Voltaic pile

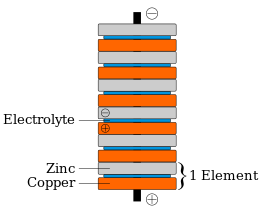

In 1800, Volta stacked several pairs of alternating copper (or silver) and zinc discs (electrodes) separated by cloth or cardboard soaked in brine, which increased the total electromotive force.

[10] On 20 March 1800, Alessandro Volta wrote to the London Royal Society to describe the technique for producing electric current using his device.

Humphry Davy showed that the electromotive force, which drives the electric current through a circuit containing a single voltaic cell, was caused by a chemical reaction, not by the voltage difference between the two metals.

[12] Davy used a 2000-pair pile made for the Royal Institution in 1808 to demonstrate carbon arc discharge[13] and isolate five new elements: barium, calcium, boron, strontium and magnesium.

His work to prove this theory led him to propose two laws of electrochemistry which stood in direct conflict with the current scientific beliefs of the day as laid down by Volta thirty years earlier.

However, chemists soon realized that water in the electrolyte was involved in the pile's chemical reactions, and led to the evolution of hydrogen gas from the copper or silver electrode.

Copper does act as a catalyst for the hydrogen-evolution reaction, which otherwise could occur equally well directly at the zinc electrode without current flow through the external circuit.

The copper electrode could be replaced in the system by any sufficiently noble/inert and catalytically active metallic conductor (Ag, Pt, stainless steel, graphite, ...).

The global reaction can be written as follows: This is usefully stylized by means of the electro-chemical chain notation: in which a vertical bar each time represents an interface.

Francis Ronalds in 1814 was one of the first to realize that dry piles also worked through chemical reaction rather than metal-to-metal contact, even though corrosion was not visible due to the very small currents generated.