Trebuchet

This is an accepted version of this page A trebuchet[nb 1] (French: trébuchet) is a type of catapult[5] that uses a rotating arm with a sling attached to the tip to launch a projectile.

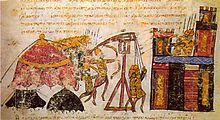

It spread westward, possibly by the Avars, and was adopted by the Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, and other neighboring peoples by the sixth to seventh centuries AD.

The difficulties of coordinating the pull of many men together repeatedly and predictably makes counterweight trebuchets preferable for the larger machines, though they are more complicated to engineer.

This is unlike the violent sudden stop inherent in the action of other catapult designs such as the onager, which must absorb most of the launching energy into their own frame, and must be heavily built and reinforced as a result.

When attempting to breach enemy walls, it is important to use materials that will not shatter on impact; projectiles were sometimes brought from distant quarries to get the desired properties.

They were used as defensive weapons stationed on walls and sometimes hurled hollowed-out logs filled with burning charcoal to destroy enemy siege works.

[37][38] By the 1st century AD, commentators were interpreting other passages in texts such as the Zuo zhuan and Classic of Poetry as references to the traction trebuchet: "the guai is 'a great arm of wood on which a stone is laid, and this by means of a device [ji] is shot off and so strikes down the enemy.

According to a stele in Barkul celebrating Tang Taizong's conquest of what is now Ejin Banner, the engineer Jiang Xingben made great advancements on trebuchets that were unknown in ancient times.

[44]The traction trebuchet was adopted by various peoples west of China such as the Byzantines, Persians, Arabs, and Avars by the sixth to seventh centuries AD.

Regardless of the vector of transmission, it appeared in the eastern Mediterranean by the late 6th century AD, where it replaced torsion powered siege engines such as the ballista and onager.

It was probably also safer than the twisted cords of torsion weapons, "whose bundles of taut sinews stored up huge amounts of energy even in resting state and were prone to catastrophic failure when in use.

"[47][48][49][50] At the same time, the late Roman Empire seems to have fielded "considerably less artillery than its forebears, organised now in separate units, so the weaponry that came into the hands of successor states might have been limited in quantity.

Most accounts of traction trebuchets describe them as light artillery weapons while actual penetration of defenses was the result of mining or siege towers.

"[61] During the siege of Baghdad in 865, defensive artillery were responsible for repelling an attack on the city gate while traction trebuchets on boats claimed a hundred of the defenders' lives.

In 1090, Khalaf ibn Mula'ib threw out a man from the citadel in Salamiya with a machine and in the early 12th century, Muslim siege engines were able to breach crusader fortifications.

[80] At the siege of Nicaea in 1097 the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos reportedly invented new pieces of heavy artillery which deviated from the conventional design and made a deep impression on everyone.

[99] On the side of caution, historians such as John France, Christopher Marshall, and Michael Fulton emphasize the still considerable difficulty of reducing fortifications with siege artillery.

"[101] Reservations on the counterweight trebuchet's destructive capability were expressed by Viollet-le-Duc, who "asserted that even counterweight-powered artillery could do little more than destroy crenellations, clear defenders from parapets and target the machines of the besieged.

"[102] In spite of the evidence regarding increasingly powerful counterweight trebuchets during the 13th century, "it remains an important consideration that not one of these appears to have effected a breach that directly led to the fall of a stronghold.

"[103] In 1220, Al-Mu'azzam Isa laid siege to Atlit with a trabuculus, three petrariae, and four mangonelli but could not penetrate past the outer wall, which was soft but thick.

[106] Though stone projectiles of substantial size (~66 kilograms (146 lb)) have been found at Acre, located near the site of the siege and likely used by the Mamluks, surviving walls of a 13th-century Montmusard tower are no more than one meter thick.

Ropes of rice straw four inches thick and thirty-four feet long were joined together twenty at a time, draped on to the buildings from top to bottom, and covered with [wet] clay.

During an assault on Muntcada by King James I, a trebuchet was used to target a tower, destroying the structure and causing the consequential deaths of civilians and livestock.

[116] But typically the counterweight trebuchet was used against battlements such as parapets, other defensive structures, and the lower section of walls due to its greater accuracy and longer range, which was how it was employed by the Kingdom of Aragon.

Their slower shooting rate and greater mass made them more difficult to reposition, or even yaw, leaving few incentives to employ a small counterweight engine rather than a comparable traction type.

According to Liang Jieming, the "illustration shows ... its throwing arm disassembled, its counterweight locked with supporting braces, and prepped for transport and not in battle deployment.

The trebuchet gained significant interest from numerous news sources when in 2015 a burning missile fired from the siege engine struck and damaged a Victorian-era boathouse situated at the River Avon close by, inadvertently demonstrating the weapon's power.

[144][145] In the episode "Carnage A Trois" in series 4 of The Grand Tour the presenters uses a trebuchet to allegedly sling a Citroën C3 Pluriel from the White Cliffs of Dover across the English Channel.

[146][147] The Stamford based YouTube personality and inventor Colin Furze created a 14-metre (46 ft) high trebuchet capable of throwing a washing machine in December 2020.

[150][better source needed] Instead of using the traditional axle fixed to a frame, these devices are mounted on wheels that roll on a track parallel to the ground, with a counterweight that falls directly downward upon release, allowing for greater efficiency by increasing the proportion of energy transferred to the projectile.