Torsion mangonel myth

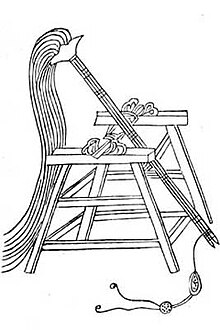

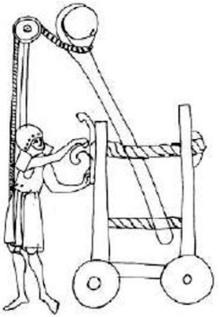

In reality, the vast body of contemporary evidence in art and documents point to the mangonel being a machine operated on manpower-pulling cords attached to a lever and sling to launch projectiles.

"[5] The torsion mangonel myth began in the 18th century when Francis Grose claimed that the onager was the dominant medieval artillery until the arrival of gunpowder.

Cathcart King, Jim Bradbury, Christopher Marshall, and David Bachrach disagreed and argued that torsion machines were used throughout the Middle Ages.

"[13] The idea of a torsion powered mangonel is particularly appealing for many historians due to its potential as an argument for the continuity of classical technologies and scientific knowledge into the Early Middle Ages, which they use to refute the concept of medieval decline.

Tarver considered the traction powered machines to have provided a viable alternative to the "onager soon after the collapse of the Roman Empire and long before the introduction of the counterweight trebuchet in the 12th century.

"[6] In 1997, Randall Rogers deemed it relatively certain that two-armed stone throwing machines (ballistas) were not used during medieval times, and although it is difficult to prove that one-armed ones (onagers) were not, he could not find any evidence that they were.

[24] In 2018, Michael S. Fulton noted that there is "insufficient evidence at this time to conclusively prove or disprove that the use of torsion stone-throwers continued through the Middle Ages,"[25] but traction trebuchets appear to have been the most common, or only, mechanical stone thrower during the First Crusade.

"[27] By the 9th century, when the first Western European reference to a mangana (mangonel) appeared, there is virtually no evidence at all, whether textual or artistic, of torsion engines used in warfare.

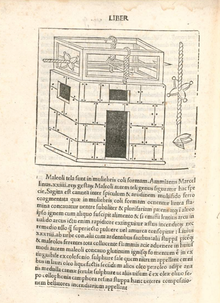

Fulton notes that the engine appears oddly shaped, impractical, and likely based on the illustrator's interpretation of an onager derived from classical descriptions.

... anyone consulting Bradbury's Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare (2004) will find mangonels described as stone-throwing catapults powered by the torsion effect of twisted ropes...

In all this mass of illustrations, there are numerous depictions of manually operated stone throwers, then of trebuchets and, finally, of bombards and other types of weapon and siege equipment.

Taking into consideration the constraints under which the monastic artists were working, and their purpose (which was not, of course, to provide a scientifically precise depiction of a particular siege), such illustrations are often remarkably accurate.

Torsion power went out of use for some seven centuries before returning in the guise of the bolt-throwing springald, deployed not as an offensive, wallbreaking siege engine, but to defend those walls against human assailants.

Writing in the late 9th century, Abbo Cernuus described mangana throwing large stones while catapultae threw pots of melted lead.

Abbo also mentioned catapultae mounted on city walls, which Bachrach interpreted as a function of their smaller size, and thus proof that they were torsion stone throwers, while the mangana were larger traction trebuchets that had to be positioned on the ground.

[42] As for the springald, it was a defensive torsion bolt thrower based on the design of ancient ballistas, with two arms held in a skein of twisted sinew or hair.

Springalds were commonly used to defend gates from atop towers, where their skeins were safe from wet weather and their bolts could be shot a greater distance.

[43] Springalds were expensive to produce: Liebel's calculation for the cost of machines built for the pope at Avignon puts them at six months' worth of wages for an unskilled laborer.

[44] John France suggests that different terms for siege engines such as petraria, mangana, mangonella, and tortentum referred to size categories instead.

According to Bachrach, this meant mangana were traction trebuchets because of their greater size while catapultae were torsion machines because they were stationed on city walls, and thus smaller.

William of Tyre mentioned the use of machinae during the Siege of Jerusalem (1099), but this was translated as perriers and mangoniaux in the later Estoire d'Eracles, and as petrariae and trebuculi by Roger of Wendover.