on probability and some of its applications" (Un teorema di calcolo delle probabilità ed alcune sue applicazioni), to the Scuola Normale Superiore in July 1922, and received his laurea at the unusually young age of 20.

Fermi then studied in Leiden with Paul Ehrenfest from September to December 1924 on a fellowship from the Rockefeller Foundation obtained through the intercession of the mathematician Vito Volterra.

From January 1925 to late 1926, Fermi taught mathematical physics and theoretical mechanics at the University of Florence, where he teamed up with Rasetti to conduct a series of experiments on the effects of magnetic fields on mercury vapour.

In 1928, he published his Introduction to Atomic Physics (Introduzione alla fisica atomica), which provided Italian university students with an up-to-date and accessible text.

Fermi also conducted public lectures and wrote popular articles for scientists and teachers in order to spread knowledge of the new physics as widely as possible.

In the introduction to the 1968 English translation, physicist Fred L. Wilson noted that:Fermi's theory, aside from bolstering Pauli's proposal of the neutrino, has a special significance in the history of modern physics.

[55][56] Fermi had the idea to resort to replacing the polonium-beryllium neutron source with a radon-beryllium one, which he created by filling a glass bulb with beryllium powder, evacuating the air, and then adding 50 mCi of radon gas, supplied by Giulio Cesare Trabacchi [it].

[66] After Fermi received the prize in Stockholm, he did not return home to Italy but rather continued to New York City with his family in December 1938, where they applied for permanent residency.

On 25 January 1939, in the basement of Pupin Hall at Columbia, an experimental team including Fermi conducted the first nuclear fission experiment in the United States.

[80][81] Leó Szilárd obtained 200 kilograms (440 lb) of uranium oxide from Canadian radium producer Eldorado Gold Mines Limited, allowing Fermi and Anderson to conduct experiments with fission on a much larger scale.

[85] Later that year, Szilárd, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller sent the letter signed by Einstein to US president Franklin D. Roosevelt, warning that Nazi Germany was likely to build an atomic bomb.

[89] The S-1 Section of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, as the Advisory Committee on Uranium was now known, met on 18 December 1941, with the US now engaged in World War II, making its work urgent.

Then, half apologetically, because I had led the S-l Committee to believe that it would be another week or more before the pile could be completed, I added, "the earth was not as large as he had estimated, and he arrived at the new world sooner than he had expected."

Fermi was recommended by colleague Emilio Segrè to ask Chien-Shiung Wu, as she prepared a printed draft on this topic to be published by the Physical Review.

The scientists had originally considered this over-engineering a waste of time and money, but Fermi realized that if all 2,004 tubes were loaded, the reactor could reach the required power level and efficiently produce plutonium.

James B. Conant and Leslie Groves were also briefed, but Oppenheimer wanted to proceed with the plan only if enough food could be contaminated with the weapon to kill half a million people.

[107] Arriving in September, Fermi was appointed an associate director of the laboratory, with broad responsibility for nuclear and theoretical physics, and was placed in charge of F Division, which was named after him.

[108] Fermi observed the Trinity test on 16 July 1945 and conducted an experiment to estimate the bomb's yield by dropping strips of paper into the blast wave.

[110] Like others at the Los Alamos Laboratory, Fermi found out about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki from the public address system in the technical area.

[111] Fermi became the Charles H. Swift Distinguished Professor of Physics at the University of Chicago on 1 July 1945,[112] although he did not depart the Los Alamos Laboratory with his family until 31 December 1945.

[119] He also liked to spend a few weeks each year at the Los Alamos National Laboratory,[120] where he collaborated with Nicholas Metropolis,[121] and with John von Neumann on Rayleigh–Taylor instability, the science of what occurs at the border between two fluids of different densities.

His PhD students in the postwar period included Owen Chamberlain, Geoffrey Chew, Jerome Friedman, Marvin Goldberger, Tsung-Dao Lee, Arthur Rosenfeld and Sam Treiman.

The history of science and technology has consistently taught us that scientific advances in basic understanding have sooner or later led to technical and industrial applications that have revolutionized our way of life.

[135] A memorial service was held at the University of Chicago chapel, where colleagues Samuel K. Allison, Emilio Segrè, and Herbert L. Anderson spoke to mourn the loss of one of the world's "most brilliant and productive physicists.

These include the Fermilab particle accelerator and physics lab in Batavia, Illinois, which was renamed in his honour in 1974,[151] and the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, which was named after him in 2008, in recognition of his work on cosmic rays.

[154] A synthetic element isolated from the debris of the 1952 Ivy Mike nuclear test was named fermium, in honor of Fermi's contributions to the scientific community.