Humpback whale

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 16,000 km (9,900 mi) each year.

Numbers have partially recovered to some 135,000 animals worldwide, but entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, and noise pollution continue to affect the species.

The humpback was first identified as baleine de la Nouvelle Angleterre by Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Regnum Animale of 1756.

In 1781, Georg Heinrich Borowski described the species, converting Brisson's name to its Latin equivalent, Balaena novaeangliae.

The genus name, Megaptera, from the Ancient Greek mega- μεγα ("giant") and ptera πτερα ("wing"),[6] refer to their large front flippers.

A 2018 genomic analysis estimated that rorquals diverged from other baleen whales in the late Miocene, between 10.5 and 7.5 million years ago.

[15] Their proportionally long pectoral fins give them great propulsion and allow them to swim in any direction, independently of the movements of the tail.

These deeper descents are believed to serve various purposes, including navigational guidance, communication with fellow humpback whales, and facilitation of feeding activities.

[12] Humpbacks have been observed to produce oral "bubble clouds" when near another individual, possibly in the context of "aggression, mate attraction, or play".

Bubble-net feeding allows whales to consume more food per mouthful while using less energy; it is particularly useful for low-density prey patches.

[41] At Stellwagen Bank off the coast of Massachusetts, humpback whales have been recorded foraging at the seafloor for sand lances.

[13] Before birth, a mother whale will move to shallower water near the coast, which reduces her chances of being harassed by escort males.

Females do not appear to approach singers that are alone, but may be drawn to gatherings of singing males, much like a lek mating system.

"Snorts" are quick, low-frequency sounds, commonly heard among animals in groups consisting of a mother–calf pair and one or more male escorts.

The suggestion is that when humpbacks suffered near-extinction during the whaling era, orcas turned to other prey but are now resuming their former practice.

The powerful flippers of humpback whales, often infested with large, sharp barnacles, are formidable weapons against orcas.

In 2020, Marine biologists Dines and Gennari et al. published a documented incident of a pair of great white sharks attacking and killing a live adult humpback whale.

[61] A second incident of a great white shark killing a humpback whale was documented off the coast of South Africa.

[65] Internal parasites of humpbacks include protozoans of the genus Entamoeba, tapeworms of the family Diphyllobothriidae, and roundworms of the infraorder Ascaridomorpha.

[67] Humpback whales are found in marine waters worldwide, except for some areas at the equator and High Arctic and some enclosed seas.

Their winter breeding grounds are located around the equator; their summer feeding areas are found in colder waters, including near the polar ice caps.

[13] In the North Atlantic, there are two separate wintering populations, one in the West Indies, from Cuba to northern Venezuela, and the other in the Cape Verde Islands and northwest Africa.

During summer, West Indies humpbacks congregate off New England, eastern Canada, and western Greenland, while the Cape Verde population gathers around Iceland and Norway.

[70] They were considered to be uncommon in the Mediterranean Sea, but increased sightings, including re-sightings, indicate that more whales may colonize or recolonize it in the future.

In contrast, Hawaiian humpbacks have a wide feeding range, but most travel to southeast Alaska and northern British Columbia.

[69] An isolated, non-migratory population feeds and breeds in the northern Indian Ocean, mainly in the Arabian Sea around Oman.

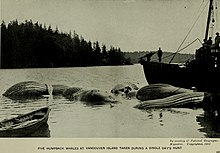

The species' highly active surface behaviors and tendency to become accustomed to boats have made them easy to observe, particularly for photographers.

[94] Humpbacks still face man-made threats, including entanglement by fishing gear, vessel collisions, human-caused noise and traffic disturbance, coastal habitat destruction, and climate change.

In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting sites, with traumatic injuries and fractures in their ears.

Virginia Beach Aquarium's stranding response coordinator, Alexander Costidis, concluded that the two causes of these unusual mortality events were vessel interactions and entanglements.