Hume's fork

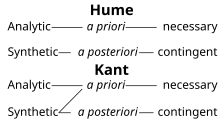

)[3] As phrased in Immanuel Kant's 1780s characterization of Hume's thesis, and furthered in the 1930s by the logical empiricists, Hume's fork asserts that all statements are exclusively either "analytic a priori" or "synthetic a posteriori," which, respectively, are universally true by mere definition or, however apparently probable, are unknowable without exact experience.

[5] By Hume's fork, sheer conceptual derivations (ostensibly, logic and mathematics), being analytic, are necessary and a priori, whereas assertions of "real existence" and traits, being synthetic, are contingent and a posteriori.

[1][4] Hume's own, simpler,[4] distinction concerned the problem of induction—that no amount of examination of cases will logically entail the conformity of unexamined cases[7]—and supported Hume's aim to position humanism on par with empirical science while combatting allegedly rampant "sophistry and illusion" by philosophers and religionists.

[1][8] Being a transcendental idealist, Kant asserted both the hope of a true metaphysics, and a literal view of Newton's law of universal gravitation by defying Hume's fork to declare the "synthetic a priori."

Immanuel Kant responded with his Transcendental Idealism in his 1781 Critique of Pure Reason, where Kant attributed to the mind a causal role in sensory experience by the mind's aligning the environmental input by arranging those sense data into the experience of space and time.

In the early 1950s, Willard Van Orman Quine undermined the analytic/synthetic division by explicating ontological relativity, as every term in any statement has its meaning contingent on a vast network of knowledge and belief, the speaker's conception of the entire world.

Into the first class fall statements such as "all bodies are extended", "all bachelors are unmarried", and ideas of mathematics and logic.

First, Hume notes that statements of the second type can never be entirely certain, due to the fallibility of our senses, the possibility of deception (see e.g. the modern brain in a vat theory) and other arguments made by philosophical skeptics.

Second, Hume claims that our belief in cause-and-effect relationships between events is not grounded on reason, but rather arises merely by habit or custom.

While some earlier philosophers (most notably Plato and Descartes) held that logical statements such as these contained the most formal reality, since they are always true and unchanging, Hume held that, while true, they contain no formal reality, because the truth of the statements rests on the definitions of the words involved, and not on actual things in the world, since there is no such thing as a true triangle or exact equality of length in the world.

If accepted, Hume's fork makes it pointless to try to prove the existence of God (for example) as a matter of fact.

Hume rejected the idea of any meaningful statement that did not fall into this schema, saying: If we take in our hand any volume; of divinity or school metaphysics, for instance; let us ask, Does it contain any abstract reasoning concerning quantity or number?