Human impact on the nitrogen cycle

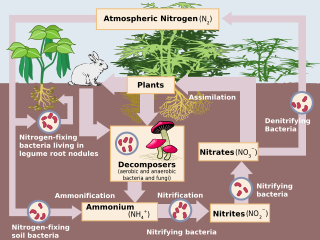

[1] Utilizing a large amount of metabolic energy and the enzyme nitrogenase, some bacteria and cyanobacteria convert atmospheric N2 to NH3, a process known as biological nitrogen fixation (BNF).

[5] Near the turn of the century, Nr from guano and sodium nitrate deposits was harvested and exported from the arid Pacific islands and South American deserts.

Since the Industrial Revolution, an additional source of anthropogenic N input has been fossil fuel combustion, which is used to release energy (e.g., to power automobiles).

[4] NOx produced by industrial processes, automobiles and agricultural fertilization and NH3 emitted from soils (i.e., as an additional byproduct of nitrification)[4] and livestock operations are transported to downwind ecosystems, influencing N cycling and nutrient losses.

[1] Atmospheric Nr species can be deposited to ecosystems in precipitation (e.g., NO3−, NH4+, organic N compounds), as gases (e.g., NH3 and gaseous nitric acid [HNO3]), or as aerosols (e.g., ammonium nitrate [NH4NO3]).

In highly developed areas of near shore coastal ocean and estuarine systems, rivers deliver direct (e.g., surface runoff) and indirect (e.g., groundwater contamination) N inputs from agroecosystems.

[4] In acid soils, mobilized aluminium ions can reach toxic concentrations, negatively affecting both terrestrial and adjacent aquatic ecosystems.

[15] A potential concern of increased N deposition due to human activities is altered nutrient cycling in forest ecosystems.

[17] In systems with high uptake, N is assimilated into the plant biomass, leading to enhanced net primary productivity (NPP) and possibly increased carbon sequestration through greater photosynthetic capacity.

[12][17][18] N saturation can result in nutrient imbalances (e.g., loss of calcium due to nitrate leaching) and possible forest decline.

It found that chronic N additions resulted in greater leaching losses, increased pine mortality, and cessation of biomass accumulation.

[18] Another study reported that chronic N additions resulted in accumulation of non-photosynthetic N and subsequently reduced photosynthetic capacity, supposedly leading to severe carbon stress and mortality.

[21] In patch-based systems, regional coexistence can occur through tradeoffs in competitive and colonizing abilities given sufficiently high disturbance rates.

However, as demonstrated by Wilson and Tilman, increased nutrient inputs can negate tradeoffs, resulting in competitive exclusion of these superior colonizers/poor competitors.

[8] Atmospheric N deposition in terrestrial landscapes can be transformed through soil microbial processes to biologically available nitrogen, which can result in surface-water acidification, and loss of biodiversity.

[29] Reactive nitrogen from agriculture, animal-raising, fertilizer, septic systems, and other sources have raised nitrate concentrations in waterways of most industrialized nations.

In the United States alone, as much as 20% of groundwater sources exceed the World Health Organization's limit of nitrate concentration in potable water.

[30] Urbanization, deforestation, and agricultural activities largely contribute sediment and nutrient inputs to coastal waters via rivers.

[1][34] Most Nr applied to global agroecosystems cascades through the atmosphere and aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems until it is converted to N2, primarily through denitrification.

[34] Many studies have clearly demonstrated that managed buffer strips and wetlands can remove significant amounts of nitrate (NO3−) from agricultural systems through denitrification.

[36] N inputs have shown negative consequences for both nutrient cycling and native species diversity in terrestrial and aquatic systems.

In fact, due to long-term impacts on food webs, Nr inputs are widely considered the most critical pollution problem in marine systems.

[8] In both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, responses to N enrichment vary; however, a general re-occurring theme is the importance of thresholds (e.g., nitrogen saturation) in system nutrient retention capacity.