Humorism

Early texts on Indian Ayurveda medicine presented a theory of three or four humors (doṣas),[4][5] which they sometimes linked with the five elements (pañca-bhūta): earth, water, fire, air, and space.

[6] The concept of "humors" (chemical systems regulating human behaviour) became more prominent from the writing of medical theorist Alcmaeon of Croton (c. 540–500 BC).

His list of humors was longer and included fundamental elements described by Empedocles, such as water, earth, fire, air, etc.

Alcmaeon and Hippocrates posited that an extreme excess or deficiency of any of the humors (bodily fluid) in a person can be a sign of illness.

[10] Humoralism, or the doctrine of the four temperaments, as a medical theory retained its popularity for centuries, largely through the influence of the writings of Galen (129–201 AD).

As such, certain seasons and geographic areas were understood to cause imbalances in the humors, leading to varying types of disease across time and place.

For example, cities exposed to hot winds were seen as having higher rates of digestive problems as a result of excess phlegm running down from the head, while cities exposed to cold winds were associated with diseases of the lungs, acute diseases, and "hardness of the bowels", as well as ophthalmies (issues of the eyes), and nosebleeds.

[12] A fundamental idea of Hippocratic medicine was the endeavor to pinpoint the origins of illnesses in both the physiology of the human body and the influence of potentially hazardous environmental variables like air, water, and nutrition, and every humor has a distinct composition and is secreted by a different organ.

[13] Aristotle's concept of eucrasia—a state resembling equilibrium—and its relationship to the right balance of the four humors allow for the maintenance of human health, offering a more mathematical approach to medicine.

Therefore, the goal of treatment was to rid the body of some of the excess humor through techniques like purging, bloodletting, catharsis, diuresis, and others.

Bloodletting was already a prominent medical procedure by the first century, but venesection took on even more significance once Galen of Pergamum declared blood to be the most prevalent humor.

[15] The volume of blood extracted ranged from a few drops to several litres over the course of several days, depending on the patient's condition and the doctor's practice.

He believed the interactions of the humors within the body were the key to investigating the physical nature and function of the organ systems.

Galen combined his interpretation of the humors with his collection of ideas concerning nature from past philosophers in order to find conclusions about how the body works.

[19] Through this, Galen found a connection between these three parts of the soul and the three major organs that were recognized at the time: the brain, the heart, and the liver.

[22] Galen also believed that the characteristics of the soul follow the mixtures of the body, but he did not apply this idea to the Hippocratic humors.

But the nature of phlegm has no effect on the character of the soul (τοῦ δὲ φλέγµατος ἡ φύσις εἰς µὲν ἠθοποιῗαν ἄχρηστος).

These terms only partly correspond to modern medical terminology, in which there is no distinction between black and yellow bile, and phlegm has a very different meaning.

Robin Fåhræus (1921), a Swedish physician who devised the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, suggested that the four humors were based upon the observation of blood clotting in a transparent container.

[26] The French physiologist and Nobel laureate Charles Richet, when describing humorism's "phlegm or pituitary secretion" in 1910, asked rhetorically, "this strange liquid, which is the cause of tumours, of chlorosis, of rheumatism, and cacochymia – where is it?

Despite the fact that the Hippocratic physicians' therapeutic approaches have little to do with contemporary medical practice, their capacity for observation as they described the various forms of jaundice is remarkable.

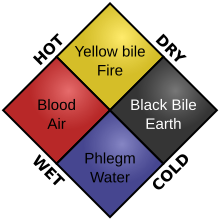

[39] The following table shows the four humors with their corresponding elements, seasons, sites of formation, and resulting temperaments:[40] Medieval medical tradition in the Golden Age of Islam adopted the theory of humorism from Greco-Roman medicine, notably via the Persian polymath Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine (1025).

[43] From Hippocrates onward, the humoral theory was adopted by Greek, Roman and Islamic physicians, and dominated the view of the human body among European physicians until at least 1543 when it was first seriously challenged by Andreas Vesalius, who mostly criticized Galen's theories of human anatomy and not the chemical hypothesis of behavioural regulation (temperament).

[45] 16th-century Swiss physician Paracelsus further developed the idea that beneficial medical substances could be found in herbs, minerals and various alchemical combinations thereof.

Specific minerals or herbs were used to treat ailments simple to complex, from an uncomplicated upper respiratory infection to the plague.

Although advances in cellular pathology and chemistry criticized humoralism by the 17th century, the theory had dominated Western medical thinking for more than 2,000 years.

One such instance occurred in the sixth and seventh centuries in the Byzantine Empire when traditional secular Greek culture gave way to Christian influences.

[48] The revival of Greek humoralism, owing in part to changing social and economic factors, did not begin until the early ninth century.

[51] Additionally, the identification of messenger molecules like hormones, growth factors, and neurotransmitters suggests that the humoral theory has not yet been made fully moribund.

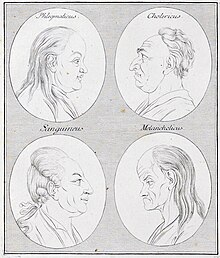

The humors were an important and popular iconographic theme in European art, found in paintings, tapestries,[52] and sets of prints.