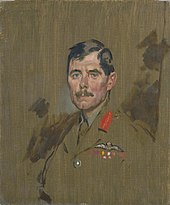

Hugh Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard

After the end of the Boer War, Trenchard saw service in Nigeria where he was involved in efforts to bring the interior under settled British rule and quell intertribal violence.

[6] The country setting meant that he could enjoy an outdoor life, including spending time hunting rabbits and other small animals with the rifle he was given on his eighth birthday.

His requests were rejected by his colonel, and when the Viceroy Lord Curzon, who was concerned about the drain of leaders to South Africa, banned the dispatch of any further officers, Trenchard's prospects for seeing action looked bleak.

However, a year or two previously, it had so happened that he had been promised help or advice from Sir Edmond Elles, as a gesture of thanks after rescuing a poorly planned rifle-shooting contest from disaster.

Part of the newly formed company consisted of a group of volunteer Australian horsemen who, thus far being under-employed, had largely been noticed for excessive drinking, gambling and debauchery.

Kitchener had received intelligence on their location and he hoped to damage the morale of Boer commandos at large by sending a small group of men to capture their political leadership.

Finding peace-time regimental life dull, he sought to expand his area of responsibility by attempting to reorganise his fellow officers' administrative procedures, which they resented.

[45] He also clashed with Colonel Stuart, his commanding officer, who told him that the town was too small for both of them,[46] and by February 1912 had resorted to applying for employment with various colonial defence forces, without success.

[62] With the outbreak of First World War, Trenchard was appointed Officer Commanding the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, replacing Lieutenant-Colonel Sykes.

[76] Prior to the British First Army's offensives at Ypres and Aubers Ridge in April and May, the First Wing's crews flew reconnaissance sorties using aerial cameras over the German lines.

Trenchard defended in the debate Haig's policy of constant attacks on the Western Front, arguing that it had been preferable to standing on the defensive, and he himself also had maintained an offensive posture throughout the war which, like the infantry, had resulted in the Flying Corps taking extremely heavy casualties.

[87] Finally and most significantly, they disagreed over proper future use of air power which Trenchard judged as being vital in preventing a repeat of the strategic stalemate which had occurred along the Western Front.

[88] Also during this period Trenchard resisted pressure from several press barons to support an "air warfare scheme", which would have seen the British armies withdrawn from France and an attempt to defeat Germany entrusted to the R.A.F.

However, as the weeks went on they became increasingly estranged personally, and a low point was reached in mid-March when Trenchard discovered that Rothermere had promised the Navy 4000 aircraft for anti-submarine duties.

The new Air Minister, Sir William Weir, under pressure to find a position for Trenchard, offered him command of the yet to be formed Independent Force, which was to conduct long-range bombing operations against Germany.

[94] Trenchard rejected the offer of a proposed new post which would have meant a London-based command of the bombing operations conducted from Ochey, arguing that the responsibility was Newall's under the direction of Salmond.

[98] The Independent Air Force continued the task of the VIII Brigade from which it was formed, carrying out strategic bombing attacks on German railways, airfields and industrial centres.

[99] Initially, the French general Ferdinand Foch, as the newly appointed Supreme Allied Commander, refused to recognize the Independent Air Force, which caused some logistical difficulties.

The problems were resolved after a meeting of Trenchard and General de Castelnau, who disregarded the concerns about the status of the Independent Air Force and did not block the much-needed supplies.

[100] In September 1918, Trenchard's Force indirectly supported the American Air Service during the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, attacking German airfields in that sector of the front, along with supply depots and rail lines.

[101] Trenchard's close co-operation with the Americans and the French was formalized when his command was redesignated the Inter-Allied Independent Air Force in late October 1918, and placed directly under the orders of Foch.

's inactive list,[105] Trenchard returned to military duties in mid-January 1919, when Sir William Robertson, the Commander-in-Chief of Home Forces, asked him to get control of around 5000 mutinying soldiers at Southampton Docks, who were protesting about being sent to France with the war being over.

After Churchill indicated that Sykes might be appointed Controller of Civil Aviation and made a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire, Trenchard agreed to consider the offer.

In early 1920 he suggested that it could even be used to violently suppress if necessary "industrial disturbances, or risings" in the United Kingdom itself, following on from his experience in such matters in successfully quelling the troop mutiny at Southampton Docks in the previous year.

[133] The following year he began to feel that he had achieved all he could as Chief of the Air Staff and that he should give way to a younger man, and he offered his resignation to the Cabinet in late 1928, although it was not initially accepted.

[134] Around the same time as Trenchard was considering his future the British Legation and some European diplomatic staff based in Kabul were cut off from the outside world as a result of the civil war in Afghanistan.

As an ardent supporter of the bomber, Trenchard found much to disagree with in the air expansion programme, its emphasis on defensive fighter aircraft, and he wrote about it directly to the Cabinet.

Towards the end of the month Churchill offered him a job that would have seen him acting as a general officer commanding all British land, air and sea forces at home should an invasion occur.

Acting with Sir John Salmond he quietly but successfully lobbied for the removal of Newall as Chief of the Air Staff and Dowding as the Command-in-Chief of Fighter Command.

[168] In the aftermath of the war, several American generals, including Henry H. Arnold and Carl Andrew Spaatz, asked Trenchard to brief them in connection with the debate which surrounded the proposed establishment of the independent United States Air Force.