Humphry Davy

[1] According to his brother and fellow chemist John Davy, their hometown was characterised by "an almost unbounded credulity respecting the supernatural and monstrous ... Amongst the middle and higher classes, there was little taste for literature, and still less for science ...

He permitted Davy to use his laboratory and possibly directed his attention to the floodgates of the port of Hayle, which were rapidly decaying as a result of the contact between copper and iron under the influence of seawater.

[5] At this time, physician and scientific writer Thomas Beddoes and geologist John Hailstone were engaged in a geological controversy on the rival merits of the Plutonian and Neptunist hypotheses.

Davy threw himself energetically into the work of the laboratory and formed a long romantic friendship with Mrs Anna Beddoes, the novelist Maria Edgeworth's sister, who acted as his guide on walks and other fine sights of the locality.

[19] In after years Davy regretted he had ever published these immature hypotheses, which he subsequently designated "the dreams of misemployed genius which the light of experiment and observation has never conducted to truth.

[19] William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge moved to the Lake District in 1800, and asked Davy to deal with the Bristol publishers of the Lyrical Ballads, Biggs & Cottle.

[21] Wordsworth subsequently wrote to Davy on 29 July 1800, sending him the first manuscript sheet of poems and asking him specifically to correct: "any thing you find amiss in the punctuation a business at which I am ashamed to say I am no adept".

"[18] Davy revelled in his public status.Davy's lectures included spectacular and sometimes dangerous chemical demonstrations along with scientific information, and were presented with considerable showmanship by the young and handsome man.

With it, Davy created the first incandescent light by passing electric current through a thin strip of platinum, chosen because the metal had an extremely high melting point.

[30] In June 1802 Davy published in the first issue of the Journals of the Royal Institution of Great Britain his An Account of a Method of Copying Paintings upon Glass, and of Making Profiles, by the Agency of Light upon Nitrate of Silver.

At the beginning of June, Davy received a letter from the Swedish chemist Berzelius claiming that he, in conjunction with Dr. Pontin, had successfully obtained amalgams of calcium and barium by electrolysing lime and barytes using a mercury cathode.

[34] He noted that while these amalgams oxidised in only a few minutes when exposed to air they could be preserved for lengthy periods of time when submerged in naphtha before becoming covered with a white crust.

[35] On 30 June 1808 Davy reported to the Royal Society that he had successfully isolated four new metals which he named barium, calcium, strontium and magnium (later changed to magnesium) which were subsequently published in the Philosophical Transactions.

"[38] Chlorine was discovered in 1774 by Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele, who called it "dephlogisticated marine acid" (see phlogiston theory) and mistakenly thought it contained oxygen.

[41] In October 1813, he and his wife, accompanied by Michael Faraday as his scientific assistant (also treated as a valet), travelled to France to collect the second edition of the prix du Galvanisme, a medal that Napoleon Bonaparte had awarded Davy for his electro-chemical work.

Faraday noted "Tis indeed a strange venture at this time, to trust ourselves in a foreign and hostile country, where so little regard is had to protestations of honour, that the slightest suspicion would be sufficient to separate us for ever from England, and perhaps from life".

[43] While in Paris, Davy attended lectures at the Ecole Polytechnique, including those by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac on a mysterious substance isolated by Bernard Courtois.

[46] They sojourned in Florence, where using the burning glass of the Grand Duke of Tuscany [47] in a series of experiments conducted with Faraday's assistance, Davy succeeded in using the sun's rays to ignite diamond, proving it is composed of pure carbon.

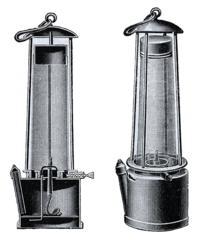

To take back from her by contributions the wealth she has acquired by them to suffer her to retain nothing that the republican or imperial armies have stolen: This last duty is demanded no less by policy than justice.After his return to England in 1815, Davy began experimenting with lamps that could be used safely in coal mines.

The Revd Dr Robert Gray of Bishopwearmouth in Sunderland, founder of the Society for Preventing Accidents in Coalmines, had written to Davy suggesting that he might use his 'extensive stores of chemical knowledge' to address the issue of mining explosions caused by firedamp, or methane mixed with oxygen, which was often ignited by the open flames of the lamps then used by miners.

Incidents such as the Felling mine disaster of 1812 near Newcastle, in which 92 men were killed, not only caused great loss of life among miners but also meant that their widows and children had to be supported by the public purse.

Although the idea of the safety lamp had already been demonstrated by William Reid Clanny and by the then unknown (but later very famous) engineer George Stephenson, Davy's use of wire gauze to prevent the spread of flame was used by many other inventors in their later designs.

[55] Initial experiments were again promising and his work resulted in 'partially unrolling 23 MSS., from which fragments of writing were obtained' [56] but after returning to Naples on 1 December 1819 from a summer in the Alps, Davy complained that 'the Italians at the museum [were] no longer helpful but obstructive'.

The Society was in transition from a club for gentlemen interested in natural philosophy, connected with the political and social elite, to an academy representing increasingly specialised sciences.

The strongest alternative had been William Hyde Wollaston, who was supported by the "Cambridge Network" of outstanding mathematicians such as Charles Babbage and John Herschel, who tried to block Davy.

They were aware that Davy supported some modernisation, but thought that he would not sufficiently encourage aspiring young mathematicians, astronomers and geologists, who were beginning to form specialist societies.

In spite of his ungainly exterior and peculiar manner, his happy gifts of exposition and illustration won him extraordinary popularity as a lecturer, his experiments were ingenious and rapidly performed, and Coleridge went to hear him "to increase his stock of metaphors."

The dominating ambition of his life was to achieve fame; occasional petty jealousy did not diminish his concern for the "cause of humanity", to use a phrase often employed by him in connection with his invention of the miners' lamp.

[69] Davy spent the last months of his life writing Consolations in Travel, an immensely popular, somewhat freeform compendium of poetry, thoughts on science and philosophy.

After spending many months attempting to recuperate, Davy died in a room at L'Hotel de la Couronne, in the Rue du Rhone, in Geneva, Switzerland, on 29 May 1829.